Alexander George Edwin Smith, Cayuga contractor, soldier, war hero (born 14 August 1879 on the Six Nations Grand River Reserve, ON; died 21 August 1954 in Buffalo, New York), was a veteran of the First World War. He served as an officer in the pre-war Militia, was commissioned as an infantry lieutenant in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and received the Military Cross (MC) for his heroic actions on the Western Front.

Alexander Smith, c. 1916

Early Life

Smith was the oldest son of Six Nations Cayuga Chief Alexander George Smith. Prior to the First World War, he served in the 37th Haldimand Rifles, a unit with many Indigenous soldiers in its ranks. He served in the battalion for about 18 years and rose to the rank of captain.

First World War

Smith enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) on 26 October 1914 in the 20th Battalion. Despite his Militia captain’s rank, he joined as a lieutenant, although he was later promoted to captain. Smith sailed to Britain on 15 May 1915 and, after a further period of training, was sent to France.

Smith arrived in France on 14 September 1915 with the 20th (Central Ontario) Battalion, a unit in 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division. He was only in France until November however, when he was sent back to Britain due to deafness caused by high explosive shells. He remained there for treatment and recuperation until June 1916, when he returned to France.

The Battle of the Somme

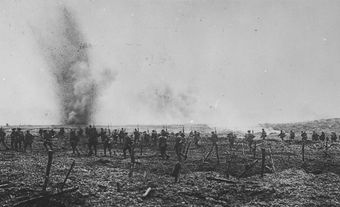

The infamous Battle of the Somme began on 1 July 1916 and became one of the greatest bloodbaths in history. In August, with the attack faltering, General Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief, called on the Canadian Corps, then consisting of three divisions stationed in the Ypres area of Belgium.

The Canadians launched their first attack on 15 September, when 2nd and 3rd Divisions advanced against various objectives along with nine British divisions. This phase of the attack ended on 22 September, with considerable advances made by the Canadians. After a four-day pause, the Canadians resumed their attack on 26 September following three days of preliminary bombardment.

Military Cross

The next day, on 27 September 1916, Smith led his company in an attack in support of the 8th (90th Winnipeg Rifles) Battalion. He went ahead with a small group of bombers (grenade-throwers) and captured an enemy trench and 50 prisoners. Smith was awarded the prestigious Military Cross (MC) for actions that day, “displaying the greatest courage throughout,” as his citation noted. Although he was buried by shellfire twice during the attack, “he stuck to his post.”

In a letter to his father shortly afterward, Smith asked him to tell his wife, Mabel, that he received the MC for “bravery and gallantry on the field of the greatest battle the world has ever known.” He went on to note that he wished his mother were still alive (she had died in January) “so she could have enjoyed the thought, that put to the test, I, her son, proved my metal [mettle] and no coward.”

In closing, Smith alluded to both his loneliness and faith in the future: “Please write me often as I’m so lonely here. Give my love to all at home. Bear yet a little longer. God in His great mercy will bring us together again in due time.”

Later War Service

Smith suffered from “shell shock” (as post-traumatic stress disorder was then called) after being buried alive during the action that earned him the Military Cross. As a result, he returned to Britain later in September. He remained there until April 1917 before sailing for Canada.

Back home, he continued to serve the war effort at the Niagara-on-the-Lake training camp, where he was adjutant of the 1st Depot Battalion until July 1918. Among the trainees were some 23,000 Polish-born soldiers, recruited from across Canada and the United States and destined for the French army. Smith was awarded the Order of the Black Star (Officer class) in the name of the President of France for this work, one of only five Canadians to receive this prestigious French colonial decoration.

Post-War Life

After the war, Alexander Smith followed in his father’s footsteps and became chief of the Cayuga. Unfortunately, his wartime injuries left him with permanent disabilities: hearing impairment, severe headaches and occasional neck pain. The Pension Board awarded him $25 a month and another $24 for his wife and children. Despite being a war hero, Smith was legally a ward of the state and the Department of Indian Affairs controlled his pension (see Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs).

In 1932, Smith was diagnosed with asthma, a result of injuries suffered during the war. He was unable to sleep for several nights each week and could not work for several years. By 1939, he had recovered enough to farm 100 acres with the help of his sons and nephews. This was short-lived however, and his asthma forced him to move to Buffalo, New York, with his family in 1942. In 1945, he received treatment in Toronto for his ailments. However, he could not return to his farm on the reserve as he had hoped and went back to Buffalo to spend his last years.

One of Smith’s sons, Harold, was a well-known actor. Under the name Jay Silverheels, he appeared in films and on television. He is best known for portraying Tonto, the faithful companion of the Lone Ranger in the long-running (1949–1957) western TV series.

Legacy

Alexander Smith was one of the most highly decorated Indigenous soldiers of the First World War. He won the Military Cross for heroic actions at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and the Order of the Black Star from France. After his death from a heart attack, Smith’s remains were repatriated to Canada for burial at Saint Paul’s Anglican Church Cemetery in the Tuscarora Township on the Six Nations Grand River Reserve.

Did You Know?

Charles Denton Smith, Alexander Smith’s brother, was also a decorated Cayuga soldier of the First World War. A carpenter by trade, Charles was born on 2 October 1883 on the Six Nations Grand River Reserve (ON). Before the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Charles served in the 37th Haldimand Rifles for 10 years and rose to the rank of lieutenant. He enrolled in the 20th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) on 13 November 1914 and was commissioned as a lieutenant. He resigned his commission in April 1915, but re-enrolled in November, this time in the 114th (Brock’s Rangers) Battalion. Charles was promoted captain on 1 October 1916 and sailed to Britain at the end of the month. The 114th Battalion was broken up on arrival for reinforcements and Smith served in several different units. He reverted to lieutenant in August 1917, an action usually taken to receive a posting at the Western Front. He was sent to France to the 18th (Western Ontario) Battalion in the same brigade and division as his brother in mid-August 1917. Charles was awarded the Military Cross for his heroic actions in the Belgian village of Frameries on 9 November 1918 ― only two days before the Armistice (see Remembrance Day in Canada). The citation noted, “He led his platoon forward with such rapidity that he surprised a party of sappers [engineers], preparing to blow up a road mine. Rushing forward, he shot the man who was in the act of igniting the fuse. The same evening, he personally captured a machine gun, disposing of the crew.” Charles returned to Canada on 7 May 1919 and was demobilized 10 days later. He received his MC from the Prince of Wales in October 1919 during the Prince’s Royal Tour of Canada. Charles Smith died in June 1960.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom