John Anderson killed a man in self-defence in the United States while escaping from slavery in 1853. Several years after arriving in Canada, he was threatened with extradition to stand trial for murder in the United States. International agreements made this the law even though Anderson’s chances of getting a fair trial were non-existent. Canadian public opinion opposed the extradition and a protest movement developed in support of Anderson. A Canadian court stopped the extradition while a parallel legal challenge in London led to important changes which shaped Canada’s independent judicial system.

Definition

Extradition - Extradition is a legal process by which someone who has committed a crime, or is suspected to have committed a crime, is handed from one country, province or territory to another.

Background

John Anderson was born into slavery in Missouri in the early 1830s. He was originally named Jack Burton. He and his family were enslaved by Moses Burton, a tobacco farmer. When Anderson was a boy, his mother was sold. John’s father had fled his enslavement and is believed to have made his way to South America.

Anderson married in 1850 and started a family with an enslaved woman who lived several kilometres away. In 1853, Anderson was sold and separated from his family. He decided to escape to freedom after he was denied a travel pass to walk more than 50 kilometres to visit his family.

Escape

Anderson escaped on an early Sunday morning in late September 1853 and visited his wife, infant child and father-in-law. He told them that he was determined to reach freedom in Canada. Three days later, he passed by the farm of Seneca Digges. At the time, any enslaved person found more than 32 kilometres from his home without a pass could be seized and returned for a reward. Anderson admitted to Digges that he didn’t have a pass but insisted that he had legitimate business. When Digges insisted that Anderson accompany him back to his house for dinner, Anderson refused and ran. Digges pursued Anderson with his own enslaved men, telling them they would receive a reward for Anderson’s capture. As Anderson would later relate, the pursuit lasted several hours before he was cornered by Digges. Fearing for his life, Anderson stabbed Digges with his knife and convinced the others to go home. Exhausted, Anderson returned to his wife’s house. She encouraged him to continue his flight to Canada. Digges died of his wounds two weeks later.

Anderson continued his journey to Illinois and Michigan, which were free states, crossing from Detroit into Windsor, Ontario, in early November 1853. Anderson travelled mostly at night to avoid detection by bounty hunters. Sympathetic farmers and abolitionist societies assisted him along the way.

Life in Canada

Soon after his arrival in Canada, John Anderson took a job with the Great Western Railway, working on the section between Windsor and Chatham, Ontario. Between 1854 and 1860 Anderson moved several times and took different names to avoid detection, since he was worried about bounty hunters who might be pursuing him. Along the way, he learned to become a mason and plasterer, and by 1860 he had bought a house near Caledonia.

Arrest and Attempted Extradition

In early 1860, Anderson told a friend named Wynne the truth about his escape and the death of Digges. Anderson was later betrayed by his friend, who told the story to the local justice of the peace, who then had Anderson arrested. However, Anderson was soon released because there was no evidence or witnesses to support the story. Eventually, though, a police detective and slavecatcher from Detroit named Gunning produced witnesses, including Digges’s sons, and alleged that John Anderson had killed Digges deliberately and maliciously rather than in self-defence. Anderson was again arrested and brought to the Brantford jail on 28 September 1860.

Within four days of the arrest, the American secretary of state appealed to the British government for Anderson’s return to Missouri to stand trial for murder. Crucially, the extradition request did not list Anderson as a formerly enslaved person but instead simply as a “man of colour.” This was an important distinction, since the British government originally thought Anderson was a free man who had committed murder, not an enslaved man who had killed the person trying to capture him.

Legal Arguments and Public Support

Anderson’s lawyer, S.B. Freeman, appealed the extradition order to the Court of Queen’s Bench. Chief Justice Sir John Beverly Robinson called upon John Anderson to appear at Osgoode Hall on 24 November 1860.

Since enslaved Blacks were considered property, American slave owners occasionally made formal requests to the British government to have their property returned. However, slave-trading, and later slave-owning, became illegal in British North America in the early 19th century. Thus, enslaved people generally became free as soon as they reached Canada. This in turn led American slave-owners to lay charges against their former slaves for “stealing” the clothes they wore or the chains that bound them.

While the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 had sought to clarify legal matters between Britain and the United States, it stated that extraditions would occur only if the crime committed in one country was recognized as a crime in the other. Since slavery was illegal in Canada but legal in some American states, minor offences committed by escaping slaves were not considered crimes because they were committed in an attempt to gain freedom. In the extradition request, Anderson was not listed as an enslaved person, but rather as a person of colour, and the courts assumed this meant he had committed murder as a free man. As such, it was argued that under the treaty Anderson could be returned to Missouri to stand trial for murder.

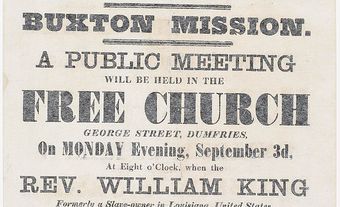

By this time, the Anderson case had become a national sensation in Canada. Public meetings were organized in cities large and small. Public opinion was overwhelmingly in support of Anderson and against extradition, supported by newspapers nationwide that vigorously opposed slavery. It was generally understood at the time that a Black man charged with murdering a white man in the United States could not possibly hope to get a fair trial. The fact that Anderson was formerly enslaved made it all the worse. Extradition, in this case, was a de facto death sentence. Popular opinion was so strongly opposed to Anderson’s extradition that additional police forces were ordered in, since justices feared a mob of protesters would break Anderson out of jail.

Extradition Case and Appeal

The three justices of the Court of Queen’s Bench ruled to extradite John Anderson in a 2–1 split decision on 15 December 1860. Though the judges all claimed to personally detest slavery, two of the three interpreted the Webster-Ashburton Treaty literally. The dissenting voice, that of Justice McLean, argued that the desire to be free was a natural condition for all people, and it was only reasonable for an enslaved person to do anything and everything they could to free themselves.

However, there was widespread support for an appeal. Canadian abolitionists, working with their British counterparts, successfully appealed the decision before the British Court of Queen’s Bench at Westminster, which ordered Anderson released on 14 January 1861. In doing so, the British court overruled Canada’s colonial court system. This was a controversial decision on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Even though it benefitted John Anderson, it was also seen as a step backwards for Canada’s justice system, which had been making incremental steps toward greater autonomy.

However, the decision of the British court wouldn’t matter for Anderson, since his counsel had already appealed the verdict to the Court of Common Pleas in Toronto. Anderson’s lawyers argued two technicalities that would ultimately secure Anderson’s freedom. First, that the crime wasn’t murder, but manslaughter — a crime not covered by the Webster-Ashburton treaty. Second, that the authorities in Brantford had no jurisdiction, since no court in Missouri had ever formally charged Anderson with murder.

Aftermath

Anderson was released on 16 February 1861. People in Toronto and in other cities across Canada celebrated in the streets. In the days and weeks following his release, Anderson gave public speeches and visited supporters in Canada West and Canada East. Subsequently, the governments of Canada West and Britain updated their laws to ensure a similar situation could not be repeated: Britain passed a law in 1862 that limited its ability to interfere in the judiciary of its colonies, and Canada West made extradition cases the responsibility of superior courts in 1861.

In spring 1861, John Anderson travelled to the United Kingdom, where he delivered many speeches in support of abolition. He related his life story to Harper Twelvetrees, a British industrialist and antislavery campaigner, who published The Story of the Life of John Anderson, the Fugitive Slave in 1863.

On Christmas Eve 1862, Anderson left Liverpool for Liberia. There are no known records of his life after that point.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom