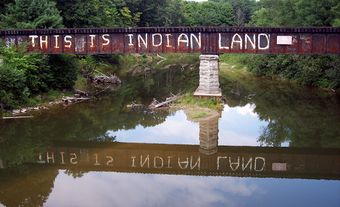

In September 1850, the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) of the Upper Great Lakes signed two separate but interconnected treaties: the Robinson-Superior Treaty (RST) and Robinson-Huron Treaty (RHT). These agreements provided the Province of Canada (Canada East and Canada West, the future Quebec and Ontario) access to the north shores of Lake Huron and Lake Superior for settlement and mineral extraction. In exchange, the Indigenous peoples in the region gained recognition of hunting and fishing rights, an annuity (annual payment), and a reservation from the surrender of specific lands for each signatory community. Interpretation of the Robinson treaties have had a legal and socioeconomic impact on Indigenous and settler communities, and they established precedents for the subsequent Numbered Treaties.

Historical Context

Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) demands and the need for a treaty began in the 1840s with the discovery of copper and iron deposits on Lake Superior’s south shore. Speculation about the north shore’s potential also increased the desire for a treaty. As a result, a Crown Lands and Customs Agent, Joseph Wilson, was appointed to Sault Ste. Marie (now in Ontario). Shortly after his 1843 arrival, Chief Shingwaukonse informed Wilson about Anishinaabeg claims and rights. The Province of Canada then claimed authority over Lake Huron and Lake Superior’s north shores in 1845 before issuing the first mining lease. By 1846, despite the lack of a treaty, 64 mineral licenses had been issued and the surveying of the north shore had begun.

While surveying Sault Ste. Marie’s town plot in 1846, government surveyor Alexander Vidal was confronted by Nebenaigoching and Shingwaukonse. Shingwaukonse demanded Vidal stop surveying until a treaty was negotiated. Mining speculator and publisher George Desbarats, who held interests on the north shore of Lake Huron, wrote to the superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1847 requesting Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) claims be resolved. Chiefs Shingwaukonse, Nebenaigoching, and Menissinowenninne then visited Governor General Lord Elgin in Montreal in 1849. Their address to the governor general was printed on 7 July 1849 in the Montreal Gazette. It revealed that the Anishinaabeg had requested justice and a treaty while challenging British claims of treating Indigenous peoples with greater dignity and justice than the Americans. The Anishinaabeg also accused the British of stealing their lands.

As a result of the 1849 visit, Vidal and Captain T. G. Anderson, a veteran of the War of 1812 and superintendent of Indian Affairs, were appointed to investigate Anishinaabeg claims. Vidal and Anderson began on 24 September in Fort William and reached Sault Ste Marie by 13 October. Due to the lateness of the season, the commissioners failed to speak with many Anishinaabeg. Many bands had moved inland for the winter or were avoiding white settlers to escape cholera.

The 15–17 October meetings at the Sault saw the Anishinaabeg restate their claims with the assistance of their lawyer, Allan Macdonell. The commissioners refused to negotiate or speak with the lawyer. According to Macdonell, before storming out of the meeting Vidal threatened that there would be no treaty if the Anishinaabeg refused to negotiate directly with the government. The commissioners left the Sault for Penetanguishene, where they met with more assembled chiefs on 3 November before departing to write their reports (completed in Toronto in December 1849).

Angered by the investigators’ behaviour and government inaction, the Anishinaabeg seized the Montreal Mining company site at Pointe-aux-Mines at Mica Bay, Lake Superior, in early November 1849. This led to the evacuation of the mine and rumours of an impending “Indian war.” In response, the government dispatched troops, who arrived at the Sault on 2 December (see Mica Bay Incident). The individuals deemed responsible for the attack — Shingwaukonse, Nebenaigoching, and their allies Wharton Metcalfe and Allan Macdonell — were arrested and transported to Toronto. Shingwaukonse and Nebenaigoching returned home in early 1850 to await the trial. Their charges were eventually stayed (thrown out) in 1851 along with those against Macdonell, while Metcalfe escaped.

Negotiations

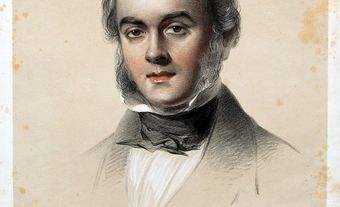

These events forced the government of Canada West to negotiate a treaty. On 11 January 1850, William Benjamin Robinson, a former mine manager and the chief justice’s brother, was appointed treaty commissioner. Robinson arrived in the Sault on 18 August 1850 and was joined by Governor General Lord Elgin on 30 August. After informing the chiefs that Robinson held the Queen’s full confidence and would negotiate a fair treaty, Elgin departed. Present throughout the negotiations and signing were troops sent to quell the “Indian uprising.” Formal negotiations took place for several days in early September and concluded on 9 September.

The chiefs from Lake Huron, led by Shingwaukonse, were familiar with the terms of past Upper Canada and American treaties and demanded an annuity of $10 per head and large reserves. Robinson rejected these “extravagant terms” and decided that two treaties were necessary. He believed that the four chiefs and five principal men from Lake Superior, who were less affected by colonial intrusions, were more willing to sign. Robinson drew up a treaty on 6 September, which was signed the following day. Robinson then informed Shingwaukonse that he would prepare a treaty for the Lake Huron chiefs. He also threatened that those who did not sign would receive no protection or compensation. The chiefs were given two days to consider their options. Shingwaukonse restated his demands and asked for large land grants for the Métis, but Robinson refused to budge. The Lake Huron treaty was then signed.

Treaty Terms

Both the Robinson-Superior Treaty (RST) and Robinson-Huron Treaty (RHT) contained a schedule of reserves, hunting and fishing rights that lasted until the lands were taken up for settlement or development, a one-time payment of £2000, and an annum (annual payment or annuity) of £500 and £600, respectively. Both treaties also contained an “escalator clause” for the annuity, which meant that the Crown would increase the annuity as revenues from the lands increased.

Under these terms the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) surrendered the north shore of Lake Superior from “Batchewana Bay to Pigeon River, at the western extremity of said Lake, and inland throughout that extent to the height of land.” They also surrendered the north shore of Lake Huron “from Penetanguishine to Sault Ste. Maire, and thence to Batchewanaung Bay, on the Northern Shore of Lake Superior; together with the Islands in the said Lakes, opposite to the Shores thereof, and inland to the Height of land.”

Legacy

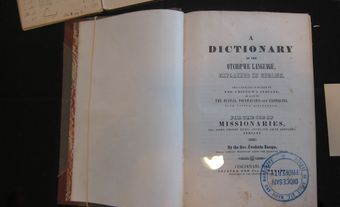

The Robinson Treaties used American precedents which established a pattern for future treaty negotiation and pageantry in Canada (see Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada). The presence of British troops at the signing as well as the visit by the governor general was adapted and expanded for the Numbered Treaties (1871–1921). The idea of an annuity (annual payment) and the continuance of hunting and fishing rights on Crown lands were also drawn from American precedents and applied to post-Confederation treaties.

Robinson’s promise that Métis claims would be dealt with were never fulfilled. After many court challenges, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized Métis hunting rights in the 2003 Powley Case.

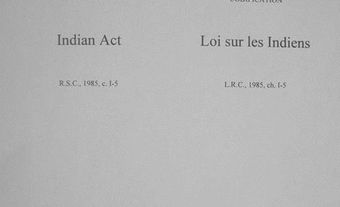

Land loss continued throughout the 19th and 20th century. Anishinaabeg signatories did not realize the potential economic benefits of resource extraction. Implementation of the Indian Act in 1876 and the 1924 Indian Lands Act reduced the treaties’ effectiveness, which negatively affected Anishinaabeg livelihoods.

The annuity escalator clause contained within the treaties was activated in 1874 when payments increased to $4 per person. The failure to increase the annuity since 1874 has led to a 2019 court claim. Treaty signatories were seeking an annuity increase and retroactive compensation from the government for failing to raise the annuity. In 2023, 21 First Nations signed a proposed settlement with Canada and Ontario worth a total of $10 billion to compensate for annuities under the Robinson-Huron Treaty. As of September 2023, First Nations from the Robinson-Superior Treaty territory are continuing through the court system to determine compensation. The judge for the Robinson-Superior Treaty court case is also responsible for determining how the treaty should be fulfilled into the future.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom