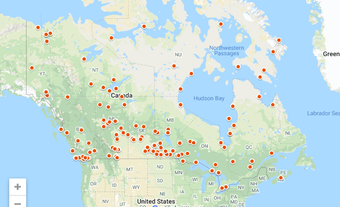

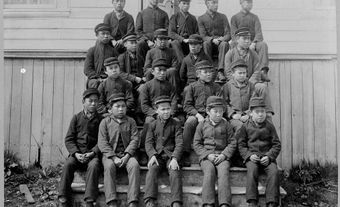

Historical trauma occurs when trauma caused by historical oppression is passed down through generations. For more than 100 years, the Canadian government supported residential school programs that isolated Indigenous children from their families and communities (see Residential Schools in Canada). Under the guise of educating and preparing Indigenous children for their participation in Canadian society, the federal government and other administrators of the residential school system committed what has since been described as an act of cultural genocide. As generations of students left these institutions, they returned to their home communities without the knowledge, skills or tools to cope in either world. The impacts of their institutionalization in residential school continue to be felt by subsequent generations. This is called intergenerational trauma.

This is the full-length entry about Intergenerational Trauma and Residential Schools. For a plain-language summary, please see Intergenerational Trauma and Residential Schools (Plain-Language Summary).

History

The study of intergenerational trauma, which researchers also call “transgenerational trauma,” is a developing field. The phenomenon is often examined as part of research into historical trauma. Preliminary studies have focused on Holocaust Survivors and their offspring (see Canada and the Holocaust). In 1966, Canadian psychiatrist Dr. Vivian M. Rakoff wrote one of the first articles on the topic. His paper focused on family dynamics, particularly between parent and child (see Family Studies). Subsequent studies described high rates of psychological distress among children of Holocaust Survivors. Some noted their specific behaviour patterns, including being overly protective of their parents, needing a high level of control, exhibiting an obsession with the Holocaust and having immature dependency.

As early as the 2010s, researchers began examining the intergenerational effects of the residential school system on Indigenous people and communities across Canada.

From Individual Trauma to Intergenerational Trauma

Many children experienced psychological, spiritual, physical and sexual abuse at the hands of their so-called caregivers in the residential school system (see Child Abuse). On an individual level, the long-term impact of residential school experiences has left many former students facing significant psychological challenges (see Mental Health). These range from heightened feelings of anger, anxiety, low self-esteem and depression to post-traumatic stress disorder and high rates of suicide, among other things. In a national survey conducted between 2008 and 2010, members of First Nations communities identified managing substance use as the number-one challenge for community wellness (see Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

Residential schools included parenting models based on punishment, abuse, coercion and control. With little experience of nurturing family environments from which to draw, generations of residential school Survivors struggle with residual trauma. As adults, many are ill-prepared to nurture their own children. The effects of these chaotic family systems can be seen in the high rates of family violence and domestic partner abuse. While Indigenous children represent less than 8 per cent of children under 14 years of age in Canada, they make up nearly 54 per cent of children in the care of child welfare authorities.

In her 1991 work, Impact of Residential Schools and Other Root Causes of Poor Mental Health, Maggie Hodgson summarizes the cumulative impact of the loss of parenting knowledge and skills across generations:

If you subject one generation to that kind of parenting and they become adults and have children; those children become subjected to that treatment and then you subject a third generation to a residential school system the same as the first two generations. You have a whole society affected by isolation, loneliness, sadness, anger, hopelessness and pain.

High levels of Indigenous unemployment, a disproportionate number of Indigenous people involved in the justice system, high rates of Indigenous homelessness in urban centres and poor housing conditions in many First Nations communities all share a root cause: Canada’s residential school policy.

Transmission of Intergenerational Trauma

Psychological and sociological researchers are exploring theories about how trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next. They are trying to understand the persistent nature of trauma-induced symptoms that continue to affect the well-being of many Indigenous individuals, their families and their communities.

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart first documented the impact of historic loss in her study of grief as experienced by the Lakota community (see Dakota) in the late 1990s. More recent scholars have offered theories on the origins of the trauma among Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Sociocultural Model

Researchers have many working theories on how intergenerational trauma is transmitted. One can be thought of as the sociocultural model, which focuses on parenting styles and how environmental factors influence child development. This model assumes that children learn from their immediate environment and from the people who directly contribute to their development, such as their parents and immediate family members. When children experience abuse, neglect and stress in their home environments, they are unable to develop appropriate coping skills or strategies to deal with future life stressors. In some communities, multiple families lack the knowledge and skills to support their children’s emotional and psychological well-being. Researchers believe that when this is the case, it becomes more difficult to redress behaviours that have become the community norm. Negative parenting behaviours are replicated by the next generation, and the cycle of trauma renews. Particularly when geographic isolation and social marginalization limits access to new, external parenting models, that cycle remains unaffected and can impact subsequent generations of children.

Psychological Model

Another theory could be described as the psychological model of intergenerational transmission. It focuses on the importance of a parent’s attachment to their child. Their ability to tune into the needs of their child is critical to the child’s development of self-regulation. Early infant brain development can be affected if a child’s needs are not attended to in a way that helps them develop a sense of security and trust in their immediate environment. Cognitive delays and negative coping strategies could follow, impacting a child’s success in school and other social settings, as well as later in life. Whole communities can be affected if this attachment is disrupted for groups of related individuals, and the cycle of psychological trauma could continue to be perpetrated across generations.

Physiological Model

Physiological theories focus on predisposed genetic or biological factors to explain the transmission of trauma across generations. Some recent theories propose that biological risk factors can include “toxic stress” caused by a child’s environment. This type of problem can contribute to actual changes in the child’s brain development due to abnormal levels of cortisol, dopamine or serotonin, which can affect a child’s future ability to process stressful conditions. This leads to heightened activity levels and can have an effect on concentration and learning abilities (see Specific Learning Disabilities). Children dealing with such conditions are described as having limited abilities to self-soothe or regulate their behaviours while under stress. There are also epigenetic theories that suggest maternal stress can impact a child’s in-utero development, ultimately affecting the function of their genes. According to these theories, genetic conditions can predispose an individual’s negative response to stress, and these conditions can be passed on to future generations.

Treatment

These sociocultural, psychological and physiological theories consider historical trauma as a person's expression of traumatic experiences. They are linked to their distinct ancestral experience. Interventions to treat PTSD have focused on developing health and social programs that address a person's symptoms. But the effectiveness of these programs in the treatment of intergenerational trauma has yet to be determined.

Many researchers are now looking to isolate external conditions that foster trauma among specific populations. They are focusing on groups who have been historically marginalized economically, politically and socially by mainstream or dominant culture (see Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada). A recent research article examined the effects of traumatic events and perceived discrimination on the mental well-being of four historically marginalized groups in Canada: Indigenous people, Black people, Jewish people and women. Researchers found that any type of intervention that doesn’t consider the cultural and social contexts in which these groups live risks contributing to their oppression (see Social History). This moves the discussion away from victim blaming to one that leverages community knowledge and experiences in new ways.

Moving Forward

Most theories focus on the sociocultural, psychological and physiological ways that trauma is transmitted between generations. Others examine external factors, including racism, cultural discrimination and economic marginalization (see Economic Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada). The latter theories describe the role society plays in perpetuating the intergenerational effects of the residential school experience — something that researchers say must be acknowledged in order to break the cycles of trauma.

Strategies for moving forward with empowerment strategies include increased self-government and self-determination (see Indigenous Self-Government in Canada). The 2008 apology issued by the Canadian government to Survivors of federally run residential schools was a start, but the task of identifying strategies for disrupting the legacy of the residential school system remains.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom