The 1969 White Paper (formally known as the “Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, 1969”) was a Canadian government policy paper that attempted to abolish previous legal documents relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada, including the Indian Act and treaties. It also aimed to assimilate all “Indian” peoples under the Canadian state. The 1969 White Paper was proposed by Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Jean Chrétien and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau to widespread criticism. The policy proposed to eliminate Indian Status, incorporate First Nations under provincial government responsibilities, and impose land decisions, notions of private property and economic agendas on Indigenous communities. The backlash to the 1969 White Paper was monumental, leading not only to its withdrawal in 1970, but to a wave of activism, academic work and court decisions over the next five decades. (See also Indigenous Political Organization and Activism in Canada and Indigenous Peoples in Canadian Law.)

What is the 1969 White Paper?

The 1969 White Paper (formally known as the “Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, 1969”) was a Canadian policy paper presented to Parliament by Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Jean Chrétien and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. The policy was intended to abolish previous legal documents relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada (specifically, the Indian Act.) It also aimed to eliminate treaties and assimilate all “Indians” fully into the Canadian state.

Contextual Information

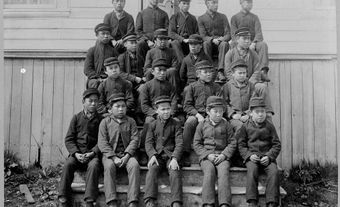

By the 1960s, the impact of European settlement had disastrous effects on Indigenous populations throughout Canada. Many communities had been reduced by as much as 90 per cent due to rampant disease, interruptions to trade and food routes, war and industrialization. These, combined with a series of oppressive policies such as the 1876 Indian Act and residential schools, had driven Indigenous peoples into poverty, strife and alarming death rates. (See also Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) Meanwhile, the Government of Canada had promised, via treaties and other legal documents, to recognize First Nations’ sovereignty and land title and claims.

Alongside a growing civil rights movement and the tremendous impact made by Indigenous soldiers in the First and Second World Wars, Canadians began to openly question the longstanding and institutional mistreatment and discrimination toward Indigenous peoples. (See also Indigenous Peoples in the World Wars and Racial Segregation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) In 1963, anthropologist Harry B. Hawthorn was commissioned by the federal government to investigate some of the social conditions surrounding Indigenous peoples in Canada. Hawthorn’s report, A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies, labelled Indigenous peoples “citizens minus” – the most marginalized and disadvantaged population in Canada.

In response to Hawthorn’s report, in 1968, the Trudeau government began a series of consultations with Indigenous leaders on a new direction. At these meetings, Indigenous leaders expressed concerns to the government that treaty and special rights had never been recognized nor delivered, historical grievances had emerged or had never been addressed (especially in the case of land claims) and Indigenous peoples were neglected in Canadian policy making.

Contents of the 1969 White Paper

Presenting the White Paper in 1969, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Jean Chrétien and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau proposed to deal with Indigenous issues definitively. The paper indicated that policies relating to First Nations were exclusionary and discriminatory, as they did not apply to Canadians in general. Trudeau and Chrétien’s White Paper proposed to eliminate “Indian” as a distinct legal status – therefore making First Nations “equal” to other Canadians.

They also proposed to dismantle the Department of Indian Affairs within five years, repeal the Indian Act, and eliminate all treaties between First Nations and Canada. The White Paper would convert reserve lands to private property owned by the band or its members and transfer all responsibility for services to provincial governments. It also proposed to appoint a commissioner to settle all land claims and provide funds for economic development. At the same time, Chrétien and Trudeau saw the White Paper as a way of eliminating the rising cost of administering Indian Affairs and treaty responsibilities.

Responses to the 1969 White Paper

The backlash to the 1969 White Paper was monumental. Major opposition emerged from several organizations, including the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations) and its provincial chapters. Many felt the document overlooked concerns raised during consultations and appeared to be a final attempt to assimilate Indigenous peoples into the Canadian population. Leaders felt that instead of dealing with First Nations fairly and appropriately, the federal government was absolving itself of historical promises and responsibilities. Instead, provinces – with whom First Nations had no relationship – would be forced to deal with longstanding issues.

An important figure in this response was Harold Cardinal, a Cree leader of the Indian Association of Alberta (IAA). In 1970, Cardinal and the IAA rejected the White Paper by publishing the document Citizens Plus, which became known as the Red Paper. The Red Paper strongly defended treaty rights and Indigenous rights to lands, public services and self-determination. Indigenous leaders including Cardinal as well as John Snow and Adam Soloway, met with the Liberal Cabinet in Parliament to present the Red Paper.

Another major response to the White Paper came from within British Columbia. In November 1969, a conference hosted over 140 bands and resulted in the development of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. This organization rejected the White Paper, and produced a document entitled “A Declaration of Indian Rights: The BC Indian Position Paper.” Also called the Brown Paper, this document asserted that Indigenous peoples continued to hold Aboriginal title to land. The Brown Paper aimed to protect the special and legal relationship between First Nations and the federal government. It also sought self-determination for Indigenous peoples.

Similar documents and policies were passed by organizations in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and in eastern Canada. Public demonstrations and marches denounced Trudeau’s White Paper, demanding fair and appropriate action on Indigenous issues. This movement is often referred to as “Red Power.” (See also Indigenous Political Organization and Activism in Canada.)

Aftermath and Significance

In response to the backlash, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau withdrew the White Paper in 1970 and angrily stated: “We’ll keep them in the ghetto as long as they want.” Indigenous activists and their allies continued to work on issues arising from this time period. In 1973, the Supreme Court decided on the case Calder v. British Columbia, agreeing that Aboriginal title to land existed before European colonization of North America. The 1982 Constitution Act included section 35, which recognized and affirmed Aboriginal and treaty rights within Canada. (See also Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Many, however, continue to claim that the spirit and intent of the 1969 White Paper and the handing over of responsibilities to Indigenous peoples by Canada continues to be a long-term goal of successive federal governments. This was most evident during the Meech Lake Accord constitutional negotiations, which excluded Indigenous peoples and resulted in Manitoba Member of the Legislative Assembly Elijah Harper’s “no” vote, which helped scuttle the entire agreement. The legacies of the 1969 White Paper continue to be felt today in government policy meetings, and Canadian and Indigenous activist groups, academic circles and grassroots communities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom