Every nation engaging in war emerges changed and diminished in various ways. Some costs are obvious, such as the immediate human and financial toll. Some take longer to play out, such as the emotional and psychological scars on those who survive, and the lingering fallout for a society that has many of its best and brightest torn from its midst suddenly, and forever.

That has been the case for Canada, despite being on the winning side in both of the last century’s world wars. Few historians have described the consequences more ably or comprehensively than Tim Cook. The author of five related books and many essays, he is adjunct research professor at Ottawa’s Carleton University and director of research at the Canadian War Museum.

As he writes: “The Great War forever changed Canada.” A nation of fewer than eight million people in 1914 sent 630,000 of them to war; more than 66,000 died. At the same time, a war fought because of Canada’s unwavering support For Great Britain concluded with the country feeling a greater sense of independence. Every Canadian was touched in one way or another. As we see in these essays on the 100th anniversary of the start of the war, the conflict changed our country and the world forever – in ways that still resonate today.

Anthony Wilson-Smith

Publisher, The Canadian Encyclopedia

That has been the case for Canada, despite being on the winning side in both of the last century’s world wars. Few historians have described the consequences more ably or comprehensively than Tim Cook. The author of five related books and many essays, he is adjunct research professor at Ottawa’s Carleton University and director of research at the Canadian War Museum. As he writes: “The a Great War forever changed Canada.” A nation of fewer than eight million people in 1914 sent 630,000 of them to war; more than 66,000 died. At the same time, a war fought because of Canada’s unwavering support For Great Britain concluded with the country feeling a greater sense of independence. Every Canadian was touched in one way or another. As we see in these essays on the 100th anniversary of the start of the war, the conflict changed our country and the world forever – in ways that still resonate today.

Anthony Wilson-Smith

Publisher, The Canadian Encyclopedia

Canada's Soldiers

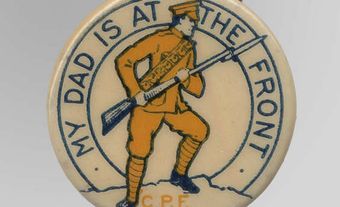

Canada had a professional army of a mere 3,100 men when the country found itself at war in 1914. The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) would consist of citizen soldiers from across the Dominion.

Men enlisted out of a sense of adventure, because of pressure from friends and authority figures, to escape an unrewarding job or an unhappy home life, and because it was widely thought the war would be over by Christmas. Within a few months, however, machine guns, artillery, and rapid-firing rifles left hundreds of thousands killed on the Western Front. Yet even as the war appeared to have no end, Canadians continued to enlist by the tens of thousands until late 1916, indicating that many believed in the justness of the war. Others simply enlisted for any of the other countless reasons to serve in uniform and collect the steady pay of $1.10 a day for privates.

The 425,000 Canadians who went overseas paid a high price for their service, with the total number of dead and wounded numbering 234,741.

(See The Canadian Great War Soldier)

Guns and Gardens

The First World War intruded into all aspects of children's lives. In school, students were taught that the British Empire was fighting for liberty against the evil and militaristic German “Hun.”

Girls were encouraged to band together in sewing groups. Knitted socks for soldiers were material evidence that the boys fighting overseas had not been forgotten by their grateful country or their families.

Local food production by children was encouraged. Patriotic stories circulated of generous youth cultivating Victory Gardens, and banners in schools claimed that the Dominion's youth were battling Germany’s Kaiser by “artichoking” or “beeting” him with their Victory vegetables.

Some 20,000 underage young men actually enlisted for overseas service. Thousands served in the trenches, including a 12-year-old. By war's end, about 2,000 underage Canadian soldiers had been killed.

(See Canadian Children and the Great War)

Art, Film and Photos

The Canadian War Records Office (CWRO) sent photographers, painters, and cinematographers into the field to capture the actions of Canadian soldiers for all history.

Canadian photographers began shooting more than 6,500 images of the stark evidence of the destruction and heroism of the Canadian soldier in the trenches. Combat film cameramen also roamed the front and rear areas.

Canadians A.Y. Jackson, William Beatty, C.W. Simpson, Arthur Lismer, Frank Johnston, and F.H. Varley, were among those enlisted to paint the war. This rare opportunity had a profound influence on the artists’ subsequent careers and in the development of Canadian art.

(See Documenting Canada's Great War)

The Air War

“The aeroplane is an invention of the devil, and will never play any part in such a serious business as the defence of the nation,” thundered Canada’s Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, at the start of the First World War. In fact, the airplane would go through a massive technological evolution during the course of the war and forever change the nature of warfare.

Canadian William Barker became the most successful scout pilot of the Italian Front, winning the Victoria Cross.

Raymond Collishaw commanded a group of four other Canadians who were known as the Black Flight. Fighting the cream of the German air force, they were a deadly team.

Even more famous was Canada’s William ‘Billy’ Bishop, who proved a brave observer over enemy lines. Bishop finished the war with 72 kills, the second highest in the British empire.

(See The Great War in the Air)

Leadership

Most of the senior officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force were drawn from the country's middle class — lawyers, engineers, professional soldiers, businessmen, farmers, and even a dentist. These men would lead Canada’s fighting forces in the most costly war the Dominion would ever experience.

The Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, would initially select most of the senior commanders in the CEF. Hughes’s three most important appointments were the CEF’s three infantry brigadiers: Malcolm Mercer, Richard Turner, and Arthur Currie. Each would command a brigade of four infantry battalions, about 4,000 men in total (and in 1917 Currie would assume overall command of the Canadian Corps, Canada's main fighting force.)

The brigadiers gathered together staff officers who assisted in critical administrative work. These staff officers were vital in ensuring proper training, the efficient movement of men and matériel, and the taking of a commander’s orders and translating them into actionable duties. Many of the staff officers were British-born professional soldiers on loan to the Canadians. As the Canadians matured, they took over command and staff positions.

(See Canadian Command in the Great War)

Shock Troops

The Canadian Corps, a force of 100,000 soldiers by late 1916, fought for the entire war on the Western Front. The Front stagnated as vast armies faced off against each other in underground fortresses and across seemingly empty battlefields. To go above ground invited mass death, as witnessed in the battles of 1914-1916.

But as the war progressed, armies introduced new weapons and tactics in the attempt to break the stalemate. Canadians were at the forefront of this evolution, earning a reputation as shock troops whose innovations helped break the conundrum of the trenches.

These reforms were the basis of victories such as at Vimy Ridge in 1917, and later at Amiens in 1918. That operation was the culmination of four years of tactical reforms, welded together in a combined-arms strategy that saw the infantry advance behind creeping artillery barrages, with tanks and armoured cars thrusting forward, fighter planes shooting up ground targets and reporting back to headquarters on advances or enemy targets, and machine guns and mortar fire, along with chemical agents, further harassing enemy positions.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom