Traditionally, the Inuit were a semi-nomadic people adapted to an unusually harsh landscape and climate, and whatever art they practised tended to be functional — spear heads, knives, clothing, shelters, masks and other objects for use in shamanic rites. What we tend to think of as art — drawings, paintings and sculptures whose primary purpose is aesthetic and social — was by and large not practised by the Inuit until their traditional life began to vanish in the 1950s. Now going on the second and third generation of modern Inuit artists, Inuit art has increasingly become a force on the international art scene.

Dorset Culture

Dorset culture, which began to evolve between 700 BCE and 500 BCE, can be called the first Indigenous Canadian Arctic culture. Dorset art is thought to have served a magical or religious function. It is characterized by its perfectionist craftsmanship and refined beauty, which is especially exemplified in the Tyara maskette.

Pitseolak Ashoona

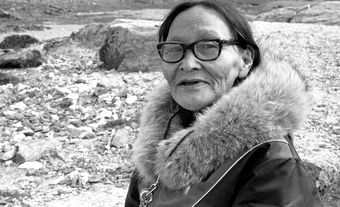

The Inuit artist Pitseolak Ashoona was born in a skin tent between 1904 and 1908 while her family was making a spring trek from Salluit, in the Nunavik region of Arctic Québec, to the south coast of Baffin Island (Qikiqtaaluk), during an era when Europeans still had relatively little impact on the Far North and when the Inuit still lived on the land as semi-nomadic subsistence hunters and trappers. After her father died in the early 1920s, she married Ashoona, an accomplished hunter, and continued to live a traditional life, tending to the needs of her husband and children and making the parkas, footwear and shelters that are indispensable to survival in the Arctic. It was not until long after the death of her husband that, living in the relatively new settled community of Cape Dorset (Kinngait), Pitseolak got involved with the arts and crafts program spearheaded by James and Alma Houston . Pitseolak Ashoona was one of the first generation of accomplished, full-time Inuit artists, and her work harkens back to the life and legends she grew up with.

Kenojuak Ashevak

Like Pitseolak Ashoona, Kenojuak Ashevak grew up on the land in the traditional, semi-nomadic lifestyle. Her father was a respected shaman who believed he could predict the weather and transform himself into animals. After three years in Parc Savard Hospital in Québec City for tuberculosis, she returned to Cape Dorset and got involved in James Houston’s printmaking workshops and the West Baffin Cooperative. Kenojuak’s works became well known quickly because of her bold sense of line and compelling designs. Her iconic The Enchanted Owl has feathers wheeling from dark to blazing orange around a purple spotted owl; in Wolves in Spring , the wolves creep in the foreground, behind them spotted purple hills with a river rising vertically up through them. In both of these works, one has the sense that the animals are part of a dream or a vision.

Annie Pootoogook

While both Pitseolak’s and Kenojuak’s work provides a window into the traditional life on the land and the ancient mythologies, the work of Annie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona is rooted in the reality of contemporary Inuit life.

Annie Pootoogook’s drawings depict ordinary, day-to-day life in the Arctic, including its darker aspects — alienation, depression and addiction — which she knew well. The Homecoming (2006), for instance, features a large, multigenerational family, including old women and swaddled infants, dressed for winter and waiting in what looks like an empty bus station, with trucks visible in the snowy landscape outside the window. Memory of My Life Breaking Bottles(2001–02), on the other hand, has a stark figure smashing bottles against the wall of a house. The rage in Memory of My Life Breaking Bottles is rooted in frustration with her struggle with alcoholism and in a despairing sense of helplessness and purposelessness.

Shuvinai Ashoona

Shuvinai Ashoona’s work, by contrast, shifts between intricate, nearly abstract Arctic landscapes, surreal versions of contemporary life, and phantasmagorical mythologies — often all at the same time. In Untitled (Angel Bringing Tools) (2006–07), a yellow, winged figure holding a set of traditional Inuit tools stands in the foreground, and on a rock in the background is an eagle with outstretched wings and a white owl. The soft, ghostly Untitled (End of Worlds) (2011) portrays a small coffin with a body visible inside. The coffin is rolling on wheels, which are globes of different worlds, along the ocean floor, fish swimming above it. In an indication of the degree to which the younger generations of Inuit artists are now part of the broader Canadian and international art worlds, Ashoona has also undertaken joint exhibits and collaborative works with Toronto-based artist Shary Boyle. The elaborate and amusingly titled InaGodadavida (2015) — the title alludes to the 1968 cult acid rock song by Iron Butterfly — combines both Ashoona’s and Boyle’s taste for the fantastic and psychedelic: there is a floating octopus, a dark river, a red planet, a starry sky, and a huge woman with the dark crown of a baby’s head emerging from between her legs. Ashoona’s work is neither nostalgic nor despairing; it suggests that the powerful, shamanic worldview of the Inuit has a place in 21st century life.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom