Sir William Ralph Meredith, lawyer, judge, politician, educator, public servant (born 31 March 1840 in Westminster Township, Upper Canada; died 21 August 1923 in Montreal, QC). William Ralph Meredith had a long tenure as the opposition leader in the Ontario legislature, leading the provincial Conservatives to five consecutive defeats between 1879 and 1894 (see Conservative Party). His findings while conducting the Meredith Commission on workmen’s compensation between 1910 and 1913 resulted in reforms to labour legislation that formed the basis of Canada’s modern workers’ compensation system, which follows the “Meredith Principles.”

Early Life and Career

William Ralph Meredith was the oldest of 14 children. His father, John, emigrated to Westminster Township (present-day London, Ontario) in 1834 and worked in various civil service positions, rising to clerk of the division court of Middlesex County in 1847. William’s seven brothers included Ontario’s chief justice of common pleas and University of Western Ontario chancellor Richard Martin Meredith, and Bank of Montreal president Henry Vincent Meredith. (See also Western University.)

Meredith’s legal career began when he articled to London lawyer Thomas Scratcherd in 1856. After studying at the University of Toronto, he was called to the bar in 1861, then entered a 15 year partnership with Scratcherd, whom he succeeded as London’s city solicitor in 1876. He later served as the first president of the Middlesex Law Association before moving his practice to Toronto in 1888, when he became an honorary faculty member at the University of Toronto.

Political Career

First elected as a Conservative in a provincial by-election in London in 1872, William Ralph Meredith became deputy party leader in 1878, then succeeded Matthew Crooks Cameron as party leader in January 1879 (see Conservative Party). Meredith led the Conservatives to defeat in five consecutive provincial elections (1879, 1883, 1886, 1890, and 1894), losing each time to Liberal Premier Sir Oliver Mowat (see Liberal Party; Premier).

As Conservative leader, Meredith campaigned to reducing public spending, supported giving municipalities control over liquor licensing, and wanted to place the education portfolio under the watch of a non-partisan chief superintendent instead of a cabinet minister. While Meredith supported near-universal male suffrage, including voting rights for non-reservation Indigenous men, he opposed female suffrage in any form. (See also Right to Vote in Canada; Indigenous Suffrage; Women’s Suffrage in Canada.) He had traditional views about the role of women of society, to the point of opposing the admission of women to the University of Toronto’s University College and serving on the Law Society committee which, in 1892, rejected Clara Brett Martin’s application to become a lawyer.

Meredith tended to view his political activities as a part-time role, ignoring usual duties such as calling caucus meetings or taking care of constituency matters. He maintained poor relations with federal Conservatives, especially over Roman Catholic separate schools, which Meredith felt enjoyed unfair advantages. (See also Catholicism in Canada; Separate Schools.) The issue also destroyed Meredith’s opportunity to join the federal cabinet following the death of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1891. Meredith’s admission was vetoed by federal justice minister Sir John Thompson, who was influenced by Catholic bishops.

Judicial Career

Following the Conservative defeat in 1894, William Ralph Meredith was appointed chief justice of the common pleas division of the Ontario High Court of Justice. He was knighted in 1896. He was named chief justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal in 1913. As a jurist, he was praised for his knowledge of municipal law and tended to follow strict precedents. He is reported to have often reprimanded unprepared barristers.

In an appreciation published in the Canadian Bar Review in 1923, William Nassau Ferguson observed that Meredith “was an able, ready, open fighter who sought an argument in the open and desired that counsel and his brothers should not accept his ‘say so’ without consideration or discussion, but should combat his contentions, statements and propositions and battle with him through a logical, reasoned argument to the desired result.”

Workers’ Compensation

In 1885, William Ralph Meredith introduced a workers’ compensation bill which was inspired by British legislation. While some of his suggestions were incorporated into the Workmen’s Compensation for Injuries Act of 1886 (the first such legislation in Canada), Meredith believed it was too accommodating to employers. For example, workers could not sue if their job was considered hazardous.

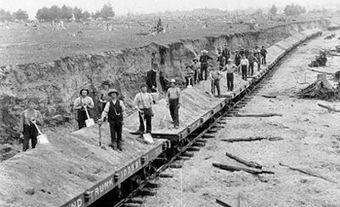

During the early 20th century, industrial accidents rose as the number of manufacturers increased. In June 1910, Meredith was appointed to lead a one-man commission to develop a replacement for the Workmen’s Compensation for Injuries Act. He conducted hearings with labour leaders, the Canadian Manufacturers Association and insurance companies, and examined laws in North America and Europe, travelling to the later in the fall of 1912.

The recommendations of Meredith’s final report, issued in 1913, provided the basis for the Workmen’s Compensation Act, which the October 1913 edition of the Journal of Political Economy believed was “striking testimony” to his “challenging boldness and progressiveness.” Its features, which became known as the “Meredith Principles,” included no fault compensation, collective liability funded by employers, and the creation of a Workmen’s Compensation Board that oversaw claims. Meredith anticipated that if they carried the cost, employers would be motivated to create safer workplaces. While labour organizations supported the bill, the Canadian Manufacturers Association declared the bill a “direct menace to the manufacturers of the province.” The legislation passed in April 1914.

Other Activities

William Ralph Meredith was appointed to the University of Toronto senate in 1895, then served as its chancellor from 1900 until his death.

Meredith served as a political mentor to Sir James Pliny Whitney, advising him not to leave politics in the early 1890s because he had “such good prospects.” When Whitney became premier in 1905, Meredith acted as a personal adviser, often scrutinizing bills before they reached the legislature—in 1906 alone, Meredith assisted with bills that created the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario (the forerunner of Ontario Hydro) and the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board (later the Ontario Municipal Board) and reformed the governance of the University of Toronto. He led or served on committees at all political levels, including the Civic Improvement Committee in Toronto, a review of federal wartime contracts, and an investigation concerned with the administration of the Ontario Temperance Act. (See also Temperance Movement in Canada; Prohibition in Canada.)

Legacy

Historian Charles W. Humphries felt that William Ralph Meredith, “a man not always admired by his supporters, led a party weakened by shortcomings in men, money, and organization, handicapped by Tory dominance nationally, sapped by religious controversy, and frustrated by continual failure.” Modern Canadian workers’ compensation programs still consider the “Meredith Principles” as their basis.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom