Robotics is the branch of engineering that concerns robots: reprogrammable, multifunction manipulators designed to move objects and complete tasks through a variety of programmed motions. The field includes the conception, design, manufacture and operation of such machines. Robotics overlaps with a variety of other electronic and engineering disciplines including artificial intelligence (AI), bioengineering, computer science, mechatronics (the engineering of both electrical and mechanical systems) and nanotechnology. In the late 20th century, Canada distinguished itself in the field with the development of the Canadarm for space missions. Despite the challenges of competing in the international market, Canadian companies, institutes and researchers are now world leaders in the development of AI applications for robotics.

Background

Since ancient times, human beings have conceived of machines that could perform tasks normally reserved for the living. With the development of precision metalworking in the Middle Ages, craftsmen in various cultures began to design self-operating machines (also known as automata) that could perform limited imitations of some human behaviours. (See Artificial Intelligence: Historical Background.)

The word robot was first used by the Czechoslovak writer Karel Capek in 1921 in a play entitled R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). The play is a satire on mechanized society in which the automatons created by Rossum and his son to serve humankind go out of control with disastrous consequences.

In 1940, the term appeared in the short story “Robbie” by science fiction author Isaac Asimov. With his 1950 novel I Robot — mainly a compilation weaving together earlier stories (including “Robbie”) — Asimov influenced many of the directions and concepts of modern robotics.

The same year “Robbie” was published, the patent for the first industrial robot was granted to engineer Willard L. G. Pollard for a spray-painting machine. American engineer Joseph Engelberger (1925–2015) is widely regarded as the father of robotics in North America. His company, Unimation, introduced the robotic arm to automobile manufacturing in 1961.

History of Robotics in Canada

Well before robots were used in Canadian industry, colonists brought examples of automata created by European craftsmen. One such device, a mechanical doll created by Léopold Lambert around 1890, is preserved in the McCord Museum’s collection in Montreal.

One of the first industrial robots to be placed in full operation anywhere in North America is reported to have been in a candy factory in Kitchener, Ontario, in the early 1960s.

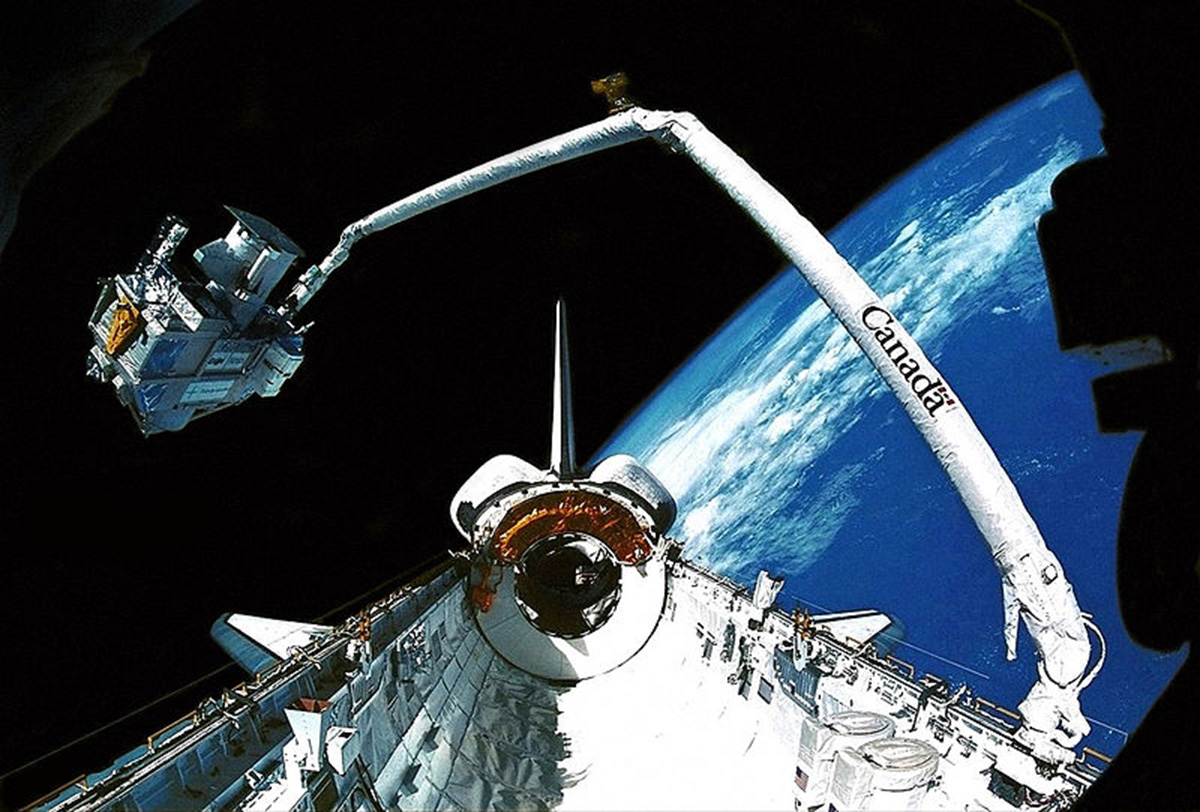

Canada’s best-known contribution to robotics is the Canadarm. A manipulator able to withstand the harsh radiation in space, it was first used by the crew of the NASA space shuttle Columbia in 1981. On subsequent missions, astronauts used it to remotely construct what would eventually become known as the International Space Station (ISS).

The Canadarm derived from technology developed by Toronto-based engineering firm Dilworth, Secord, Meagher and Associates (DSMA Atcon) in the 1970s. DSMA Atcon had developed a robot with shielded electronics able to load fuel into Canadian-built CANDU reactors without subjecting engineers to the high radiation levels found within operational reactors. (See also Nuclear Power Plants.)

For almost 40 years, the original Canadarms deployed on board the various US space shuttles (along with the Canadarm2 currently on board the ISS) have performed the important functions needed to keep the ISS operational.

Did you know?

The Canadarm2 has attached and disassembled various ISS modules. It can also dock and undock manned and unmanned cargo modules, capture and release space shuttles, and guide the positioning of astronauts during space walks.

The company behind Canadarm2, formerly MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA) and now Maxar Technologies, hopes to create a new, improved Canadarm incorporating advanced artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. The arm would form part of NASA’s Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (LOP-G) project — a moon-orbiting space station — but has been contingent on support from the federal government. In early March 2019, the government promised $1.9 billion in funding for this “third generation” Canadarm over 24 years. Its commitment could open the door to funding for new robotics technologies.

An artist’s concept of Canada’s smart robotic system located on the exterior of the Gateway, a small space station in orbit around the Moon.

Contemporary Uses of Robots in Canada

Contrary to the popular science fiction images of robots, real robots are typically industrial manipulators: computer-controlled arms and hands. They are common in the automotive and manufacturing industries, where their uses normally include arc welding, spot welding and spray painting. They also transport materials in factories and hospitals in addition to performing tasks too unsafe or repetitive to interest humans. As they replace workers in an increasing number of functions, robots have been blamed for growing unemployment.

The dangerous environments in which robots explore and operate include deep space, deep sea and underground mines. Mining robots are automated vehicles typically used for accessing dangerous places, exploring, digging and loading and transporting materials.

Robots are also used beyond manufacturing, logistics and exploration. For example, several museums around the world have experimented with robotic tour guides. In the summer of 2014, two Canadian professors and their research teams sent a hitchhiking robot (called HitchBOT) on a journey across the country. The following year, HitchBOT was acquired by the Canada Science and Technology Museum. Robots can be used to prepare and serve food, although such applications are still rare in the Canadian restaurant industry.

Robots are expected to proliferate in the coming decade, driven in large part by home robotics (e.g., vacuum cleaners), autonomous cars and the growth of interconnected “Internet of Things” applications (see also Computers and Canadian Society).

Current Robotics Research in Canada

Although carried out by a relatively small number of researchers, current Canadian robotics research in universities, industry and government laboratories is highly regarded. Montreal is generally considered a world-class centre of excellence in robotics and AI. Toronto is almost as well regarded. Both cities owe their prominence to the highly educated local workforce and large local concentrations of academics who encourage funding partnerships between Canadian universities and international tech firms.

The willingness of various government agencies to fund such partnerships has been a key component of Canadian success in the field. The public-private science and innovation model expands fundraising capabilities beyond traditional academic communities by allowing the private sector to partner with government. Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s Liberals first outlined the federal government’s commitment to supporting public-private partnerships in their 1994 science and technology review. Shortly afterwards, it became federal policy. Because public-private partnerships have traditionally focused on large infrastructure programs and investment in physical assets, the Canadian focus on research and development is relatively unique.

Challenges of Commercial Robotics in Canada

Canada’s leadership in the research and development aspects of robotic technologies does not necessarily lead to commercial domination. Of the top 21 industrial robotics companies in the world in 2018, not one was based in Canada, although several had Canadian branch offices. The lack of intellectual property and legal protections for Canadian inventions makes it easier for well-funded international organizations to co-opt Canadian inventions and export them for their own purposes.

For example, in 2017, the chairman of Google holding company Alphabet publicly thanked Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for Canada’s publicly funded AI innovations, which the company now uses “throughout [its] entire business” as a “major driver of [its] corporate success.”

The Canadarm program also serves as a case study of this issue. While it did lead to a variety of useful medical and industrial applications, the Canadian companies involved did not go on to dominate the international marketplace in any meaningful way. MDA, the Canadarm’s prime contractor, even ended up reincorporating and relocating to become US-based Maxar Technologies. This allowed it to bid on US government contracts related to robotics, which require the technology to originate from US owned and operated corporations.

AI and Modern Robotics in Canada

Today, the development of new AI applications is the largest source of growth in the Canadian robotics industry. Artificial intelligence-based software applications increasingly act as controlling mechanisms for manufacturing and robotics equipment. They allow the machinery to learn new processes that increase the equipment’s flexibility and usefulness.

Canada has funded and supported AI pioneers such as Yoshua Bengio (of the University of Montreal and the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms, or MILA), Yann LeCun (of Facebook) and Geoffrey Hinton (of the University of Toronto’s Vector Institute and Google).

From left to right: Rich Sutton, Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio at a 2016 panel discussion in Toronto, Ontario. (Courtesy Steve Jurvetson/flickr CC)

These and other internationally renowned researchers have in turn attracted many foreign students —and foreign investment — to AI research labs in Canada. For example, Element AI, with offices in Montreal, Toronto, London (UK) and other locations raised US$102 million in 2017, led by San Francisco-based venture capital firm Data Collective. It will use the funding to roll out a series of software-based AI applications in robotics, finance, transportation, manufacturing, cybersecurity and logistics. The firm has also received funding through China-based conglomerate Tencent Holdings and through Intel, based in California’s Silicon Valley.

One example of public-private partnership in AI research is the IBM Innovation Space in Toronto. The $54 million initiative funded by IBM, the Ontario Centres of Excellence and the Ontario government aims to drive innovation in healthcare, natural resources and financial services. The space currently provides networking, funding, mentorship, industry expertise and support services to 13 innovative local AI and robotics start-ups.

Sun Life, Adobe, LG and TD Bank are also involved in this area, as is the Canadian Institute for Applied Research (CIFAR). The research institute has more than 400 fellows, scholars and advisors from 22 countries. In 2017, the Canadian government picked CIFAR — in partnership with MILA, the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute (Amii) and the Vector Institute — to lead the $125 million Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy. Given the increasing integration of AI and robotics, the strategy’s plan to boost AI in Canada stands to benefit the country’s robotics industry.

Alberta minister of advanced education Marlin Schmidt (left) and then premier Rachel Notley (right) demonstrate the Bento robotic arm from the University of Alberta’s Artificial Machine Intelligence Institute. Photography by Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, 2018. (Courtesy Premier of Alberta/flickr CC)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom