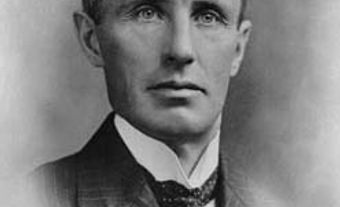

Oscar Douglas Skelton, author, professor, civil servant and head of the Department of External Affairs from 1925 to 1941 (born 13 July 1878 in Orangeville, Ontario; died 28 January 1941 in Ottawa, Ontario). Skelton advised prime ministers William Lyon Mackenzie King, Arthur Meighen and R.B. Bennett to develop an independent foreign policy that favoured Canadian interests over Canada’s long-standing relationship with the United Kingdom. Skelton also developed the modern Department of External Affairs (now Global Affairs Canada) in the aftermath of the 1931 Statute of Westminster and set key precedents that shape Canadian foreign policy to the present day.

Family

Oscar Douglas Skelton was the second child and only son of Jeremiah Skelton and Elizabeth Jane Hall, primary-school teachers in Caledon, Ontario, from Northern Irish Protestant families. The family moved often in Ontario, and Jeremiah was involved in numerous civic organizations, serving as a town councillor and secretary of the board of trade in Shelburne and president of the Stormont Teachers’ Association in Cornwall, Ontario.

Education

After completing high school in Orangeville, Oscar Douglas Skelton received scholarships to both the University of Toronto and Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. Skelton earned a master of arts degree in classics and English literature at Queen’s University in 1899 and then returned to the university for an additional year of study in Greek in 1900. He then moved to the United States to pursue a PhD in economics and politics from The University of Chicago, which he completed in 1908, writing his dissertation on “The Case Against Socialism.” During his doctoral studies, he was the assistant editor of The Booklovers Magazine in Philadelphia, where his sister Emma worked as a stenographer.

Marriage and Children

On 16 August 1904, Oscar Douglas Skelton married Isabel Murphy at her family’s farm in Antrim, Ontario. They spent five months travelling in the United Kingdom and Europe for their honeymoon, and Skelton later told the Standard newspaper in Cornwall that he had seen “no country during his tour that he likes better than Canada, and none so intelligent, industrious and prosperous as Canadians are.” Skelton described his wife as “my rock,” but they were often apart from each other for long periods of time because of his academic research and government work.

The Skeltons had three children: Douglas Alexander (1907–50), a political science professor and an assistant deputy minister of trade and commerce in Canada; Herbert Hall (1909–87); and Sheila Isabel Halliday (1918–98), who married Arthur Redpath Menzies, Canada’s high commissioner to Australia and recipient of the Order of Canada for his efforts to improve the relationship between Canada and China.

Academic Career

In 1909, Oscar Douglas Skelton became the John A. Macdonald Professor of Political Science and Economics at Queen’s University — a position he held until 1925. Skelton was also the dean of arts at Queen’s University from 1919 to 1925. He was a popular professor, nicknamed “Skelly” by his students.

Skelton was a prolific author and public intellectual. His first book, Socialism: A Critical History, which was published in 1911, was praised by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin as the strongest critique of socialism written from a “bourgeois” perspective. Skelton developed a strong rapport with former prime minister Wilfrid Laurier and was invited to become his official biographer in 1914. The two-volume Life and Letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier was published in 1921. Skelton’s other books included The Life and Times of Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt (1920) and The Railway Builders: A Chronicle of Overland Highways (1916).

Skelton expressed his views on economics, history and Canadian politics in a regular column in the Queen’s Quarterly journal. While he supported Canada’s involvement in the First World War in support of “honour and freedom and democracy,” he opposed conscription. This stance resulted in prominent Queen’s University alumni, including Winnipeg businessman and aviation pioneer James Armstrong Richardson, demanding his resignation. Skelton had the support of Queen’s University principal R. Bruce Taylor, and the controversy surrounding his views on conscription became part of a wider discussion about academic freedom.

Department of External Affairs

Oscar Douglas Skelton impressed Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King when he delivered a lecture entitled “Canada and Foreign Policy” to the Ottawa members of the Canadian Club in 1922. Skelton argued that Canada should oppose a unified foreign-policy agenda for the entire British Empire and Dominions developed in the United Kingdom and should instead be self-governing in foreign affairs, stating “the stand that Canada is to take must be decided in Canada by Canada’s elected representatives — by men responsible to the people of Canada.” Mackenzie King hired Skelton as a part-time foreign-policy consultant and invited him to be the Canadian government’s expert adviser at the 1923 Imperial Conference in London. In 1924, Skelton took a leave of absence from his university responsibilities to attend meetings of the League of Nations in Geneva as a consultant for the Canadian government.

In March 1925, Mackenzie King appointed Skelton undersecretary of state for external affairs. Skelton’s academic career at Queen’s University came to an end, which he described to Taylor as “the most difficult decision I have ever had to make.” He moved with his family to the Rockcliffe neighbourhood of Ottawa.

Skelton played an important role in the 1926 Imperial Conference, which led to the Balfour Report — that the United Kingdom, Canada and the other Dominions were “equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs.” Skelton described the Balfour Report as “an epoch-making document.” In 1929, he travelled to London to attend the Conference on the Operation of Dominion Legislation, which recommended legislative autonomy for the Dominions. He was, therefore, a key figure in negotiations with the British government that led to the 1931 Statute of Westminster, which granted Canada and the other self-governing Dominions autonomy over their respective foreign-policy decisions.

Skelton had a strong working relationship with Mackenzie King, who shared his views on the importance of Canadian autonomy in foreign affairs and encouraged him to remain prime minister during the King-Byng Affair. Mackenzie King and Skelton also became close friends, enjoying holidays together, including three weeks in the Caribbean in 1938. Nevertheless, Skelton remained in his role in external affairs during the brief period when Arthur Meighen was prime minister in 1926 and during R.B. Bennett’s time as prime minister from 1930 to 1935, declining the opportunity to return to Queen’s University as principal in 1930. Bennett later recalled that he intended to replace Skelton, but “then I began to find that I couldn’t get along without him. He knew everything.” Skelton introduced comprehensive examinations for prospective departmental officers in 1927 and expanded the department, hiring people who would go on to have long and distinguished careers, including Hugh Llewellyn Keenleyside, co-founder of Carleton University, and future prime minister Lester B. Pearson.

Skelton favoured closer links between Canada and the United States, including reducing tariffs on trade and negotiating a new trade deal with the United States in 1935, but recognized that these initiatives would be opposed by the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association during the Great Depression. That same year, he was rumoured in the press to be Mackenzie King’s choice for Canadian minister (ambassador) to Washington, but he remained at the Department of External Affairs. At the 1932 Imperial Economic Conference, hosted by Governor General Lord Bessborough in Ottawa, Skelton opposed closer economic integration of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realms, objecting to a centralized imperial economic secretariat.

The Coronation of King George VI

Oscar Douglas Skelton, his wife, Isabel, and their daughter Sheila attended the coronation of King George VI in 1937 as part of the Canadian delegation with Mackenzie King and Pearson. Skelton refused to wear court dress for the occasion, prompting Canada’s high commissioner to the United Kingdom and future governor general Vincent Massey to remark, “Some of our Canadian party held views that savoured of Jacksonian democracy rather than the tradition we are supposed to have inherited.”

The Second World War

Oscar Douglas Skelton viewed the Nazi Party in Germany as “reckless gangsters” engaged in “disgusting and deplorable” violence against Jewish people. He telegraphed Bennett from the League of Nations in 1933 that “Nazi forces are drunk with success and seek victims for suppressed emotions.” But he objected to Canada entering the Second World War just one week after the British declaration of war in 1939 — a decision made with minimal debate. Skelton’s concerns about Canada becoming immediately involved in a European war strained his friendship with Mackenzie King. Once war had been declared, however, Skelton worked toward the success of Canada’s war effort, serving on the Cabinet War Committee. As Mackenzie King observed in 1940, “[Skelton] now sees that the real place to defend our land is from across the seas.”

Death

Oscar Douglas Skelton suffered his first heart attack in 1937 and died from a subsequent heart attack while driving in downtown Ottawa in 1941. His car collided with a streetcar near the Parliament Buildings. His death came as a shock to his colleagues. Pearson wrote that, at the Department of External Affairs, “Seldom, I suppose, in any organization has the loss of one man meant so much.”

Legacy

In 1953, friends of Oscar Douglas Skelton and deputy minister of finance W.C. Clark established a memorial foundation at Queen’s University to promote public-policy research. The Department of Political Studies continues to fund Skelton-Clark Fellows. Past Skelton-Clark Fellows include former NDP leader Ed Broadbent and former provincial deputy minister George Thomson.

The O. D. Skelton Memorial Lecture series, which began in December 1991, provides a scholarly examination of Canadian international relations by prominent Canadian lecturers. Past speakers include Margaret MacMillan, Chrystia Freeland, Michael Ignatieff and Skelton’s biographer, Norman Hillmer. There is a plaque honouring Skelton in the Skelton Lobby of the Lester B. Pearson Building at 125 Sussex Drive in Ottawa, the headquarters of Global Affairs Canada.

Skelton’s influence on Canadian history and politics has received extensive analysis from historians and political scientists. In his nuanced biography of Skelton, Hillmer challenged the perception of Skelton as reflexively anti-British and isolationist, writing that “[Skelton] saw the Canadian-American relationship, the League of Nations and the British Commonwealth that was growing out of the British Empire as beginnings in the establishment of a new international order marked by peaceful collaboration, with Canada taking a modest but committed place in the society of nations.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom