The history of France as a colonial power in North America began during the 16th century, during the era of European exploration and fishing expeditions. At its peak, the French colony of New France stretched over a vast area from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Louisiana. The French presence was characterized by extensive trade, as well as by recurrent conflicts with the Indigenous peoples, who were established over a wide area that France sought to appropriate. Some objectives motivating the French colonization were related to evangelization and settlement. Following the British Conquest, New France was ceded to Great Britain in 1763 and became a British colony. (See Treaty of Paris 1763.)

(This article is the full version of the text regarding New France. For a plain-language summary, please see New France (Plain Language Summary).)

Indigenous peoples had occupied the lands that became New France for millennia and the Vikings had been frequent visitors since the end of the 10th century (see Norse Voyages). However, it was primarily from the founding of Quebec City in 1608 to the ceding of Canada to Britain in 1763 that France left its mark on the history of a continent where it succeeded in controlling three quarters of the land, including Acadia. In Canada, notably in the St. Lawrence Valley (see St. Lawrence Lowland), France settled a population which has continued to affirm its vitality and culture to the present day.

Founding and Background

The founding of New France was part of the vast wave of European exploration initiatives in the 16th century. Following in the footsteps of other European powers (England, Spain and Portugal) and the voyages to America by Christopher Columbus in 1492, John Cabot in 1497, and the Corte-Real brothers (see also Portuguese), France became interested in maritime exploration.

In 1524, Giovanni Verrazzano sailed up the eastern coast of America, from Florida to Newfoundland. Later, Jacques Cartier made three voyages of discovery. He took possession of the land in the name of the king of France by planting a cross in Gaspé (see Gaspé Peninsula) in 1534. The following year, he travelled up the St. Lawrence, wintered in Stadacona (site of what is now Quebec City) and continued on to Hochelaga (present-day Montreal). During the winter, twenty-five of his men died of scurvy. In 1536, he went back to France.

In 1540-1541, Jacques Cartier returned to America and attempted to establish a colony at the mouth of Cap Rouge River. While the stated purpose behind the organization of these voyages was religious, the economic reasons took even greater precedence. The hope of finding a passage to India was constantly affirmed (see Northwest Passage). In 1534, the king asked Jacques Cartier to “discover certain islands and countries where there are said to be great quantities of gold and other riches.” During his final voyage, the explorer reported finding minerals he believed to be gold and diamonds. In actual fact, they were only iron ore and quartz (see Diamonds of Canada). At this point, France lost interest in that distant land until the end of the 16th century.

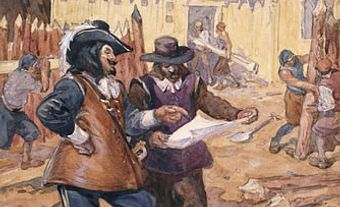

In the interim, however, and even before the arrival of the great explorers, the French showed interest in the region’s fishing resources (see Fisheries). The presence since the early 16th century of Basque, Breton and Norman fisherman on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland has been confirmed. As early as 1550, fishermen were drying fish on the region’s shores, making contact with the Indigenous peoples and bringing furs back to France. From 1580 to 1590, a number of fishermen turned toward the fur trade (see Fur Trade). This activity eventually drew the French further into the interior of the continent. Thus, private enterprise was what lay behind the exploration of America.

Samuel de Champlain, considered the founder of New France, established a settlement in what is now Quebec City in 1608. Like Jacques Cartier, his objective was to find a passage to India. This settlement met the economic imperatives: to get closer to the areas rich in furs, to strengthen contacts with the Indigenous suppliers, and to promote the acquisition of trade privileges. The scope of such an undertaking required the creation of trading companies.

Commercial Administration of the Colony and the Religious Missions

From 1608 to 1663, the administration of the colony was entrusted to the trading companies composed of merchants from various cities in France. Later companies undertook to populate and develop America in return for the privilege of exploiting its resources. The Company of One Hundred Associates — the brainchild of Louis XIII’s great minister, Cardinal Richelieu — administered New France directly or through subsidiary companies from 1627 to 1663. The Company did not, however, achieve the expected results. In 1663, the population barely numbered over 3,000, including 1,250 children who were born in the country. (See Population Settlement of New France.) Less than 1 per cent of the land granted was being farmed. In 1618, Samuel de Champlain anticipated annual revenues of 5 million livres from fishing, mining, forestry, hemp, cloth, and furs. However, only the latter proved profitable (although less than expected). Attempts to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity were no more successful.

During New France’s first half-century of existence, missionary activity reached epic proportions. (See Catholicism.) In 1632, the Jesuits established the Ste Marie Among the Hurons mission. (See Huron-Wendat.) Ville-Marie, which later became Montreal, was the work of mystics and devotees. However, the missionaries ultimately only succeeded in converting a small number of Indigenous People.

A number of political and military events hindered the colonization efforts. The alliances formed by Samuel de Champlain led to wars and created enemies. Quebec City surrendered to the Kirke brothers in 1629. Following the colony’s return to France in 1632, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) were hostile. From 1648 to 1650, they decimated the Huron-Wendat, who were allied with the French.

The fantastical, exaggerated stories of the adventures and misadventures of Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Dollard des Ormeaux attest to the fact that the colony’s very survival was threatened.

In 1663, Quebec City was still only a trading post, a place where the fur trade competed with farming (see History of Agriculture). The meeting of the cultures proved harmful to the Indigenous peoples, who were decimated by war and disease. The French population was very small. The administration of the colony by merchants proved to be a failure. The Company put the destiny of New France into the hands of the king. (See also Compagnie des Indes occidentales.)

Development Under Royal Administration

The development of the colony was stimulated by the intervention of Louis XIV, who made it a true province of France. He provided it with a hierarchical administrative organization, ensured its settlement, extended its territorial boundaries, and allowed the number of economic undertakings to increase. However, before this could be achieved, peace had to be ensured.

Under the orders of the Marquis de Tracy, the Carignan-Salières Regiment erected forts, destroyed villages, and demonstrated the might of the French military. The Haudenosaunee made peace. Four hundred soldiers remained in the country to colonize it. The king also facilitated the migration of some 850 girls of marriageable age ( see Filles du roi). These girls were, for the most part, military orphans. A quick marriage and a high birth rate were encouraged. Twenty years later, when their descendants were old enough to form their own families, the demographic structure had changed. From one woman for every six men (which was the case in 1663), the number of men and women became more or less the same. Thereafter, the population renewal rate was 90 per cent, thanks to the children born in the colony. (See Population Settlement of New France.)

Louis XIV introduced an administrative structure similar to that established in the kingdom’s other provinces and colonies. New France was placed under the authority of the Comptroller General of Finance and, later, under the authority of the Ministère de la Marine. The administration of the colony was entrusted to a governor, who was responsible for military issues and external affairs. An intendant was responsible for justice, the police, and finances ─ basically, all of the civil aspects of colonial administration. A Sovereign Council — which became the Superior Council in 1717 — acted as a court of appeals and registered the edicts of the king.

Resumption of Exploration and Economic Expansion

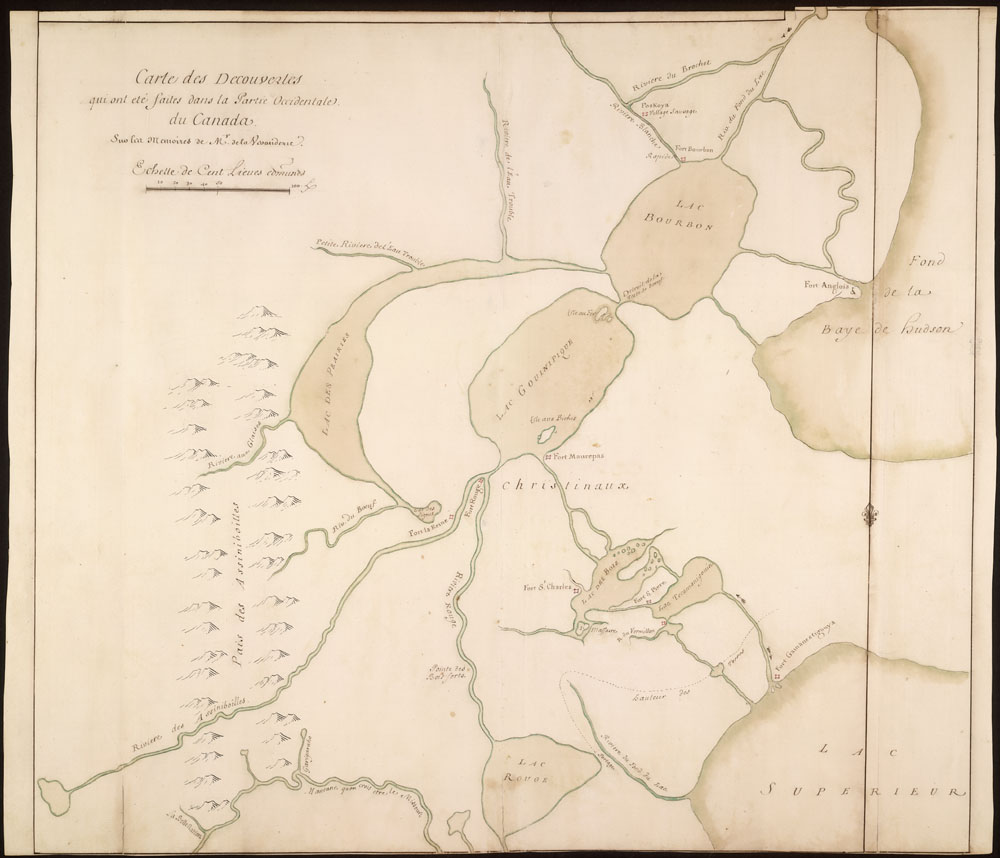

The imperialist ambitions of Louis XIV, the defeat of the Haudenosaunee, and the necessity to rebuild the fur trade network were instrumental in the resumption of exploration of both the Great Lakes and the Mississippi. François Dollier de Casson, Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette, Cavelier de La Salle are examples of famous explorers of this period. However, the wars with the Haudenosaunee resumed in 1682 and the colony had new heroes, such as Le Moyne d’Iberville, to celebrate. The costs of military, political and missionary actions were in addition to the economic imperatives that forced the colony to obtain furs from the Indigenous nations.

Finally, Intendant Jean Talon, solidly backed by Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, launched a dynamic program of development. To agriculture and the fur trade, Jean Talon added naval construction, trade with the West Indies, the cultivation of flax and hemp, fisheries, a brewery, etc. As the economic situation had changed, almost nothing remained of these early initiatives when he left in 1672.

It is difficult to understand the major components of this society in the making. In Acadia, we know of the quality of farming, the importance of fishing and the alternation of the British and French governments. In the Laurentian Valley, while the majority of the population were farmers, they were still primarily clearers of the land. Artisans were not supported by large companies. The fur traders were subjected to increasingly harsh economic constraints, but supplied the only export. Through their involvement in business and as part of the governor’s entourage, the military officers enjoyed a great deal of prestige.

The seigneur had little in the way of income and held his position through his title and the exercise of duties other than those related to the land (see Seigneurial System). Social mobility, which was still possible, allowed the categories and groups to mix.

End of Expansion and Economic Crisis

New France reached the pinnacle of its territorial expansion in the early 18th century. Approximately 250 people were living in ten settlements in Newfoundland. The population of Acadia was almost 1,500. Several hundred people had settled at the mouth of the Mississippi River, while just as many had settled in the Great Lakes region. Hundreds of people fished seasonally on the Labrador coasts. The Saguenay River basin, part of the Domaine du Roi, was the site of several trading posts. At that time, Canada had a population of approximately 20,000. Most of Canada’s population were farmers, spread along a long ribbon of settlements between Quebec City and Montreal.

In the west, a series of trading posts and forts stretched along the communication routes. Finally, somewhat later, La Vérendrye extended the map of the continent to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. But New France was a colossus with feet of clay. The British American colonies were twice as populous and felt surrounded and threatened. Through the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, which marked the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, France ceded Newfoundland, the Acadian Peninsula, and Hudson Bay to Britain. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy passed under the protection of the British. In addition, the 18th century began with a major crisis in the colonial economy. The major export was affected by poor sales in Europe, declining quality, and increased costs. The many young people who came as settlers had no choice other than to work the land.

Recovery in Times of Peace

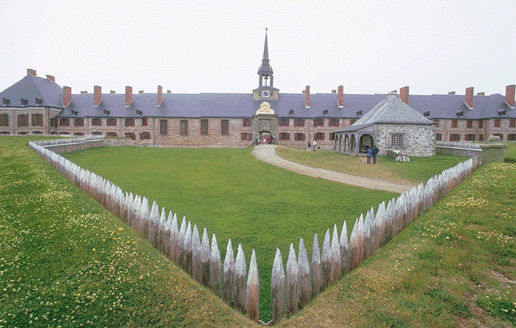

The economic recovery was very slow, but experienced unprecedented growth during the long period of peace from 1713 to 1744. To protect its fishing areas, territory and trade with the colony, France erected an imposing fortress in Louisbourg. The growth of agriculture resulted in surpluses which, from 1720, were exported to Cape Breton and the French West Indies. Canada’s territory included approximately 200 seigneuries. Due to a very high birth rate, the population increased substantially, which led to the creation of parishes. (See Population Settlement of New France.) The rules of mercantilism did not prevent the establishment of two major industries: foundry (see Les Forges Saint-Maurice) and royal shipbuilding (see Shipbuilding and Ship Repair).

In 1735, a dirt road linked Montreal to Quebec City for the first time. Despite this expansion of the colony’s economic foundations, fur still represented 70 per cent of its exports. And peace served to prepare for war. Eighty per cent of the colony’s budget — which did not even amount to the monies used for the king’s recreation — was used for military expenses. The construction of European-style fortifications used a great deal more of the budget than the strengthening of the network of alliances with the Indigenous nations.

Colonial society, influenced by the French elite who managed its destiny, modelled itself in the image of the mother country. It moved away from it, however, due to its small numbers and a radically different economic and geographic context. Nobles, members of the bourgeoisie, military officers, seigneurs, civil administrators, and traders became allies. Together, they formed a high society which was very reliant on favours from the colony’s authorities. Eighty per cent of the population, however, lived off the land and its products. Each generation produced new pioneers, who began anew to clear and settle the land, become used to the seasons, develop a new portion of the territory, and work with their neighbours. The importance of the land, of the family legacy, of economic independence all characterize the appropriation of this portion of America by the descendants of the French.

Conquest: France Leaves the English its Few Acres of Snow

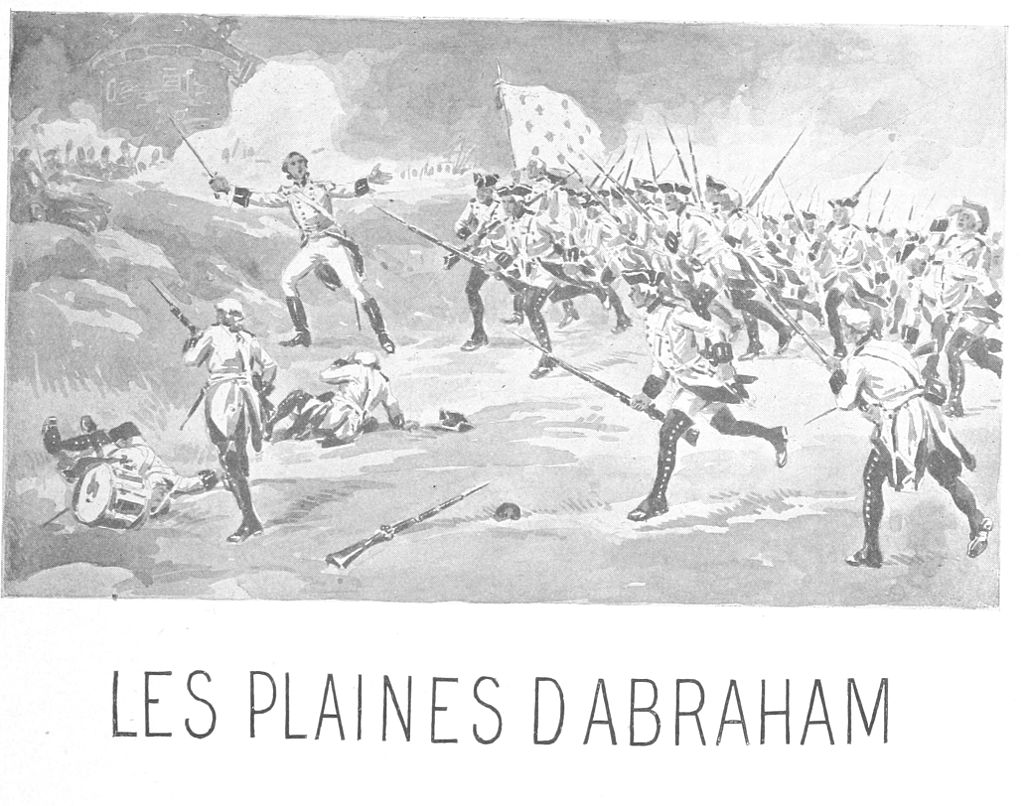

France felt, however, that New France cost a great deal, but brought little in return. The Seven Years’ War pitted Great Britain (which had become an aggressive sea power) against a France forced onto the defensive. It put the British colonies with their population of 1,500,000 against the scant 70,000 people who represented the mixed success of the French colonization endeavour in North America. Following resounding military successes due to a strategy adapted to the local conditions, France found itself on the defensive. On 13 September 1759, the troops commanded by General James Wolfe defeated those of the Marquis de Montcalm on the Heights of Abraham (see Battle of the Plains of Abraham), near Quebec City. The following year, Montreal fell in turn. (See Capitulation of Montreal.) Through the Treaty of Paris 1763, France ceded its colony to Britain. This essentially marked the end of France’s political power in America, but not of the French presence.

France has bequeathed America an invaluable legacy: the French-Canadian people, who will resist any attempts at assimilation and who will succeed in making themselves heard. Protected by their language, their religion and their institutions and living in a small, difficult to penetrate area, they have developed a way of life, social practices, and traditions all their own.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom