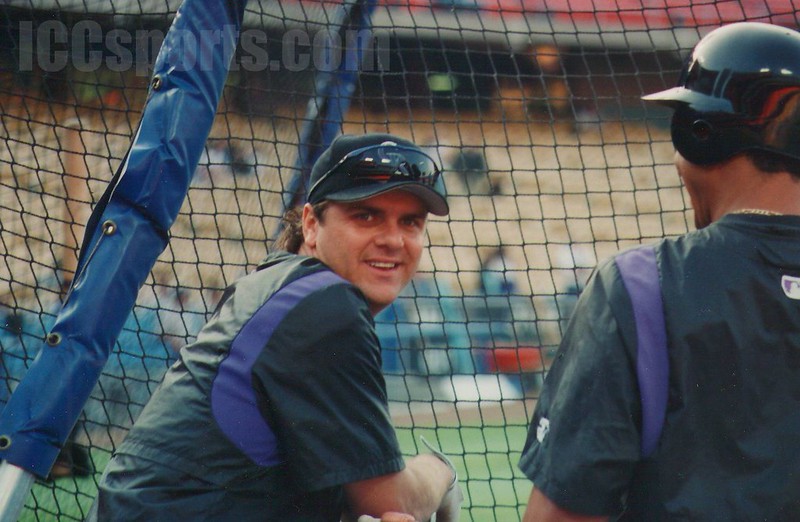

An undated photo of Larry Walker during batting practice with the Colorado Rockies.

His Colorado Rockies teammates are still out on the deep-green diamond, fielding grounders and taking batting practice, when Larry Walker saunters into the dugout at Tucson Electric Park. His baseball pants are grass-stained, and he's sweating from his

own turn in the batting cage. But he's skipping the last part of practice, which, truth be told, amounts to little more than standing around in the outfield, swapping jokes with the other veterans, while rookies and ball boys chase the fly balls. Truancy

is not a perk of being last season's Most Valuable Player in the National League. Walker had surgery in January to remove bone spurs from his right elbow, and after sitting out the early part of the Cactus League schedule to give the throwing arm a chance

to heal, he is easing into mid-season form - with the emphasis, apparently, on "ease."

That said, Walker is abusing his wrist. After grabbing a cup of water out of the dugout cooler, he has straddled a railing by the first row of seats and begun scribbling signatures for the throng of autograph-seekers who materialize seconds after he takes his post. "Thanks, Larry," a bespectacled kid gushes, offering a limp old mitt to be signed. "Nice glove," says Walker, who, given his own appearance, seems a connoisseur of the well-worn. A middle-aged woman in a Rockies jersey tells him it's her birthday. "I love you, Larry," she blurts as he autographs her baseball. "Happy birthday," he says, carefully avoiding eye contact. The line moves along and he is repeatedly asked if he can win another MVP, or hit .400 like he did for so much of 1997. One pock-faced teen wants to know if the hulking outfielder can beat last season's amazing home-run pace, when he clobbered 25 by mid-season. "Think you'll hit 30 by the all-star break?" the kid asks, waiting to get a baseball card signed. "Can't," says Walker, tongue firmly in cheek. "I'm already 31."

Plainly, the guy doesn't get it. Recent MVPs have been known to wear furs and diamonds, and affect the haughty air of royalty. Walker, meanwhile, is completely approachable, a big, loose-limbed lug with an easy smile and a quick wit. Maybe he hasn't been steeped in stardom for long enough to become a jerk - after all, the Maple Ridge, B.C., native only got serious about baseball in his late teens, when his dream of becoming a National Hockey League goalie stalled. Or maybe he's just naturally modest. Whatever, success has not expanded his hat size. "Walk's the same guy he's always been - he's still a clown," teases Mike Lansing, the Rockies' second baseman who also played with Walker in Montreal. "No way," says outfielder Ellis Burks, strolling by. "He's worse than ever."

Dubious testimonials aside, Walker is among the elite of a game that officially opened its 1998 season last week. Statistically, the slugging right-fielder was the best player in the majors last year, better even than Seattle megastar Ken Griffey Jr. - the American League MVP. In fact, only a handful of Hall of Famers, players such as Babe Ruth, Stan Musial and Hank Aaron, have ever had better seasons than Walker's. He hit .400 or above from April through the latter part of July, finished the season first in the National League with 49 home runs, second in batting average (.366) and third in runs batted in (130) - all while stealing 33 bases and winning a Gold Glove as the best defensive right-fielder in the league. Yet Rockies manager Don Baylor says Walker's best asset is neither his bat nor his glove. It's his grit. "When you're in a pennant race, he's the guy you want out there," says Baylor, a slow-talking Texan who won the 1979 American League MVP with California. "He likes to be the guy who's in the batters' box when the game's on the line."

Other than when pitchers throw fastballs at his head, the six-foot, three-inch Walker is slow to rile. But he did get upset when he was not named Canadian male athlete of the year in 1997. He's not mad at Jacques Villeneuve, who got the award for being the first Canadian to win a Formula One drivers' championship. But the title is "athlete" of the year, and Villeneuve, while undoubtedly athletic, won his title in large part because he had the best car on the circuit. (With a lesser ride this season, the Quebecer has not finished better than fifth in any race.) Walker's MVP was a first for Canada, too, and he alone hit those balls, ran those bases, made those catches, threw out those runners. Yet the majority of sports reporters and editors who vote on such things apparently found his accomplishments too pedestrian.

Walker had the off-season to get over it. He didn't. He says he usually doesn't care about individual honors, but this was different. "It's the one award that would have meant more to me than anything else," he says. After a pause, he adds: "I'm from Canada and I like to think I represent my country well. So it's frustrating - I got beat by a machine."

Sports were a big part of life in the Walker family. His father, Larry Sr., had played minor-pro baseball, and his brother, Cary, played goal for the major-junior New Westminster Bruins and was drafted by the Montreal Canadiens. Walker had hoped to play pro hockey as well, but he failed in tryouts with two major-junior teams. It was November, 1984, and Walker, then just 17, was struggling in Grade 12, too. "He wasn't doing that badly," Larry Sr. says. "But everything seems hard at that age." Walker wanted to quit school, and his dad warned him that he'd have to get a job. "We laugh about it now," the father says.

They can laugh because, exactly two days after quitting, Larry Sr. got a call from Bob Rogers, then the Montreal Expos' West Coast scout. Rogers had seen Walker play in a junior tournament in Kindersley, Sask., the previous summer, and wanted to know if he might be interested in a career in baseball, a game Walker says he then only played for the fun of it, to wile away summers on the Lower Mainland. The next day, Rogers flew to Vancouver, met with father and son, and left with Walker signed, for a $1,500 bonus, and assigned to a Class A team in Utica, N.Y.

According to his coach there, Gene Glynn, Walker barely knew the rules and had never faced a pitcher who could throw a real curveball. His 1985 stats were not promising, but Glynn liked his combination of speed and size, the way he would crash into the outfield wall to make a catch and tear the cover off the ball on the odd occasions when he made contact. "He had a real fire in him," Glynn says.

Walker proved to be a quick study. By 1989, he had earned a full-time spot with the Expos and became a key member of the 1994 team that was leading the majors when the players' strike cut short the season and cancelled the playoffs. "That sucked," he says. "We had the best team in baseball, and we had a good shot to win the World Series." Then the Expos, who regularly ship out all their expensive players for little in return, made no attempt to re-sign him, so he took the Rockies' offer - four years, $32 million.

Leaning back in his office chair at Hi Corbett, Baylor says he is amazed how far Walker has come, from Utica to most valuable player. "He has learned an unbelievable amount about the game," says Baylor. "Being Canadian has nothing to do with it. He's just a tremendously gifted player. It would not surprise me if he put together another MVP year."

He will have to stay healthy to do that, and his track record is not good. Walker has never played a full season, and missed all of 1988 following reconstructive knee surgery. He lost 60 games in 1996 after slamming into the outfield fence attempting to catch a long fly ball. He held on, but broke his left clavicle. Not surprisingly, he racked up his MVP numbers in the year when he played the most - 153 of 162 games.

He has withstood some blows to his personal life as well. His marriage dissolved soon after his daughter was born, and Brittany, now 4, lives with her mother, Christa Vandenbrink, in Maple Ridge. Does he get to see her much? "Not enough," he says. "She'll be in Denver for 20 days at the beginning of the season, and for a couple of weeks around the all-star break [in July]. After that, I don't know." He misses the rest of the family, too, although he arranges get-togethers when possible. He and his fiancée, Wisconsin native Angela Brekken, hosted his three brothers and their wives last Christmas for 10 days at Walker's winter home in West Palm Beach, Fla. Brittany came, too. "It was by far my best Christmas, to see my daughter get up and open her presents," he says. "It's a day I'll never forget."

Sitting on the dugout bench at Hi Corbett, Walker has an ice pack strapped around his right elbow, standard treatment after working out. In his other hand is the last quarter of a kaiser bun bulging with sliced meat and pickles, which he disposes of in a single efficient gulp. It is another one of those impossibly clear and sunny days in the desert, and Walker is trying to explain how he can miss so much of spring training and still be so sharp. "I don't make the game any harder than it is," he says. "A guy hits the ball, you catch it and throw it back in. It's a simple game if you just stick to the fundamentals and don't try to do too much."

There are a handful of other Canucks on big-league rosters, including Anaheim pitcher Jason Dickson of London, Ont., Oakland outfielder Matt Stairs of St. John, N.B., Toronto right-hander Paul Quantrill of Cobourg, Ont., and Seattle lefty Paul Spoljaric of Kelowna, B.C. But Walker is unquestionably Canada's greatest export to the American national pastime since Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins in the late-1960s and early 1970s. And for that, he has been richly rewarded. His contract is up at the end of this year and, with another good season, he could command $14 million annually in his next deal. He would prefer to stay in Denver - he likes the team, and loves the city. "It has everything," he says. "It reminds me of home, with the mountains, the snow, the climate, and the people are incredibly friendly." He would like to stay in the game, too, as a coach or a broadcaster, after he retires.

Before that happens, he has one main professional goal. "I want a World Series," he says. "I want to celebrate with the guys, to ride down 6th Avenue in Denver with my teammates and be able to say I was on the best team for one year." Personally, he hopes to arrange more time with Brittany. In the interim, he is keeping a journal. "She's going to be 5 in July, so I've started jotting things down for her," he says. "I should have done it a long time ago. I just write to her every day, and as she gets up there in age, she'll know what was going on with her father." If nothing else, that story will not be dull.

This article was originally published in Maclean's magazine on 13 April 1998. For our regular encyclopedia article on Larry Walker, please click here.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom