James Munroe Franklin, First World War soldier (born 12 October 1899 in Whitaker, Mississippi; died 8 October 1916 in France). Franklin, a private in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), was one of the first Black Canadians killed in action in the First World War. Franklin served in the 76th and 4th Battalions and was killed during the Battle of the Ancre Heights, part of the Battle of the Somme.

Family Background

James Munroe Franklin was born to Angeline Franklin and Walter Van Twiller Abraham Franklin in Whitaker, Mississippi, a village with a large Black American population. His father, Walter Franklin, was a farmer, jeweller, watchmaker and inventor who is credited with inventing the Original Keyboard Chromatic Harp (Patent number 2-137-160). Franklin was originally raised in the Baptist faith (his father converted to Judaism much later in life and earned the status of Rabbi).

In the late 1870s, southern states began to enforce segregation through what became known as the Jim Crow Laws. These laws were aimed at separating whites from “persons of colour” in schools and public transportation. The laws, which were in force until the 1950s, also enforced racial segregation in other public places, including restaurants, theatres, parks and cemeteries. This prompted a migration of Black Americans to the north and west, including the Franklin family, who left Mississippi and eventually crossed the Canadian border in 1901, settling in Hamilton, Ontario. Five years after the family moved, Franklin's mother, Angelina, passed away due to complications in pregnancy.

Orphanage

James Franklin was just seven years of age when his mother died. Shortly after, his father placed him in Hamilton's Stinson Street Boys’ Home, an orphanage. As in many orphanages at the time, the majority of the residents were probably “half orphans,” boys like Franklin with one living parent. While he lived in the Boys’ Home, his father married an Irishwoman, Sarah Margaret Johnson. They had eight children, but Franklin remained in the orphanage.

In 1911, the Stinson Street Boys’ Home housed 79 boys ranging in age from 4 to 14. It was a tough life, especially for the few Black children. Erasmus Toliver was a half orphan who already lived at the school when Franklin arrived. In later conversations with author Nerene Virgin, he described the Stinson Home as "an awful place" where the administrators and staff referred to the children as “inmates” and served them unpalatable meals, including maggot-filled porridge. According to Toliver, only three Black children lived in the institution during his time there (one of whom was the young James Franklin). Toliver recalled that the darker skinned boys were often treated with disdain and were sometimes beaten and belittled. Franklin would remain here until age 14.

The “inmates” were schooled in the facility by a teacher on staff. According to Toliver, once the boys reached age 14, they were usually apprenticed to a local business. In 1913, Franklin boarded with a widow named Ellen Henrietta Bryant-Johnston and her children Ellen, Charles and William, who lived near the Parke and Parke drugstore. Charles was only a few months older than Franklin and the boys were like brothers. Charles worked as a teamster and Franklin took a job as a clerk and messenger at Parke and Parke, which at the turn of the 20th century was one of Hamilton's most prominent businesses. Parke and Parke drugstore was owned by two brothers, George and Walder Parke. Walder had four sons, all of whom volunteered for service as officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) at the beginning of the First World War.

With the CEF

In 1915, James Franklin decided his future was with the

CEF and enlisted under one of Walder Parke’s sons, Harold, who was then commanding officer of the 91st Canadian Highlanders. (Harold Parke signed Franklin’s

attestation papers as both the witness and commanding officer.)

Franklin was one of the first Black Canadians to enlist in the CEF; although many others attempted to enlist, there was considerable resistance to the idea among some commanding officers, particularly in the early stages of the war. Some white volunteers

also refused to serve with Black soldiers. (See Black

Volunteers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.)

According to Franklin’s attestation papers, he stood 5 feet 7 inches tall when he enlisted in the CEF on 26 July 1915. He was only 15 or 16 at the time of enlistment, too young for military service. However, he claimed that he was older, listing his year

of birth as 1897 when, according to census records, he was born in 1899 (an article in the Chicago Defender also supports this later birthdate).

When Franklin enlisted, the 91st Canadian Highlanders were recruiting men for service with the 76th Overseas Battalion. Franklin and 76 other soldiers from the 91st were therefore assigned to the battalion’s “B” Company, along with their commanding officer,

Harold Parke.

The 76th battalion boarded the Empress of Britain in Halifax on 23 April 1916 and sailed to Europe, disembarking in Liverpool, England, on 5 May 1916. On 28 June 1916, Franklin was transferred to the 4th battalion and was deployed for

combat in France.

Death at Ancre Heights

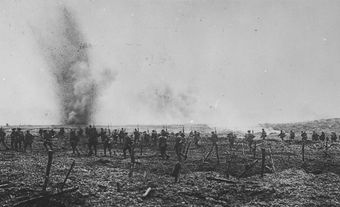

James Franklin died only months after arriving in Europe, killed on 8 October 1916 during the Battle of the Ancre Heights, part of the Battle of the Somme.

During the battle, Canadian troops advanced on German positions in what was known as the Regina Trench. However, the Canadians were not able to hold their position. According to Colonel William Ray of the 4th Battalion (Franklin’s commanding officer), this was due in large part to the “impossibility of getting up supplies or reinforcements by day.” In his military diary, Ray explained that penetrating the German barbed wire had caused a greater delay than anticipated and had depleted the Canadian supply of bombs.

The supply of bombs gave out and could not be renewed … practically the whole of our first objective had to be cleared by bombing owing to the wire preventing a direct attack. This was not anticipated, and consumed a large number of the Reserve Bombs.

An attempt was made during the morning [of 8 October 1916] to get a carrying party with bombs across the open. The party got there with 12 casualties, and no further attempts were made.

It is very likely that Franklin was part of the supply party that was attacked, even though his name does not appear in Ray’s diary. According to family and community oral history, Private Franklin was ordered to load up his pack mule and carry forward combat supplies on that fateful day. Like his fellow soldiers, he was vulnerable to snipers, artillery and machine gun fire. According to an article in the Chicago Defender , Franklin and his mount were “literally blown to pieces” by a "huge grandmother shell" that exploded near them. Franklin’s battalion reported that he went missing on 8 October, and later confirmed his death.

Legacy and Recognition

According to his military will, Franklin left $250 to St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Hamilton; Franklin was actively involved in the church, serving as librarian (1914) and assistant secretary (1915) as a teenager. He also left $250

to “Mrs. E.H. Johnston,” the woman he lived with for two years before he enlisted with the CEF. There was clearly a strong bond between Franklin and the Bryant-Johnson family (who were heavily involved in the church as well).

About a month after learning that Franklin was “missing in action,” Charles Bryant volunteered for service with the No.

2 Construction Battalion — perhaps with the thought of finding his close friend. Like Franklin, it seems that Bryant falsified his age to enlist. He sailed overseas on 28 March 1917 with the rest of the battalion but died of meningitis less than

four months later in France. The congregation of Stewart Memorial Church in Hamilton (formerly St Paul’s AME Church) continues to honour the sacrifice of Franklin and Bryant, as well as that of Mark Graham, a member of the congregation who was killed

in Afghanistan in 2006.

James Franklin’s name is inscribed on page 88 of the First

World War Book of Remembrance, which is housed in the Memorial Chamber in Peace Tower, part of the Parliament

Buildings in Ottawa. His name is also engraved on Canada’s Vimy Memorial in France. (See also Monuments

of the First and Second World Wars.)

Franklin’s story has been recognized in the United States as well. In a 1918 newspaper article, the Chicago Defender reported that "Franklin was a self-raised, brave, young man and the first Canadian of his Race to die upon the fields

of France.”

In 2015, the Mississippi Armed Forces Museum constructed an exhibit to honour his service. Museum director Chad Daniels wrote to researcher Alan Smith that “Private Franklin’s story is inspirational as an example of loyalty and valour during times of pronounced prejudice and injustice."

Acknowledgements

A great deal of collaboration and research was required to complete this biography. Our thanks to William Huling, PhD; Patricia Grizzle Huling, PhD; Evelyn Ali; Royetta Phillips; Nerene Virgin; Alan Smith; Molly James; Anita Toliver; Douglas Smith, PhD; and curator Stan Overy at The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry Heritage Museum.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom