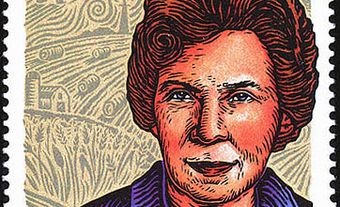

Isabel Skelton (née Murphy), historian and author (born 9 July 1877 in Antrim, Ontario; died 22 August 1956 in Montreal, Quebec). The author of literary criticism, historical articles, three historical and biographical works and three high school history textbooks, Skelton was one of the first Canadian historians to analyze the role of women as a group in Canadian social history.

Early Life and Education

Isabel Murphy was the eldest of the three surviving children of Mary Jane “Jeannie” Holliday, a teacher, and Alexander Murphy, a farmer, school trustee, postmaster, township clerk and justice of the peace. She attended Arnprior District High School and then began studies in 1897 at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, where she majored in English and history. She earned a master of arts degree and received the gold medal in history in 1901. As a student at Queen’s University, she was treasurer of the Levana Society for university women.

Marriage

On 16 August 1904, Isabel Murphy married Oscar Douglas Skelton at her family’s farm in Antrim. The pair met when they were students at Queen’s University. They spent five months travelling in the United Kingdom and Europe for their honeymoon before moving to the United States, where Oscar was a PhD candidate at The University of Chicago. The Skeltons shared intellectual interests and political views — both believed Canada needed greater autonomy in foreign policy from the United Kingdom. As authors, they encouraged and edited each other’s work. During Oscar’s frequent absences from home for academic research and civil service, he wrote affectionate letters to his wife, calling her “Iso” and “Darling Mine.” She also wrote to Oscar, but her letters did not survive. She was frustrated, however, with the heavy burden of domestic responsibilities that accompanied marriage and motherhood, fearing that she would not have any time to write and would become “a pitiful example of a woman who gives up her own work and washes dishes instead.”

Children

Isabel and Oscar Skelton had three children: Douglas Alexander “Sandy” (1907–50); Herbert Hall (1909–87); and Sheila Isabel Halliday (1918–98). Her health suffered during her pregnancies. She experienced hair loss, tooth decay and varicose veins before and immediately after Sandy’s birth. Oscar’s frequent absences from home meant that she did much of the child rearing, balanced with her own writing, managing the Skelton household and her social responsibilities in support of her husband’s career. She reflected later in life, “We did not bring to the boys attention and ourselves enough. I have given more to Sheila, and she is a joy.”

Queen’s University

In 1909, Isabel and Oscar Skelton moved to Kingston when he became the John A. Macdonald Professor of Political Science and Economics at Queen’s University. He later served as the dean of arts from 1919 to 1925. She was active in women’s organizations on campus, including the Queen’s University Alumni Association. She became president of the Women’s Canadian Club of Kingston in 1915. In 1922, she was the only female member of the Canadian delegation to the Pan-American Conference in Rio de Janeiro.

At Queen’s University, she presented and published articles about literature and history, including studies of British and American female novelists Mary Ward and Edith Wharton for Westminster Magazine in Toronto in 1910. She also advocated for women’s suffrage in Canada, writing an article for The Canadian Magazine that stated women voters might achieve legislative “justice in regard to property rights, marriage and divorce and the guardianship of their children.”

Historical Scholarship

As a historian, Isabel Skelton questioned the dominance of political biography in Canadian historiography, which focused on the achievements of “great men” and a few “great women” considered heroines, such as Laura Secord. Skelton instead championed the inclusion of material culture, literature and philosophy and the domestic sphere in the writing of history.

In 1915, Skelton proposed a book about the history of Canadian women for the Chronicles of Canada series to be published by Robert Glasgow of United Editors Limited. In the section on New France, she presented a series of short biographies of famous women, such as Marie Hebert, Marie de l’Incarnation and Marie-Madeleine Jarret de Verchères. The chapters on Loyalist women and female settlers in Upper Canada, however, considered women as a group and the impact of their domestic activities on the development of Canadian society and nationhood.

In 1916, Glasgow moved to the United States and Skelton bought back the rights to her manuscript. Her book The Backwoodswoman: A Chronicle of Pioneer Home Life in Upper and Lower Canada was eventually published by The Ryerson Press in 1924. Skelton’s research about Canadian women’s history did not have an immediate impact on scholarly histories of Canada, but her work informed the writing of Canadian school textbooks, including University of Toronto historian George Brown’s Building the Canadian Nation (1942).

Skelton’s second book, The Life of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, was published in 1925 — the centenary of McGee’s birth — and received favourable reviews, especially in Ireland and the United States. In Canada, Skelton’s focus on McGee’s literary endeavours and ideas of cultural nationalism attracted some critiques from reviewers who expected a traditional political biography focused on his time as a Member of Parliament before his assassination in 1868.

Ottawa

In March 1925, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King appointed Oscar Skelton as undersecretary of state for external affairs, and the Skelton family moved to Ottawa. Isabel Skelton was unhappy with the move, which separated her from her scholarly network at Queen’s University. The couple disagreed over where they should live in Ottawa, with him favouring a larger house in Rockcliffe Park that reflected his prominent status in the civil service and her preferring a smaller home that would require less upkeep and allow more time for research and writing. She wrote in her diary in August 1925, “The confounded houses [are] between us, and I feel it quite impossible to discuss the question.” His wishes prevailed. She supervised the renovation of the house they named “Edgehill.”

In Ottawa, she was active in Girl Guides of Canada and St. George’s Anglican Church and gave public addresses about history and literature for women’s organizations and educational institutions, such as the Ottawa Ladies’ College. She wrote three short Canadian history textbooks for students concerning Thomas D’Arcy McGee, Jean de Brébeuf and Issac Jogues, respectively, for The Ryerson Press in the 1930s. During her husband’s time in the Department of External Affairs, she travelled occasionally with him to the United Kingdom and Europe, attending the coronation of King George VI with her husband and daughter in 1937.

Later Life

Oscar Skelton died from a heart attack while driving in downtown Ottawa in 1941. The widowed Isabel Skelton moved from Ottawa to Montreal to live closer to her son Herbert and his wife, Daisy May McCracken. She continued to be active in public life during the Second World War, serving with other authors and scholars on the Committee on Co-operation in Canadian Citizenship, an organization intended to connect new Canadians with patriotic efforts during wartime. On this committee, she recommended Canadian history books to new Canadians and wrote pieces about Canadian historical figures, such as John Graves Simcoe. She devoted her later years to writing her last book, A Man Austere: William Bell, Parson and Pioneer (1947), a study of a key figure in the development of the Presbyterian Church in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom