The six “Historical Thinking Concepts” were developed by The Historical Thinking Project, which was led by Dr. Peter Seixas of the University of British Columbia and educational expert Jill Colyer. The project identified six key concepts: historical significance, primary source evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives and ethical dimensions. Together, these concepts form the basis of historical inquiry. The project was funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage and The History Education Network (THEN/HiER). Seixas and Tom Morton published a book, The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, that expanded on these concepts.

The six “historical thinking concepts” are: historical significance, primary source evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives and ethical dimensions. Together, these concepts form the basis of historical inquiry.

(Courtesy Historical Thinking Project)

Establish Historical Significance

This concept asks us to consider what events we choose to remember and why. Since history is so vast, we cannot possibly remember everything. Why is a particular event important? Who decides what is significant, and how might their perspective on this question differ from our own?

Use Primary Source Evidence

Historians use evidence from sources to support their statements and conclusions. This is a key part of crafting believable and trustworthy narratives (or accounts). Does the author provide references to primary sources? Can I find primary source evidence to fact-check their claims? How does the availability of primary sources shape what we remember and what we decide is historically significant? (See Historical Sources.)

Identify Continuity and Change

We are drawn to change as a marker of historical significance. This is particularly true for major upheavals like war and revolutions. Yet, this historical thinking concept asks us to consider continuity as well. The absence of upheaval and maintenance of continuity can also be historically significant. For example, what does it mean that the Canadian rail system has gone largely unchanged for decades while other nations transitioned to electric trains?

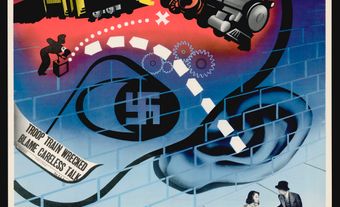

Analyze Cause and Consequence

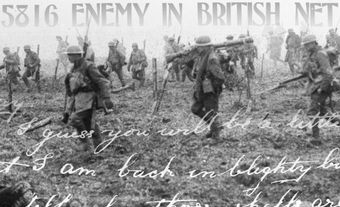

When discussing a historical event, you should understand the causes of the event. Why did it happen? When considering this question, it is important to be able to explain why a certain event occurred in the way that it did. Why did the First World War begin in 1914, not 1912 or 1917? Then we can assess the lasting consequences of an event. (See also First World War Education Guide.)

A Canadian solider looking through a shell hole in the Cathedral in Ypres, Belgium. November, 1917.

Consider Historical Perspectives

Make sure you understand the social, cultural, intellectual and emotional contexts in which an event occurred. It may be easy for us, with the benefit of hindsight, to see the “right” course of action, but it may not have been obvious then.

Understand the Ethical Dimensions of Historical Interpretation

Historical figures often do not share our viewpoints, values or guiding principles. Historians must understand the ethical framework and expectations in which historical figures operated and resist applying modern ethical standards to historical events.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom