The following article is part of an exhibit. Past exhibits are not updated.

The history of the Canadian film industry has been one of sporadic achievement accomplished in isolation against great odds. Canadian cinema has existed in an environment — namely, the cultural and industrial shadow of Hollywood — where access to capital for production, to the marketplace for distribution and to theatres for exhibition has been extremely difficult.

Despite this, Canadian cinema has developed a vital, unique and diverse identity, and Canadian filmmakers have come to punch well above their weight in international cinema; Québec, in particular, has cultivated a strong domestic industry and produced several directors who have found considerable success in Hollywood.

Here are some of the great achievements, along with some of the obstacles that have helped define the Canadian film industry's underdog character.

Pioneering Years

27 June 1896 — The first public screening of a film in Canada takes place at the Palace Theatre at 78 St. Lawrence Boulevard in Montréal, where two operators present the Lumière Cinématographe.

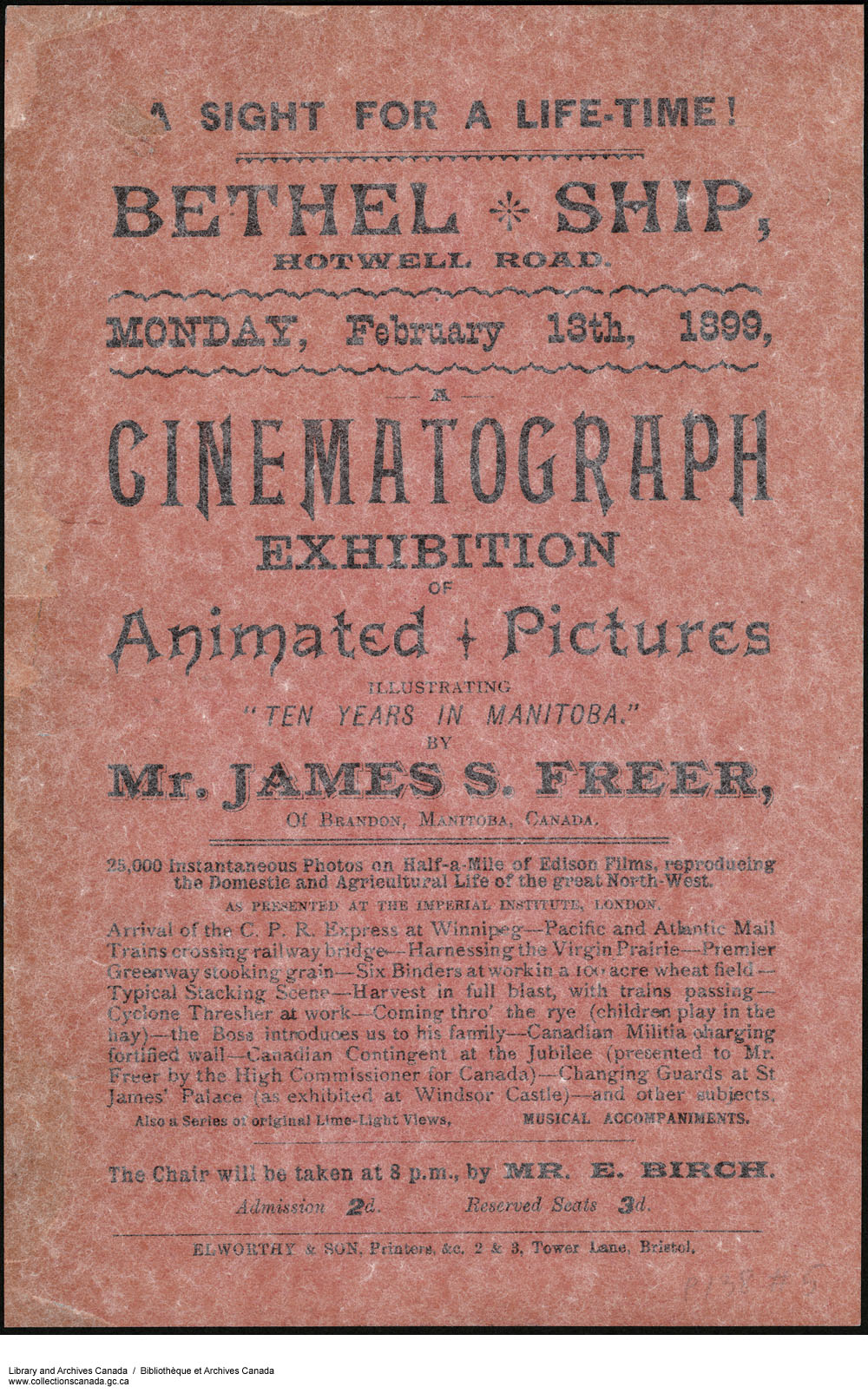

1897 — Manitoba farmer James Freer makes Canada’s first films. In 1899, he tours England with his “home movies,” which depict life on the Prairies. They are so successful the federal government sponsors a second tour in 1902.

1903 — Léo-Ernest Ouimet establishes Canada's first film exchange in Montréal. He opens Montréal’s first theatre in 1906, followed in 1907 by the largest luxury theatre in North America.

1903 — The first fictional drama made in Canada, the 15-minute-long Hiawatha, The Messiah of the Ojibway, is produced by the Canadian Bioscope Company to encourage British immigration to Canada.

1913 — Bioscope also makes the first Canadian feature, Evangeline (1913), based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem about the expulsion of the Acadians. It is a critical and financial success.

American Exhibition Monopoly

1918 — The Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau becomes the first national film production unit in the world. But it never attempts to develop a domestic film production industry. The bureau’s first director said that Canada “had no more use for a large moving picture studio than Hollywood had for a pulp mill.”

1919 — Back to God’s Country, produced by Ernest Shipman and starring his wife, Nell Shipman, becomes an international hit, earning a 300 per cent profit.

1922 — The Canadian Motion Picture Distributors Association (CMPDA), a branch office of the Hollywood studios, is formed. The association begins to include Canadian theatre receipts in US box office tallies.

1923 — Famous Players, owned by Paramount Pictures, buys all 53 of the Canadian-owned Allen Theatres and seizes control of the Canadian exhibition market.

1923 — The Ontario Motion Picture Bureau buys Trenton Studios to produce films “for the purpose of preserving Canadian traditions.” In an opening speech, the provincial treasurer notes that “Not one per cent of the pictures shown in Canada… are Canadian made.”

From Quota Quickies to Cooperation

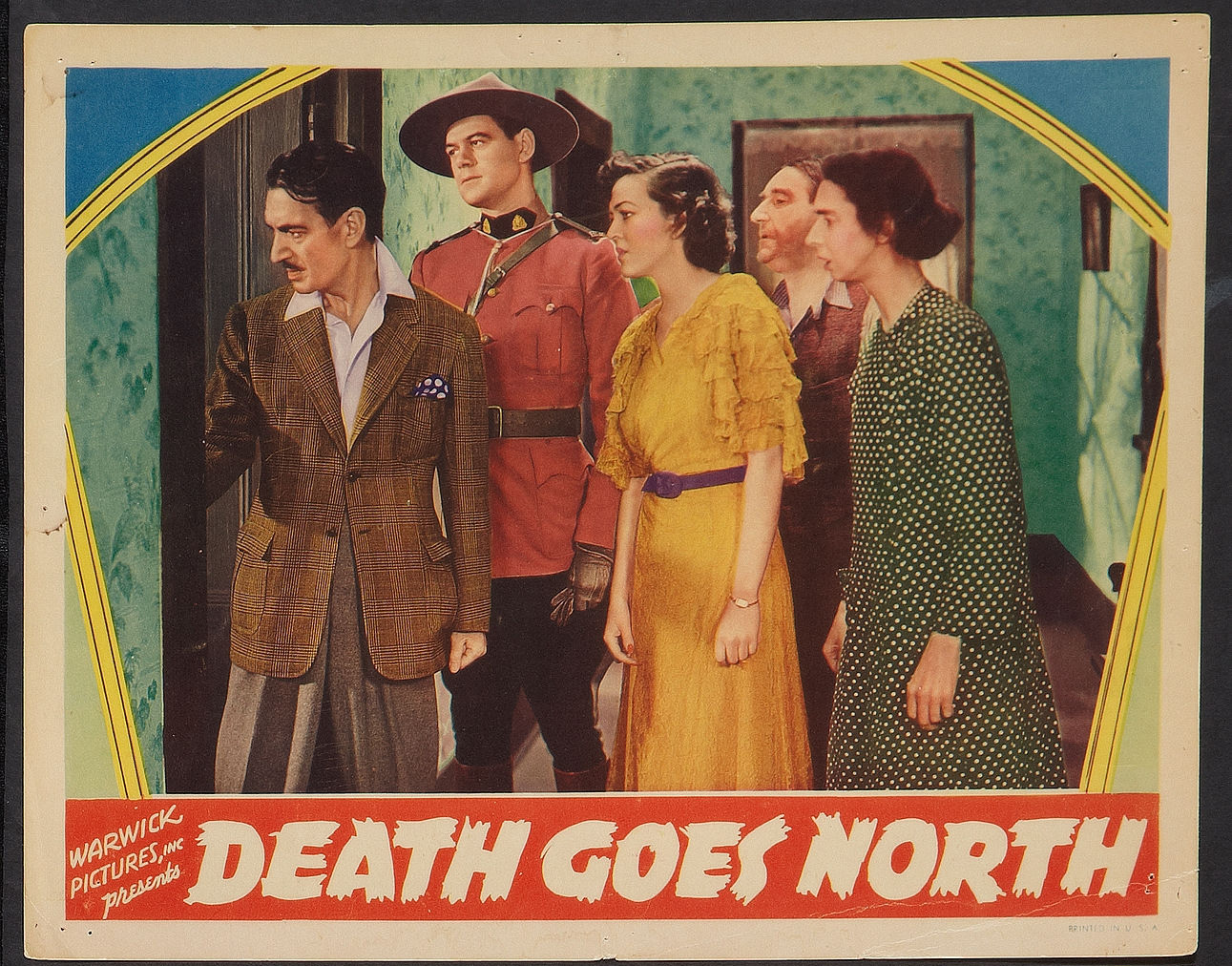

1927–37 — After the UK stipulates that 15 per cent of films shown in Britain must be of Commonwealth origin, 22 low-budget “quota quickies” are produced in Canada by American-financed companies.

1930s — Priests Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx make ethnographic films about rural Québec that are considered early documentaries.

1939 — The National Film Board (NFB) is created, and John Grierson — who coined the term documentary in 1926 — is named its first film commissioner.

1947 — Under pressure to impose a quota or tariff on Hollywood films exhibited in Canada, the federal government asks the CMPDA to invest some of its box-office profits in Canadian production facilities. Instead, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) proposes the Canadian Cooperation Project. Hollywood studios agree to shoot films on location in Canada, include references to Canada in Hollywood movies, and distribute NFB films in the US — all in exchange for maintaining Hollywood’s exhibition monopoly in Canada.

Exodus and Excellence

1953 — NFB animator Norman McLaren, Canada’s most honoured filmmaker, wins an Academy Award for his short film Neighbours (1952).

Late 1950s — Sidney Furie, a young CBC writer, directs two low-budget films— A Dangerous Age(1957) and A Cool Sound from Hell (1959) — which attract international critical attention but are completely ignored in Canada. Furie immigrates to Britain, where he tells the press, “I wanted to start a Canadian film industry, but nobody cared.” During this period, directors such as Norman Jewison, Arthur Hiller and Ted Kotcheff also leave Canada to pursue their careers elsewhere.

Late 1950s & early 1960s — Emboldened by the creation of a French production unit at the NFB, filmmakers such as Pierre Perrault, Gilles Carle, Claude Jutra, Michel Brault, Gilles Groulx and Denys Arcand produce works of tremendous importance to the Quiet Revolution and the development of direct cinema.

Waving Hello

Early 1960s — Jutra’s À tout prendre (1963), Groulx’s Le Chat dans le sac (1964) and Carle’s La Vie heureuse de Léopold Z. (1965) are heralded as the first fiction films to truly speak to the Québécois experience.

1963 — Independent filmmaker Budge Crawley produces Amanita Pestilens, the first Canadian colour feature, the first film shot in English and French, and the film debut of Geneviève Bujold. It is never released theatrically.

1964 — Nobody Waved Good-bye marks an important first step for the still-nascent English Canadian feature film industry. Hired by the NFB to make a short documentary on juvenile delinquents, Don Owen expands the project into a narrative feature about teenage rebellion, which becomes a hit with US critics.

1967 — Michael Snow’s Wavelength premieres, and quickly becomes one of the most important and influential works in the history of experimental cinema. In 2001, the Village Voice ranks it No. 85 on its list of the 100 best films of the 20th century.

Fund Times

1967 — The federal government creates the Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC) to provide government financing for narrative feature film production. It is renamed Telefilm Canada in 1984, when its mandate is broadened to include television.

1970 — Don Shebib’s landmark film Goin’ Down the Road becomes an artistic and commercial success in Canada and internationally.

1971 — Claude Jutra’s Mon oncle Antoine, based on an autobiographical screenplay by Clément Perron, wins more than 20 international prizes and eight Canadian Film Awards. It goes on to top lists of the greatest Canadian films for decades.

1974 — The federal government begins to allow investors to write off 100 per cent of their investment in Canadian feature films, resulting in a massive increase in Canadian production and marking the beginning of the tax-shelter era. Production in Canadian feature films increases from three in 1974 to 77 in 1979. However, many of the films never receive distribution.

Exhibit Eh

1971 — IMAX Corporation opens the first permanent IMAX® theatre at Ontario Place.

1971–75 — Support for a Canadian exhibition quota intensifies but never materializes. Instead, in 1975, Famous Players and Odeon Theatres volunteer to devote four weeks per theatre each year to Canadian films, and invest a minimum of $1.7 million in their production. Compliance was lukewarm at best and evaporated within two years.

1975 — Saturday Night magazine runs a scathing review of David Cronenberg’s Shivers. “If using public money to produce films like this is the only way that English Canada can have a film industry,” it says, “then perhaps English Canada should not have a film industry.” A furious debate is sparked in the House of Commons over the use of tax-payer dollars to fund films.

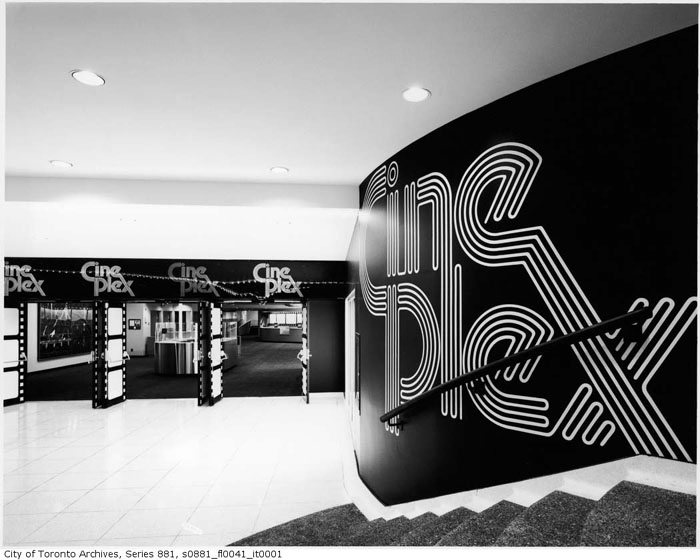

1979 — In Toronto, Nat Taylor and Garth Drabinsky open the world’s biggest multiplex, with 18 screens.

1987–88 — Legislation introduced by the Mulroney government that would have curtailed American distribution in Canada is abandoned following fierce opposition by the MPAA.

Catching the Wave

Mid-1980s to mid-1990s — The Ontario Film Development Corporation supports such filmmakers as Atom Egoyan, Bruce McDonald, Peter Mettler, Ron Mann, Patricia Rozema, John Greyson, Jeremy Podeswa and Don McKellar, resulting in the Toronto New Wave.

1987 — Rozema’s ultra-low-budget debut feature, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, wins a major prize at Cannes and becomes one of the most profitable Canadian films ever made, grossing more than $6 million worldwide.

1986 and 1989 – Denys Arcand revitalizes the Québec film industry when Le décline de l’empire américain (1986) and Jésus de Montréal (1989) earn Oscar nominations.

1987 and 1992 — Jean-Claude Lauzon takes the Canadian film industry by storm with two highly acclaimed feature films: Un zoo la nuit (1987) and Léolo (1992). Lauzon dies tragically in 1997.

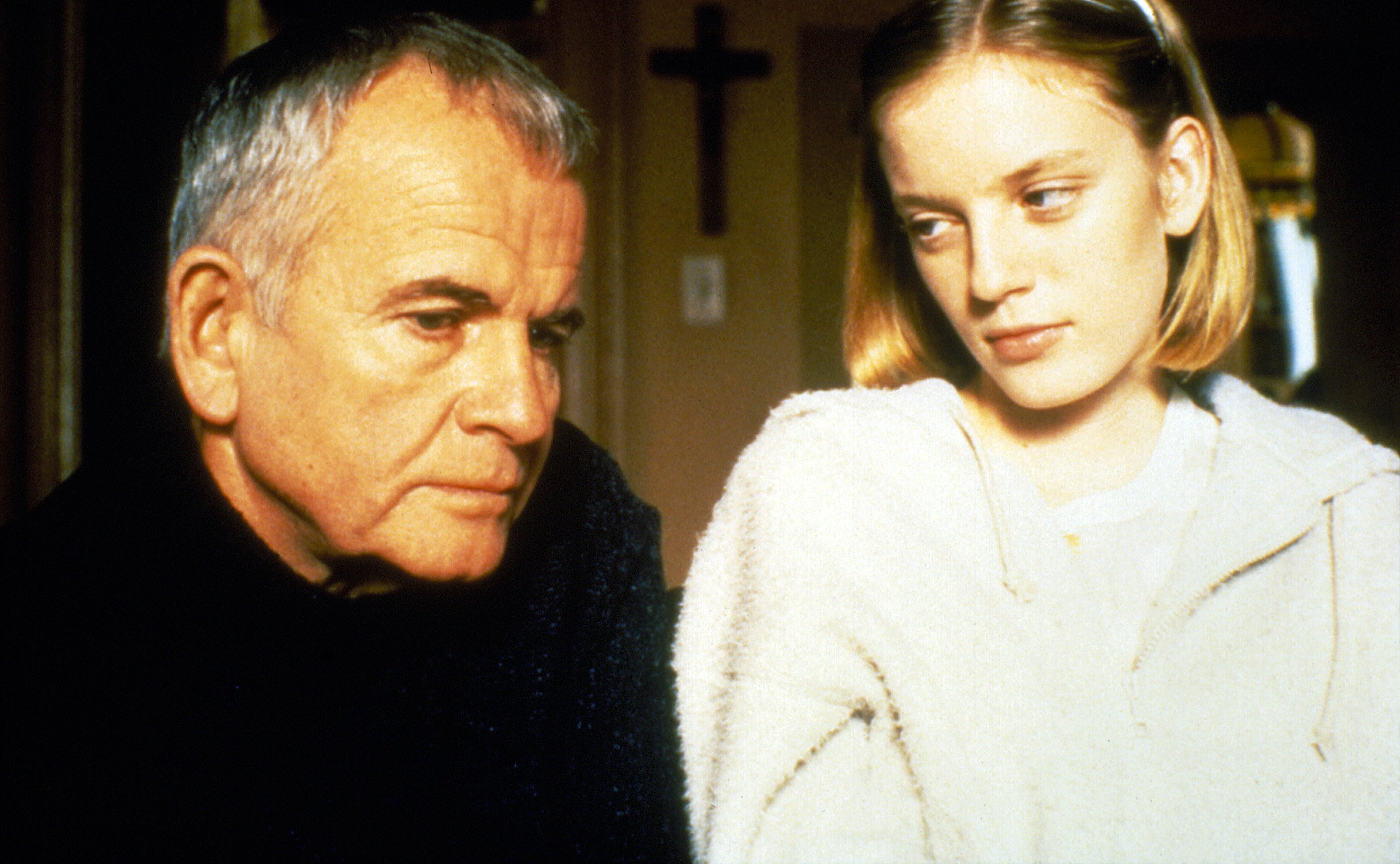

1997 — Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter wins three major awards at Cannes and goes on to receive Oscar nominations for adapted screenplay and best director — the first for a Canadian director.

Running Down an Audience

2000 – With Canadian films accounting for about two per cent of the country’s box office, the federal government’s new feature film policy sets a target of capturing five per cent of the domestic box office in five years.

2001 — Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) (2001) becomes the first Inuktitut-language feature film ever made. It wins numerous awards worldwide, including best first feature at Cannes and five Genie Awards. In 2015, it is named the best Canadian film of all time.

2004 — After earning two previous Oscar nominations, Denys Arcand wins for Les Invasions barbares (2003).

2005 — Canadian films capture 4.9 per cent of the Canadian box office, but only because Québec films account for a quarter of the province’s box office. English-language films languish at 1.5 per cent nationally.

2005 — Sarah Polley and Don McKellar lobby the federal government for dedicated screen time for Canadian movies and trailers in theatres and on TV. No action is taken.

2007 — Bon Cop Bad Cop (2006) becomes the highest-grossing Canadian film of all time, earning more than $13 million domestically.

Vive le Québec… à Hollywood?

2005 — Jean-Marc Vallée’s C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005) becomes a box office hit in Canada and France.

2008 — Sarah Polley becomes the first woman to win the Genie Award for best director, for her debut feature, Away from Her (2006). Her screenplay adaptation of the Alice Munro short story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” also receives an Oscar nomination.

2010–12 — Three Québec films are nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar three years in a row: Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies (2010), Phillipe Falardeau’s Monsieur Lazhar (2011) and Kim Nguyen’s Rebelle (War Witch) (2012).

2013–Present — Vallée, Villeneuve and Falardeau become hot commodities in Hollywood with movies such as Dallas Buyers Club (2013), Sicario (2015) and The Bleeder (2016), respectively.

2009–15 — Xavier Dolan makes four feature films before turning 25. The first, J’ai tué ma mère (2009), wins three prestigious awards at Cannes, as well as Best Screenplay and Best Film at the Gala du cinéma québécois. His fifth, Mommy (2014), ties for the Cannes Jury Prize and wins nine Canadian Screen Awards.

Fund Times

1967 — The federal government creates the Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC) to provide government financing for narrative feature film production. It is renamed Telefilm Canada in 1984, when its mandate is broadened to include television.

1970 — Don Shebib’s landmark film Goin’ Down the Road becomes an artistic and commercial success in Canada and internationally.

1971 — Claude Jutra’s Mon oncle Antoine, based on an autobiographical screenplay by Clément Perron, wins more than 20 international prizes and eight Canadian Film Awards. It goes on to top lists of the greatest Canadian films for decades.

1974 — The federal government begins to allow investors to write off 100 per cent of their investment in Canadian feature films, resulting in a massive increase in Canadian production and marking the beginning of the tax-shelter era. Production in Canadian feature films increases from three in 1974 to 77 in 1979. However, many of the films never receive distribution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom