The Greek word katholikos means "general" or "universal." It refers most commonly to the Christianity that is in communion with the pope and the Church of Rome, that is, the beliefs and practices of a Catholic Church. The modern ecumenical movement often refers to all Christians as sharing in the church's Catholicism, which is derived from the universal headship and reign of Christ. According to the 2021 census, 10.9 million Canadians (29.9 per cent) identified as Catholic.

Origins

St. Ignatius of Antioch (died around 110 AD) was the first person known to have referred to the "Catholic church." St. Vincent of Lerins (5th century) later defined the Catholic faith as "that which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all." In the church's belief, God is the creator and father of all, and God the son (Christ) has a universal kingdom, the church. The earliest Christian churches, established amid great linguistic, cultural and ethnic diversity, regarded themselves as constituting one holy Catholic church of Christ.

The Roman Catholic Sacraments

The Roman Catholic Church recognizes seven religious acts, or sacraments: baptism, normally of infants; confirmation; the Eucharist (communion), celebrated centrally in the mass (public worship) and offered only to the baptized; confession, which involves the petitioner's penance and absolution by a priest; ordination (admission to one of three clerical ranks); marriage; and unction (anointing), normally administered only if the recipient is seriously ill or death is imminent.

Government of the church is by a hierarchy of bishops, priests and deacons under the authority of the pontiff (supreme priest), or pope, who is bishop of Rome and the head of the Catholic Church. The government of the church is in the Vatican in Rome. Cardinals are archbishops or bishops appointed by the pope, and upon the death of a pope they are responsible for electing the next pope. Each bishop is the head of a diocese and is responsible, among other things, for ordaining new priests. Priests are responsible for their individual parishes and congregations. The doctrine of apostolic succession holds that the spiritual authority vested in the apostles by Christ has descended in unbroken succession to the present pope, bishops and priests, who possess this authority in varying degrees. All clergy must be male. The church has numerous Christian religious communities of both genders; members commit themselves to chastity, as do priests and bishops of the Western rite.

Early History of the Roman Catholic Church in Canada

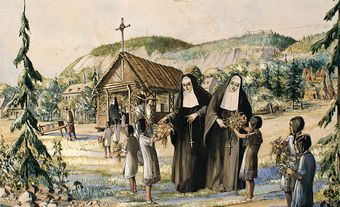

Roman Catholicism came to what is now Canada with the first European explorers but was slow to establish itself. Whether Jacques Cartier really was accompanied by chaplains in 1535, Catholicism did not take hold until Samuel de Champlain persuaded the French church to act on his pro-settlement campaign. Circumstances favoured the missionary spirit that led to a Canadian Catholic Church. These included the interest of the papacy and the religious orders in the New World; the end of the religious wars in France; the reforms following the Council of Trent, which regenerated the French church; and the enthusiasm of the devout for missions abroad. Supported by noble benefactors and the French clergy, members of the Récollet Franciscan order established themselves in Quebec in 1615, followed in 1625 by the Jesuits. The missionaries went home to France during the English occupation of 1629-32, but then returned in force (although, by order of Cardinal Richelieu, only the Jesuits were permitted to resume their work).

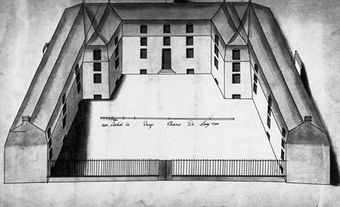

This young Canadian church was devoted almost entirely to evangelizing Indigenous peoples. Without neglecting the increasing number of settlers in New France, the Jesuits (and later the Sulpicians) concentrated on living with the Indigenous people. The accounts of their labours, published in the Jesuit Relations, helped them to hold the interest of Catholics in France. Generous donations funded the Jesuit college (1635); the Sillery reserve (1637); the Ursuline Convent school (1639) run by Marie de l'Incarnation; the Hôtel-Dieu (1639); and Ville-Marie (1642), where the same institutions as those in Quebec were established. The church supported the colony and was dominant even in politics, with the Jesuit superior often supplanting the governor.

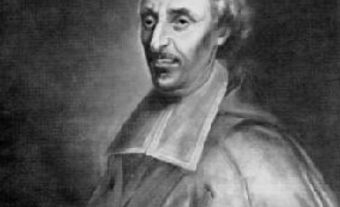

Everything had changed by the 1650s. In 1648-50 the Iroquois destroyed Huronia, and with it the Jesuits’ most promising mission, Ste Marie Among the Hurons. Thereafter the Jesuits worked in scattered missions among the Indigenous peoples, but they had to devote increasing attention to the growing French population. The church received its first prelate (senior clergyman) in 1659. Though François de Laval was only vicar apostolic (i.e., acting bishop where no hierarchy exists), he had sufficient jurisdiction to co-ordinate the establishment of the necessary institutions, including the Séminaire de Québec. After New France's reorganization in 1663 as a royal colony, the church had to accept state intervention in joint questions (e.g., establishment of parishes) and purely religious ones (eg, regulation of religious communities); in return, it could count on state support, which included money. The first diocese was established in Quebec in 1674.

Gradually a distinctive Christianity developed. It was homogeneous, because Protestants were allowed into the colony only for brief visits (see Hugenots). Most members of the population practised their faith, following the severe Catholicism developed primarily by Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier (see Jansenism). The parish was the backbone of religious life and was financially administered by church wardens (the only elected officials in New France), who were usually influenced by the parish priest. In 1760 Canada had about 100 parishes, most of them run by diocesan clergy (84 members), of whom four-fifths were Canadian-born. The priests were assisted by 30 Sulpicians, 25 Jesuits and 24 Récollets, and over 200 nuns belonging to 6 communities who were responsible for educational and welfare activities. These communities of men and women could offer their services free because the king had granted them lands and financial support. This equilibrium, which characterized church-state relations from 1660 to 1760, was vulnerable to the changes in the balance between the forces that composed it.

The Church Under British Rule

After the Conquest of 1759-60, the Catholic Church of Quebec, already weakened by the effects of war, had also to deal with new British and Protestant masters (see Protestantism). The new authorities were expected to favour the Church of England (see Anglicanism) and attempt to convert their new Catholic subjects. The free exercise of the Catholic rite was guaranteed in the terms of the surrender; although the practices were only tolerated by the British, gradual freedom for Roman Catholics soon evolved. Nevertheless, the British interfered in the nomination of bishops and sometimes priests, and required the clergy to communicate certain government documents to their parishioners. The Quebec Act of 1774 further guaranteed free exercise of Roman Catholicism and made it easier for Catholics to enter public office. To protect the newly won freedoms the bishops preached obedience (in varying degrees), led their people in opposition to the American invaders of 1775 and sang hymns of thanksgiving for British victories over the French in the American Revolution.

In other parts of present-day Canada, the French church had established missions in the Maritimes by the early 17th century and in Newfoundland by mid-century, but non-francophone Roman Catholics soon settled in these areas as well. Late in the 17th century Irish Catholics began to arrive in Newfoundland, which was under Quebec's jurisdiction until 1713; that year France ceded Newfoundland to Britain by the Treaty of Utrecht, and ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the island passed to the vicar apostolic of London. In 1796 Newfoundland became a separate diocese under Bishop J.L. O'Donel.

Growth of the Church

In the late 18th century many Scottish Roman Catholics settled on Prince Edward Island and in Nova Scotia. For various personal, political and ecclesiastical reasons, however, the church there and in the other settled parts of present-day Canada, excepting Newfoundland, remained under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Quebec until 1817; that year Nova Scotia was made a separate vicariate apostolic under Bishop Edmund Burke. Thereafter, new vicariates and dioceses appeared as settlement spread. The growth of the church in Anglophone Canada was spurred especially by the arrival in the 19th century of large numbers of Irish immigrants.

By the early 19th century, numerous Catholics in Lower Canada, especially the rising professional class, had distanced themselves from their church. Priests could not direct the populace as they had done before, and people began to neglect their religious practices. Church authorities thwarted efforts from secular denominations and won official recognition from the bishop to encourage education (including religious vocations), and revive the Catholic faith. But the 323 priests could not meet the needs of Quebec's 500,000 inhabitants and could no longer count on the support of male religious communities, which (apart from the Sulpicians) had disappeared, or of female ones, which were in difficulty. The Parti Patriote (founded 1826), which had mass support, proposed a liberal program that alarmed the clergy and began a Protestant-style proselytism, primarily around Montreal. The beleaguered bishop of Quebec won the nomination of a Montreal auxiliary, Monseigneur Jean-Jacques Lartigue, who became bishop of Montreal in 1836. Lartigue condemned the Rebellions of 1837-38 but, because of this support for the government, he temporarily alienated himself from his people.

The church was as badly shaken as the rest of society by the insurrection's aftereffects, but it was the first to recover. Under the dynamic new bishop of Montreal, Monseigneur Ignace Bourget (installed in 1840), the clergy assumed increasing power. Bourget set out to "Christianize" and "regenerate" society, applying the ideas of his predecessor and using the populist sermons of the French Monseigneur Charles de Forbin-Janson (see Evangelism) to advantage. Bourget made full use of the religious press that was run by skilled laymen; he headed fund drives in the city and made begging trips to Europe. He worked for the people, allying his church with Rome on liturgy, theological studies and devotions. He supported campaigns for public morality (e.g., Temperance campaigns and the fight against "evil" literature led by the Oeuvre des bons livres and the Cabinets de lecture paroissiaux), ran a social-assistance program for the poor, the sick, the orphaned and the handicapped, and preached social mutual assistance. The Montreal example was followed throughout Quebec, though often to a lesser degree.

During the same period a sharp increase in religious vocations led to more and better-served parishes; the number of dioceses (10 in 1900) rose with the birthrate. The priests, now more numerous, often involved themselves in secular activities and seemed to run everything in Quebec. Parishes periodically called in specialists (Jesuits, Oblates, Redemptorists, Dominicans and Franciscans) to preach at spiritual-renewal missions. The lay response seemed satisfactory: most people were now practising and an elite could even be called devoted.

Catholicism in both English and French Canada was aligned with international Catholicism, whose leadership was becoming progressively more defensive and fearful of post-revolutionary (American and French) Western society. During the early 19th century sectarian violence grew, as demonstrated by the brawling of Irish Catholics with Irish Protestants (see Orange Order) on several occasions in Upper Canada, and by the fighting involved in the so-called Shiner's War of the 1840s. Catholic churchmen saw the social upheaval resulting from industrialization and urbanization as the work of the devil, the French Revolution, Freemasonry, Socialism and laissez-faire capitalism, and they urged the faithful to return to a stable Christian social order such as that prevailing in the Middle Ages.

The Catholic Church and the Schools

19th Century

One social area in which the church was always active was education. Catholic clergy throughout Canada were pioneers in early 19th- century education, establishing small local schools with teachers whose primary concern was the moral education of their charges. But toward mid-century the state began to provide schooling, thus moving into an area of social concern that had been a church responsibility for centuries. The first school Act (1841) of the Province of Canada was aimed at establishing a Christian but nondenominational school system. However, political realities ensured that Canada East soon developed a dual confessional school system (Catholic and Protestant), whereas Canada West allowed the creation of a divided, state-supported school system, one section being nondenominational (public), the other confessional (Separate Schools). The latter soon became largely Roman Catholic. In subsequent decades other provinces modelled their school systems on either the Quebec or Ontario standards. As the state took over the schooling of Canadians, the confessional and Catholic schools obtained recognition in law.

During the second half of the 19th century, the Canadian Catholic hierarchy was determined to strengthen its Catholic schools, while public-school promoters argued that their "public" schools alone should enjoy the support of the state. There ensued lengthy and virulent controversies such as the New Brunswick School Question of 1871, the Manitoba Schools Question of the 1890s and the North-West Schools Question at the turn of the century; the Ontario Schools Question of 1912-27 was not only a fight between English Protestants and French Catholics, but also the result of a power struggle between French-Canadian and Irish-Canadian clerics within the church.

Other parts of Canada experienced similar quarrels as ethnic groups struggled for church control, but in the process some clerics learned to value diversity and to respect one another. Meanwhile, the church had founded numerous denominational institutions of higher learning. A number of Canadian universities originated in this way, including the University of Ottawa and the University of St. Michael's College (Toronto). In most cases, their administration has passed gradually into secular hands.

As the church increased its influence on society, especially in French Canada, some clergy were tempted by politics. Imbued with ultramontane principles (see Ultramontanism), and fearing reforms being suggested by the Liberal Party, the Québec clergy accused that party's supporters of Catholic liberalism and denounced them at election time. In 1871 laymen supported by Bourget and Monseigneur Louis-François Laflèche published an election manifesto, the Programme catholique, which could have led to religious control of the provincial Conservative Party. The strong reaction of 3 bishops (Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, Monseigneur Charles LaRocque and Monseigneur Jean Langevin) and of politicians doomed the project and made public the split between moderate and intransigent ultramontanists ("Programmists").

In 1875, the groups united in a virulent denunciation of Catholic liberalism; in 1876 the election results in 2 provincial ridings were annulled because of "undue influence" by the clergy. Tension grew between church and state. Rome was consulted, and it sent an apostolic delegate, Monseigneur George Conroy, to re-establish harmony between the prelates and force them to declare that their condemnation of Catholic liberalism had not been directed against the Liberal Party. Clerical intervention in politics was thereafter more discreet.

During the latter 19th century, Quebec Catholicism discovered a missionary vocation that persists today. Nuns, priests and brothers first established missions in the rest of English Canada (including the present-day Prairie provinces and Northwest Territories) and the US, and then throughout the world (see also Missions and Missionaries). Initially the Oblate missionaries from France, and Canadian clergy (mostly from Quebec), founded, and strongly supported, missions, infirmaries and schools throughout the Prairies, BC and the North. The church was active in broader social concerns as well. Various 19th- century sociologists had recognized that new forms of society, with new needs, were being created by growing industrialization and urbanization. Protestants responded to the new "social question" with the Social Gospel movement.

20th Century

By the 20th century, Quebec Catholicism was preoccupied with social concerns. Aware of the problems created by the new technology, migration to the cities, and challenged by Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, the clergy developed a social doctrine to guide the new society. In Quebec, the Jesuits were particularly active through the École sociale populaire. Their Programme de restauration sociale (founded 1933) was the main inspiration for the political movements Action libérale nationale, Bloc Populaire Canadien and, to a lesser degree, the Union Nationale. They supported and directed Catholic trade unions formed from 1907 to 1920, credit unions, co-operatives and every kind of league, each of which had Roman Catholicism as its main characteristic.

Moreover, the church in Quebec continued to control education. Secular activities left only about 45 per cent of the clergy for parish duties. This disequilibrium posed few problems, since the province's clergy kept growing: 2091 in 1890, 3263 in 1920, 5000 in 1940 (a ratio of 567, 578 and 539 parishioners to each priest), exclusive of religious communities. The faithful were guided by their priests and in their religious practice emphasized parish missions, pilgrimages and provincial, regional and local conferences. Catholic Action helped to form "new" Catholics, whose methods disturbed traditionalists and sometimes led to conflict with clergy.

In Canadian Catholicism's commitment to sociopolitical activity, doctrine and moral teaching were stringent, and political and social involvement was uncompromising. The Great Depression of the 1930s again tested the readiness of Catholics to deal with major social problems. The hard times that gave birth to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation also saw the beginnings of the Catholic Antigonish Movement. Many Catholic bishops condemned the CCF because of its socialist characteristics. True to its tradition the church was generally conservative, supporting the status quo and uneasy with change. The Second World War brought with it an increasing awareness of the outside world among Canadian Catholics, and made the church appear to many Catholics to be too self-sufficient and complacent.

From 1850 to 1950, Catholicism became highly centralized and disciplined; while regular worship had become habitual for most Canadian Catholics, it had done so in the form of an increasing number of devotions set in a framework of intense and colourful piety. Devotion to the papacy had intensified after 1850, culminating in 1870 when the dogma of papal infallibility was defined, and successive Popes strongly encouraged special devotions, e.g., to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Virgin Mary or Saint Joseph. The Catholic Church built upon centuries-old customs in nurturing various forms of piety, such as the Rosary, the scapular, adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, and the Forty Hours; pilgrimages became popular, both to shrines in Europe and the Holy Land and to various shrines in Canada. The crucifix adorned most Canadian Catholic homes, and wayside crosses and shrines were erected in massively Catholic areas. This intense piety would dissipate only after 1960.

Canadian Catholicism emerged from the Second World War as a triumphant church, as is suggested by the pageantry surrounding the 1947 Marian Congress in Ottawa and the installation ceremonies of Archbishop Paul-Émile Léger in Montreal in 1950. But the conservative administrations of Pope Pius XII and US President Eisenhower ended in the late 1950s, and the new liberal spirit emerging in the Western world began to affect the church in Anglophone Canada.

Catholicism and the Quiet Revolution in Quebec (Mid-20th Century)

In Quebec the changes were more extreme and jarring than they were elsewhere in Canada. The Second World War and the postwar periods were a time of profound transformation for all of Quebec. Traditional values, even religious ones, were challenged by people wanting an expansion of missionary and community values, an increased lay role in the church and a warmer welcome for the positive values of the modern world. Some groups, e.g., the Faculté des sciences sociales of Université Laval and the Commission sacerdotale d'études sociales, proposed modern solutions to social problems. They were in the forefront of opposition to the Duplessis government during the 1949 Asbestos Strike and inspired a collective pastoral letter of 1950 that expressed a new sensitivity to labour and to women. The Roman Catholic Church in Quebec backed the strikers. For the first time, it sided with labour in an industrial dispute. This put the bishop’s office in direct conflict with Duplessis.

In a sermon delivered at Notre-Dame Basilica, the archbishop of Montreal, Joseph Charbonneau, told parishioners: “The working class is the victim of a conspiracy aimed at crushing them, and when there is a conspiracy to crush the working class, it’s the Church’s duty to intervene. We value people more than capital.”

Until 1959, however, Catholicism in Quebec still wore the face of a conservative institution. Then the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s forced the church to face some weaknesses (see also Women and the Quiet Revolution). In just a few years, a wind of change produced both the declericalization of society (welfare, health and education passed from church to state control) and the secularization of institutions (e.g., Catholic trade unions shed their confessionality to become the Confederation of National Trade Unions), and associations, social clubs, universities and the state all adopted religious neutrality. At the same time, much of the population ceased attending worship services on Sunday, and there was a break with traditional morality, especially in sexual matters, a major exodus of members of the clergy and of religious orders, and a sharp drop in religious vocations. The hierarchy and the clergy as a whole seemed overwhelmed, and kept prudent silence.

The renewal of Catholicism after 1960 was also apparent in the church's new openness to other Christians and other religions. Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans and other Protestants cooperated in certain missionary activities, in social justice endeavours and in local and regional pastoral initiatives.

The Church and Vatican II

In 1959, Pope John XXIII announced the convening of an ecumenical council, and the Catholic faith throughout the world began to seek new forms of expression and witness. In Vatican Council II (1962-65) international Catholicism was caught up in a whirlwind of change and challenge that sought to revitalize all areas of Christian concern, from theology to political action, from spirituality to administration, from ecumenism to moral codes. A number of Canadians (e.g., Cardinal Léger, theologian Bernard Lonergan and humanitarian Jean Vanier) emerged as leaders of the aggiornamento (modernization movement) in various spheres of activity.

The church in Canada could no longer rely on social custom and constraint, as it had done in the past, to ensure church attendance or to influence government decision making. The effects were particularly marked in Quebec, where the Quiet Revolution coincided with the church's international renewal. The loosening of these ties to society led to a decade or more of generalized confusion for many Canadian Catholics. Those who had attended mass every Sunday fearing the pain of sin learned the importance of personal responsibility in attendance at worship. Those who saw the cleric as "another Christ" discovered that he was also human. Those who were concerned over sexual sin as "the only sin" discovered the importance of loving God and one's neighbour. Churchmen learned to share some authority and Catholics were called upon to take some responsibility.

One sign of Catholic renewal was a softening of the teaching on marriage. Before 1960, a Roman Catholic needed special permission to marry a non-Catholic, and the non-Catholic partner was required to agree, in writing, that the couple's children would be educated in the Catholic faith. After Vatican II, the church discovered the primacy of conscience and the real Christian faith of many non-Catholic Christians. This led to less stringent disciplinary dictums, many Catholic pastors now acknowledging that the children born of a mixed marriage are best raised in the church of the more committed Christian partner. The ecumenical campaign was strengthened in the process.

Indeed, Vatican II and the papal documents that followed in its wake constitute a milestone in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. New bridgeheads were established on the shores of a postmodern world whose links with the Christian church had been deteriorating since the 17th century. The fear of the world that characterized so much of previous spirituality became an open-hearted movement towards contemporary humanity. There was greater emphasis on the church as a people of God, and less on the dominant hierarchy; the laity made some advances (although in the early 1980s Canadian women were lobbying for access to the hierarchy through women's ordination); Protestants were promoted in the eyes of the Roman Catholic Church from the rank of heretics to that of "separated brethren"; the developing nations were given their due as an area of major concern to the church; the scarecrow of socialism became acceptable ideology under certain circumstances; and the treatment reserved for linguistic, cultural and political minorities was recognized as a valid test of the quality of governments.

Forms of worship changed as well after Vatican II, and many of the changes centered on the renewed emphasis on the people as the principal constituent of the church. Although communion remains the focal point of the mass, it is not linked as closely to individual confession as it formerly was. Priests now conduct mass facing the people, and the Latin of the Tridentine rite (the Latin Mass used until the introduction of the current Mass by Vatican Council II) has given way to vernacular languages. The practice of preaching and interpretation of scripture has been revived, and lay members of the congregation participate more fully in the various aspects of the worship service. There is also a resurgence of congregational singing and popular hymnology. At the same time, certain features of popular piety (e.g., benedictions, stations of the cross) have virtually disappeared (see also Charismatic Renewal).

In the wake of Vatican II the Canadian Catholic Church reassessed its attitude toward "other" linguistic and cultural groups. For instance, in early Ontario and English Canada the leadership of various Catholic churches had been largely French or French Canadian (there was no francophone bishop in the Maritimes before 1912). As an English-speaking (largely Irish) hierarchy came to the fore in these areas, ethnolinguistic polarization developed simultaneously in the ranks of the hierarchy and in Canada generally. The result was a Canadian Catholic Church that pretended to be united, but was in fact separated on English-French lines. While Rome preached bilingualism for the Canadian church, Canada's bishops indulged in their own brand of ethnocultural warfare.

The new spirit that prevailed after 1960 led Canada's Catholics to reassess their attitudes. At the centennial of Confederation (1967) as well as on several other occasions ranging from the adoption of Quebec's charter of the French language (1977) to Canada's constitutional debate (to 1982), the bishops of Canada, Quebec and Ontario issued a series of statements on the question of minority language rights and the status of French and English in Canada. For the first time in a century, the leaders of Canada's Catholic church were constructively coming to grips with an issue that had long divided them. The Canadian Catholic Church had practised bilingualism before Confederation, a policy that had served it well in evangelizing much of Canada, and it returned to this policy. Given the church's numbers and geographic distribution, the language policy contributed immensely to French-English understanding in Canada.

The turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s dramatically affected ecclesiastical institution: the network of parishioners and parishes remained virtually intact; the organization of religious communities of men and women rethought their objectives; confessional schools and some private colleges expanded; a new plan for parish action and greater lay participation in religious activities thrived. The episcopacy more frequently joined in Ecumenical Social Action, and took positions on such topics as birth control and abortion (1977, 1981) and the economic crisis (1982). But it is perhaps at the level of popular religion that the continuity and the hopes are most visible, given (among other things) a new interest in scripture, the continued popularity of pilgrimage and the growth of charismatic religion, the multiplication of small groups interested in spirituality, and the emergence of Catholic interests. For more than 100 years Protestants had outnumbered Catholics in Canada; however, by 1971, for the first time since Confederation, Catholics outnumbered Protestants.

The rapidly changing Canadian church experienced a climactic event in September 1984 when Pope John Paul II visited Canada. This pontiff, who was seen by more people than all other popes combined, was the first reigning pope to set foot in Canada. He visited many regions, preaching a gospel of peace, reconciliation and disciplined belief. To fulfill a promise made to the residents of Fort Simpson, NWT, where he was unable to land because of fog, he returned in September 1987.

Indigenous Children and Residential Schools

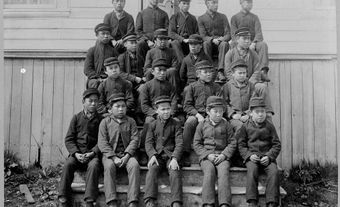

During the 1990s, Indigenous peoples were calling for self-government, better living conditions and more equitable treatment from the government of Canada, as well as public apologies and financial compensation from the institutions that had abused them in the past. A primary target of their grievances was residential schools, institutions that had been funded by the government of Canada and directed by Canada's leading Christian churches.

An estimated one-third of Canada's Indigenous children spent some time in a residential school from the 1880s to the 1960s, a time when these schools were practically the only avenue available to Indigenous children seeking an education. Two-thirds of the residential schools were administered by the Catholic Church and entrusted to the Oblate Fathers. Many residents experienced physical, emotional and/or sexual abuse of at the hands of school staff. (See Chanie Wenjack; Truth and Reconciliation Commission; Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.)

Dropping Membership

In the 1990s, a renewed Canadian Catholic Church faced challenges. A drop in church attendance, the widespread questioning of Catholic moral teachings, the dearth of new vocations to the priesthood and the religious life, and the waning of church influence in public life have caused many faithful to give serious thought to their faith. The simultaneous chaotic growth of new religious movements, new age thinking, secular values and new fundamentalisms, movements that frequently challenge or deny the ordered world of traditional Catholicism, contribute to changes in attitudes. Yet, some remember that the triumphant Catholic religious world that they grew up in was a temporary phase in Christian history. (See Evangelical and Fundamentalist Movements.)

In 2004, the Catholic Conference of Bishops reported 80 active and 59 retired cardinals, archbishops and bishops in 5,681 parishes and missions in Canada.

Eastern Rite Catholic Churches

A small but important segment of Canada's Christian population belongs to the Eastern Catholic or Eastern Rite churches, which trace their theological, canonical and spiritual traditions to the early Christian culture of the Eastern Mediterranean world. As distinctive ecclesial entities, the Eastern Catholic churches emerged only after Christian unity had succumbed to a centuries-long process of estrangement, culminating in the defeat of the Greek city, Constantinople, by Western crusaders in 1204 and the establishment of a Latin patriarchate, with the tacit support of Pope Innocent III. With the exception of the Maronite Catholic Church and the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, which claim always to have been in communion with the bishop of Rome, all Eastern Catholic churches originated from Western missionary efforts to return Eastern Christians to the immediate jurisdiction of the papacy, or, in the case of the Bulgarian Byzantine Catholic Church, from a spontaneous desire for union with Rome.

Throughout their history, Eastern Catholics have struggled to maintain their own traditions against the Latinization or absorption into the Latin (i.e., Western or Roman) Church and have sometimes experienced hostility from their parent Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox churches. The negative effects of Latinization are most evident in the collapse of traditional Eastern forms of monastic life, which have been supplanted by Western-style religious orders, and in the liturgy. For Eastern Christians in Canada (and the US), the prohibition of married parish clergy, dating from the 19th century, is perhaps the most painful reminder of Latinization.

Although in union with Rome, each Eastern Catholic church remains distinct, particularly in liturgical practices and devotional life. Eastern Catholics celebrate their faith in one of five different rites: the Alexandrian, Antiochene, Chaldean, Armenian and Byzantine rites. Historical circumstances, especially the persecution and suppression of Eastern Christians in the Ottoman and Russian empires and in the former Soviet Union, forged an unbreakable bond between religion and ethnicity that helped Eastern Christians to survive but now hinders future growth outside their traditional homelands. In keeping with the theological understanding of the church current at the time of their establishment, Eastern Catholic churches frequently were reduced to the status of a mere rite in the larger Roman Catholic Church. The Second Vatican Council and subsequent papal pronouncements have corrected this, so that today Eastern Catholic churches are treated as sister churches of the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1990, the Code of Canons of the Eastern churches was promulgated by Pope John Paul II. According to this document, Eastern Catholic churches may be grouped into 4 types:

- patriarchal;

- major archiepiscopal;

- metropolitan; and

- other churches.

A patriarch is elected during the periodic meetings of the synod of bishops of a particular church. After his election and enthronement, he requests communion from the Pope. A major archbishop is elected in the same manner as a patriarch, but before he is enthroned, his election must be confirmed by the Pope. The Pope names metropolitans (a bishop with authority over other bishops) after consulting a list of candidates presented by the bishops of a particular church.

The Maronite Catholic Church traces its origins to disciples of the fourth-century monk Saint Maron in Lebanon. By the eighth century this largely monastic-centered community elected a bishop as their head. During the twelfth century the Maronites came in contact with Latin Christianity thanks to the Crusaders, and in 1182 they formally confirmed their relations with Rome. Lebanon remains the home for most Maronite Catholics. In Canada, the bishop of the Eparchy of Saint-Maron of Montreal leads some 80,000 adherents in 14 parishes. The Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, dating from the 15th century, comprises 2 dioceses in southern Italy and the monastery of Santa Maria di Grottaferrata south of Rome.

In the wake of the Council of Florence in 1439, groups of Armenian, Coptic and Syrian Christians entered into short-lived unions with the Roman Catholic Church. These churches were revived in the 18th century: the Armenian Catholic Church in 1742, the Coptic Catholic Church in 1741, and the Syrian Catholic Church in 1782. A small apostolic exarchate of Armenian Catholics exists in Canada, and there are 8 Coptic Catholic parishes throughout the country. Syrian Catholics, centered in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, currently have no official presence in Canada. Other Eastern Catholic churches include the Chaldeans (1553), the Syro-Malabars (1599), the Ethiopians (1626), the Melkites (1744), the Ukrainians (1595-1596), the Ruthenians or Rusyns (1646), the Romanians (1700), Byzantine Catholics of Krizevci in the former Yugoslavia (1777), the Bulgarians (1861), the Syro-Malankarans (1930), the Hungarians (1912), the Greeks (1911) and the Slovaks (1968).

The Greek-Melkite Catholic Christians are organized under the bishop of the Eparchy of Saint-Sauveur of Montreal (created in 1984) and number approximately 43,000 adherents across Canada. Slovak Catholics received their own diocese in 1980, when Pope John Paul II created the Eparchy of Saints Cyril and Methodius of Toronto, originally under the care of Bishop Michael Rusnak.

The Ukrainian Catholic Church is the largest Eastern Rite Catholic church in Canada. Brought by Ukrainian immigrants at the end of the 19th century, the church received its first bishop in 1912 when Pope Pius X appointed Nicetas Budka to the episcopate. The head of the Synod of Ukrainian Catholic Bishops is located in Winnipeg and he oversees the Canadian metropolitan province, consisting of 5 dioceses (eparchies): the metropolitan see of Winnipeg, and the eparchies of Edmonton, Toronto, Saskatoon and New Westminster. Religious orders contribute significantly to the spiritual life of Ukrainian Catholics, and include the Order of Saint Basil the Great or Basilian Fathers, Redemptorist Fathers, Studites, Basilian Sisters, Missionary Sisters of Christian Charity, Sisters Servants of Mary Immaculate, and Sisters of St. Joseph.

Theological education of clergy and laity is assured by the church's own Holy Spirit Seminary in Ottawa. The Metropolitan Andrey Sheptyts-ky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies was established in 1992 as part of the Faculty of Theology of Saint Paul University in Ottawa and offers specialized studies in Eastern church history and theology. A scholarly journal, Logos, gives Ukrainian and other Eastern Catholics a strong voice in the academic world.

Holy Days

Since the early centuries of Christianity, Easter, which commemorates Christ's resurrection, has been the central feast of the liturgical calendar. Easter Sunday occurs following the first full moon after the vernal equinox. The holy week begins with Palm Sunday, one week before Easter Sunday, and is the anniversary of Jesus Christ's entry into Jerusalem. On the Thursday before Easter Sunday, Catholics commemorate the Last Supper followed by Good Friday, the day of the crucifixion. Over time, other seasonal and thematic feasts have been added; in contemporary Catholicism, Christmas (feast of the birth of Jesus) and Epiphany (feast of the early manifestations of Christ's divinity) have been highlighted along with Easter as the central feasts of the year. The Feast of the Epiphany is celebrated on the first Sunday after Christmas (see Religious Festivals).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom