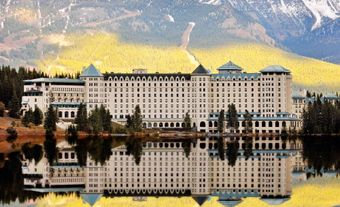

Fairmont Banff Springs (formerly Banff Springs Hotel) is a luxury hotel located in Banff National Park. (See also National Parks in Canada; Alberta.) This famous Canadian building is an excellent example of a resort hotel. It is known for its architectural design within a natural setting (the Rocky Mountains) as well as its ability to support a thriving sports and leisure culture. The hotel was developed as part of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s network of hotels, which were constructed across Canada in order to encourage the use of its transcontinental lines. Known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” the architecture of the Fairmont Banff Springs is predominantly in the Scottish Baronial style, featuring an Arts-and-Crafts interior.

The Bow Valley

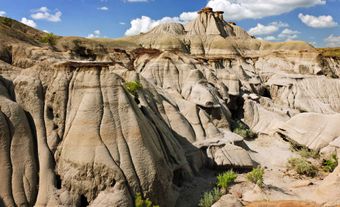

The setting of the hotel is a confluence of rivers, forests, mountains and a natural mineral hot spring. The hotel is located near the foot of Sulphur Mountain and provides views of the Bow River, Fairholme Range, Tunnel Mountain and Mount Rundle. The nearby Banff Upper Hot Springs, which were promoted as therapeutic waters, were a strong motive for locating the hotel at the highest point above the crossing of the Bow and Spray Rivers.

History and Development

Historically, the Fairmont Banff Springs was closely tied to the passing of the Canadian Railway Bill of 1881 under Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald. It was during this time that the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) completed its transcontinental route in British Columbia (1885). Thereafter, the CPR embarked on the development of accommodations for those that traveled on their lines.

The tourist profile of the 1880’s included the affluent who went on travel tours to spa resorts. Cornelius Van Horne, a prominent business-man and CPR’s president, wanted to provide a luxurious hotel experience for these guests exploring the west. Van Horne was an advocate for the protection of the Banff Hot Springs, seeing it as an opportunity for the development of an exquisite natural resource to supplement the hotel.

19th Century

The first iteration of the hotel was completed in 1888 by American architect Bruce Price. Price built a five-story, wood-frame structure at an unprecedented scale, which connected the thermal mineral spring water through a pipe system into its many pools. The idea that architecture should be an organic element of its surroundings, typical of architectural thought of the time, was incorporated by Price’s design, with a focus on creating luxury. The design indulged in the French chateau style as well as the late Victorian, typical of Canadian architecture at the time. The hotel could accommodate around 280 guests and featured steep hip roofs, dormers, turrets, bay windows and a cedar shingle roof. The high peaks fit perfectly into the sea of pine and spruce trees.

20th Century

The hotel’s early days featured Swiss mountaineer guides (1899) provided as a service to the guests. These guided adventures in the mountains or through the rivers were evidence of the evolving culture of the time. Increasing demand for accommodation led to the period between 1900 and 1910, which included both modifications and additions, with half a million dollars put into a five-story extension to the south of the building by Montreal architects Hutchinson, Wood and Miller. In 1910 maximum capacity was quickly reached once more and additions were beginning to form an aesthetic that did not serve the majestic vision set forth by the leadership. With that in mind, the CPR involved another American Architect, W.S. Painter, to provide a more cohesive concept. He built an 11-storey central tower, which was completed in 1914 and cost two million dollars. The hotel accommodated up to 300 guests. It was built using a progressive style of steel and concrete construction. Painter followed Price’s concept of the French chateau style, but included predominantly Scottish baronial influences. Price’s cedar-shingles and turrets were replaced with flat dormers and circular arched windows with a limestone facade, changing its aesthetic substantially. Bay windows and balconies allowed the architecture to provide extended views of the mountains and landscape. The new hotel tower featured a bathing area with a variety of offerings including cold fresh water, hot mineral water, Turkish and Russian baths, and private sulphur baths. To further develop the image of the hotel, Kate Reed, wife of the CPR Director of Hotels, served as the interior decorator.

The hotel experienced great periods of growth in the 1920s and 1930s. Among the events the hotel administered to captivate their guests, included a summer festival featuring the dance and song of local Stoney-Nakoda Indigenous people as well as a music festival that gave visitors a strong sense of the culture of the area. Amenities have varied over time and have been dependent upon cultural changes in the area. These activities have included horseback-riding, canoeing, water rafting, tennis and golfing (an 18-hole golf course was built in 1927).

Fire

A devastating fire in 1926 burned the north wing of the hotel to the ground. From 1927 to 1928, a $9 million dollar budget was reserved to complete W.S. Painter’s plans. J.W. Orrock updated the plans, enlarged them and adjusted the roofline. Construction commenced for a new north wing and south wing made out of steel and concrete, placed at angles to the central tower, and faced with Rundle stone. The hotel rooms were done in a variety of styles, along with the opulent interiors of the halls of the hotel, which displayed oak paneling on its walls, stained glass, a marble fountain, extensive use of Tyndall stone, Tiffany sconces, coffered ceilings, and lime flagstone on the floor.

The years between 1942 and 1945, closed the hotels doors due to the Second World War. The post-war clientele changed to include the middle class who now had access to travel opportunities only available to the elite in the past. Furthermore, in the development of the hotel’s history, it was not until 1969 that the hotel opened its doors to four-season tourism.

Restoration and Renovation

In 1987, with the coming of the 1988 Winter Olympic Games, $100 million was invested in restoring and renovating the hotel. In 1997, the hotel added a further $8 million of restoration work. The clientele of the 1990’s sought conference centre space, and it was during this time that Calgary architect’s Carruthers, Marshall and Associates took on the task of satisfying this need with a $25 million dollar renovation. Finally, in 1995, Calgary architect Robert LeBlond completed the luxurious new spa for the hotel with a budget of $12 million.

Architectural Overview

Overall, the Fairmont Banff Springs exhibits many European influences, which can be seen in the decor, furnishings and interior details, but Canadian images of local Indigenous culture and regional flowers complete its identity. The Arts-and-Crafts traditions are evident, showing off French, Scottish and Spanish traditions in the various rooms. Canadian as well as European manufacturers were involved in providing the interior details, including Montreal’s Castle and Son for the wood furniture, and Czech crystal chandelier and glass window manufacturers.

Heritage

Following the CPR’s restructuring in 2001, the Fairmont Banff Springs is operated under Fairmont Hotels & Resorts. The Fairmont Banff Springs shares a lineage with the Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise in Banff National Park, the Fairmont Le Château Frontenac in Quebec City and the Fairmont Empress Hotel in Victoria, British Columbia.

The hotel was declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1988. The hotel was also the subject of a commemorative stamp issued by Canada Post in 1993.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom