Amelia Yeomans (née LeSueur), physician, social and political reformer, temperance advocate, suffragist and public speaker (born 29 March 1842 in Québec City, Canada East; died 22 April 1913 in Calgary, AB). Yeomans practised in the burgeoning field of social medicine, where social and economic conditions are understood to impact health. She was unafraid to publicize her work and findings, shining a light into the darker corners of life, where social stigma and shame prevented people from venturing. Yeomans was an early leader in the women’s suffrage movement in Manitoba. Realizing that their goals were linked, Yeomans supported suffragists and helped ally the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union with their cause.

Early Life and Education

Amelia LeSueur was born into an affluent family in Québec City, where her father, Peter LeSueur, worked in the Civil Service Commission. Amelia was educated at home, and at the Provincial School along with her brother, since their parents placed great emphasis on education. Her brother, William Dawson, would later become well known as a civil servant, essayist and president of the Royal Society of Canada.

In 1860, when she was 18, Amelia married Dr. Augustus A. Yeomans, an assistant surgeon in the United States Army originally from Madoc, Upper Canada. The couple had two daughters, Lillian and Charlotte.

When Augustus passed away in 1878, Lillian decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and pursue a career in medicine. Since Canadian universities did not admit female medical students at the time, she enrolled in the University of Michigan’s School of Medicine in Ann Arbor. Amelia accompanied her daughter the following year, as a medical student herself. They faced a great deal of hostility as women in a primarily male domain and had to endure harassment from their fellow students, who saw Lillian and Amelia as interlopers.

Medical Career and Early Activism

After completing her studies in 1883, Amelia Yeomans settled in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where her daughter Lillian had moved after she graduated in 1882. Though Amelia began to practise medicine that same year, she did not get her licence to practise in Canada for another two years. For reasons unknown, she did not write examinations set by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba until February 1885.

Winnipeg experienced tremendous growth in the 1880s, as Ontarians and recent immigrants to Canada moved westward and into the city. Poverty, overcrowding, crime, poor housing conditions and a lack of medical facilities were problems in Winnipeg, where Yeomans carried out her work. She mainly treated patients who were unable to get adequate medical attention, practising in the burgeoning field of social medicine. The city’s problems were particularly pronounced in its North End district, where people living in close quarters had little access to sanitation, good jobs or the chance of a hopeful future. Winnipeg’s poor sewage system contributed to the general decline in public health.

Amelia and Lillian focused their attention on women and children’s diseases. About this time, Amelia began to take an interest in the health of prisoners and sex workers. Facing poverty and unemployment, some women took to sex work to support themselves and their families. Brothels flourished near the train station, catering to the many men who were moving from rural areas to the city. This development put further strain on public health, as the increase in sex work was accompanied by an increase in venereal disease.

The conditions in local prisons, where sex workers as well as homeless and abused women were often sent, were pitiful and shocking. With male and female prisoners sharing wards, towels and bedding, the spread of disease was swift. In response, Yeomans brought along her journalist friend E. Cora Hind as she made her rounds of the prisons. After gathering information from her visits, Hind wrote a series of condemning articles that caused a great furor in Winnipeg society, where to speak of such “indelicate” matters was considered unladylike. Hind wrote:

The cells are totally devoid of light or ventilation, except such as may be had through the doors. [...] No sleeping accommodation is provided, and no bedding is allowed, except that blankets are sometimes given to the women. [...] The wards are infested with vermin, drugs, lice, and cockroaches. [...] Some of the most abandoned are afflicted with syphilis and other loathsome diseases, and healthy prisoners are exposed to the danger of becoming similarly affected. The men and women are obliged to use the same towels, closets, etc., so that those who are healthy can scarcely escape the consequences.

Yeomans herself gave a public lecture to men in the city, in which she blamed men themselves for the problems of sex work and venereal disease amongst young women: “young women [are] made to suffer through the wickedness of men, their young lives ruined, while their betrayers moved untarnished in the ranks of society.” This was a bold step in a city where few had the courage to speak openly about such matters. Yeomans was unafraid to shine a light into the darker corners of life, where social stigma and shame prevented people from venturing.

About this time, the Winnipeg branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) started a campaign to help female prisoners. As part of this campaign, the WCTU sponsored a pamphlet written by Yeomans and addressed to women, outlining the dangers of “social diseases.” The public could no longer ignore the issue. Yeomans’ interest in women and children would continue — she helped found the Winnipeg Humane Society, which worked for neglected children in 1894, and instituted reforms for sex workers in Winnipeg.

Temperance Movement

Amelia Yeomans’ interest in the temperance movement took root when she realized how alcoholism was ruining the lives of many families. Advocating for prohibition, she joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which counted Nellie McClung and E. Cora Hind among its members. A national movement, the WCTU believed that the abuse of alcohol was the cause of unemployment, disease, prostitution, poverty and immorality. It therefore campaigned for the legal prohibition of all alcoholic beverages.

Yeomans attended and led several WCTU rallies in Winnipeg, where she urged citizens to confront the dangers alcohol posed to families. Her views on temperance, and allied issues such as women’s suffrage, made her a much sought-after speaker. She became president of the Manitoba WCTU in 1896–97 and, later, vice-president of the national WCTU.

Women’s Suffrage

After Manitoba’s entry to Confederation in 1870, the province’s law stated that, “No woman shall be qualified to vote at any Election for any Electoral Division whatever.” Over the next two decades, certain voting rights were extended to property-owning women, including the right to vote in municipal elections (1887) and in school board elections (1890). However, women still had very limited voting rights (see Right to Vote; Women’s Suffrage).

Amelia Yeomans was a staunch supporter of women’s suffrage, as were many temperance advocates. Like many of her peers, Yeomans argued for the vote as a way to preserve morality, arguing that “women were the most adamant protectors of community morals, purity and righteousness and would use their votes accordingly. Participation in the political process would enhance the authoritative influence over their children and inspire greater respect in husbands, sons and daughters.”

The women’s suffrage movement in Manitoba gained steam when a group of Icelandic women organized a suffrage league in the early 1890s. Icelandic women and their families had immigrated in large numbers to Manitoba in the 1880s. In Iceland, women could vote in church elections, and since 1882, widows and single women could vote at the municipal level. They could not accept disenfranchisement in their new home. Realizing that their goals were linked, Yeomans supported the league’s activities and helped ally the WCTU with their cause.

Yeomans’ belief in the political process pushed her to recruit women and men to the suffrage movement. Many women at the time were apathetic towards equal rights, especially those who came from privileged backgrounds and had fixed notions about women’s roles.

Mock Parliament

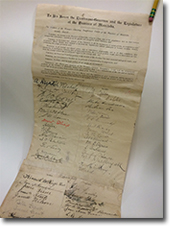

Amelia Yeomans was unrelenting in her work to extend the vote. The WCTU passed pro-suffrage resolutions, gathered support and engaged in public debates. In 1893, Yeomans and the WCTU presented a petition to the provincial government calling for votes for women. When this was ignored, Arminda Myrtal Blakely organized what would be the first mock parliament in Canada, which the WCTU sponsored. (The mock parliament was a powerful medium in which suffragists made their arguments for the right to vote. They were also organized to raise funds and public support for suffrage organizations.)

Staged at the Bijou Theatre on 9 February 1893, the mock parliament included Yeomans in the role of premier, speaking such lines as: “[A woman is] a rational, independent organism endowed by the Creator with certain natural rights which no one may in-fringe without wrong-doing.” E. Cora Hind and other temperance advocates also played members of the legislative assembly.

Yeomans had presented a petition to the legislature two days ahead of the mock parliament, asking “for an adjournment [...] on Thursday Evening, to attend the Women's Mock Parliament.” Though that petition failed, the performance went ahead. The Manitoba Free Press reported that at least 20 members of the Manitoba legislative assembly were in the audience, and that “wiser and better men left the hall than entered it during the early part of the evening.” It was followed by two suffrage petitions, each with thousands of signatures, shortly thereafter.

In November 1894, Yeomans and Hind announced the formation of the Equal Franchise Association (also known as the Equal Suffrage Club) at the end of a WCTU meeting. Yeomans was the association’s first president.

Later Life

Amelia Yeomans gained accolades in her later years as an accomplished and motivational speaker. The Calgary Daily Herald, for example, called her “a most eloquent and effective speaker.” She moved to Calgary in 1905, where she lived with her two daughters. Yeomans served as vice president of the national WCTU and honorary vice president of the Ottawa Equal Suffrage Society. According to the Archives of Manitoba, Yeomans was a founding member of the Political Equality League established in Winnipeg in 1912, though she lived in Calgary at the time.

Yeomans died on 22 April 1913 in Calgary, three years before women in Manitoba were extended the franchise.

Significance

Amelia Yeomans was a crusader who worked tirelessly to improve the conditions of the less privileged. Her temperance work stemmed from a deep certainty that alcohol was the root cause of poverty and a disturbing presence in society. That she spoke out against the horrors of venereal disease and fought to make sex workers visible in the public discourse in an atmosphere of Victorian prudery, shows her commitment to political and social reform. Although she did not live to see women get the vote, she played an important role in the women’s suffrage movement.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom