Childhood and Education

Alphonse-Télesphore Lépine grew up in a working-class family in the Saint-Jean district of Quebec City. His mother was named Éléonore Lessard, and his father, Charles, worked as a mason. As a child, Lépine received his elementary school training from the Brothers of the Christian Schools, who ran the local school. As a young man, he began work at the newspaper L’Évènement, where he was hired as an apprentice typographer. Once Lépine became qualified as a journeyman, he moved to the Quotidien de Lévis. Lépine joined the paper’s management as sub-editor and spent seven years learning about the publishing profession. At the same time, he was a frequent visitor to the Institut canadien in Lévis. It was there that he developed his public speaking skills. Lépine married Alexandrine Scott in 1883, and they moved to Montreal in 1885.

Activism and Involvement in the Union Movement

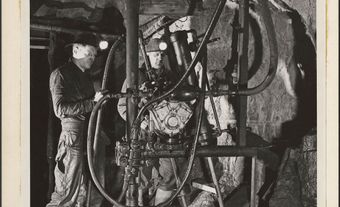

There are no traces of union involvement by Lépine prior to his arrival in Montreal. When he joined the union movement, it was in the process of institutionalization. In the fall of 1884, the Knights of Labor founded the Ville-Marie local assembly. Around the same time, the first working-class newspapers started to appear in Montreal. It was in this context that Lépine established the Trait d’Union printing company and joined the Union typographique Jacques-Cartier, the main union for francophone printers. Lépine became president of the Union in 1886 but gave up the position a year later. During his term, Lépine negotiated contracts with the City of Montreal and ensured that the Union typographique testified at the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada (1886–1889).

It is impossible to say with certainty when Lépine joined the Order of the Knights of Labor. It is known that he participated in the founding of the Montreal Trades and Labour Council (MTLC) in the spring of 1886 and became its secretary. He also worked alongside the Knights in the 1886 provincial political campaign in support of pro-worker candidates.

In 1887, Lépine’s activism took a new turn. He founded a worker’s newspaper, Le Trait d’Union, whose “formal intention [was] to facilitate the accord between Capital and Labor, an accord that [was] absolutely necessary to the prosperity of these two elements of public and private fortune.” He also published a pamphlet on the program put forward by the Knights of Labor, entitled Explication de la déclaration de principes des Chevaliers du travail. In the publication, Lépine discussed topics such as the cooperative economy and settling strikes by means of arbitration. In keeping with the Knights’ philosophy, Lépine wanted to overcome the antagonism among the different classes and sought balance and compromise between the interests of management and workers.

Political Involvement

A by-election was held in Montreal East in September 1888, following the death of the Independent Conservative Member of Parliament Charles-Joseph Coursol. This francophone-majority riding contained many working-class families and small merchants. The Conservative Party, conscious of the shift in Quebec voting trends from their party to the Liberal Party following the execution of Louis Riel in 1885, were ready to throw their support behind an independent candidate. Lépine, recognized for his talents at public speaking, attracted their attention, all the more so because he was at the centre of a network of well-established activists. He also enjoyed a privileged position as a printer, journalist and officer of the MTLC.

In 1888, both the MTLC and the sectoral trade unions supported the idea of an independent worker candidate. The liberal and conservative factions in the Knights of Labour put aside their differences; this benefited Lépine, who won the nomination in Montreal East, beating out the Liberal A.E. Poirier. While the main theme of the campaign was protectionism, Lépine was a proponent of the National Policy of the Conservative Party. He won the riding with a majority of slightly more than 800 votes and became an independent member of parliament in the House of Commons.

Lépine’s team was composed of many worker activists, chief among them members of the Union typographique Jacques-Cartier such as Albert Pigeon and Urbain Lafontaine. Over time, its activist base diversified to include shopkeepers and small merchants. Just prior to the 1891 campaign, Lépine’s candidacy was threatened from within the MTLC. A conflict between him and Joseph Béland, the working-class member of the Legislative Assembly for the riding of Montreal–Sainte-Marie, divided the MTLC into liberal and conservative factions. Nonetheless, Lépine won the nomination and was re-elected.

First Working-Class Independent Member Elected to the House of Commons

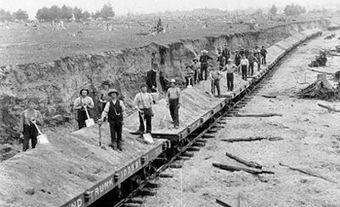

During his political career, Lépine sat on various parliamentary committees. Appointed in 1889 to the Standing Committee on Railways, Canals and Telegraph Lines, as well as the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonization, he was reappointed at each subsequent session until his defeat in 1896.

These two subjects were of prime importance for the Knights of Labor. The minister of agriculture was responsible for producing labour statistics. As for public services (telegraphy, transportation services, etc.), the Knights believed that these should be nationalized. In the face of the government’s failure to do so, Alphonse-Télesphore Lépine tabled a bill in February 1893 to institute an eight-hour working day for government employees and labourers. Although workers’ associations appeared satisfied by this initiative, the bill did not make it past first reading and died on the order paper. That same year, Lépine joined the Standing Joint Committee on Printing, which was responsible for publishing the House of Commons’ debates.

In the House of Commons, Lépine focused his interventions on subjects important to the Knights of Labor: creating an office of labor statistics, placing controls on immigration and supporting the temperance movement. As an independent member of parliament, he was given few chances to speak in the House of Commons and had to use other strategies to advance his files. Additionally, Lépine aligned himself with the Conservative Party without formally joining it. He also benefited from the patronage of conservatives who bought advertisements in the pages of Trait d’Union for close to $750 between 1887 and 1891. For his part, Lépine hoped to profit from these special ties so that influential Knights of Labor would be appointed to various positions in government bodies.

Lépine’s political adversaries pointed out his absences from the House of Commons and his support of the Conservatives, which are borne out in the statistics. A tally of recorded votes indicated that Lépine voted with the party in power 79 per cent of the time.

As a member of parliament, Lépine was also sometimes at loggerheads with his activist supporters. They were disappointed with the meagre tangible results that Lépine had managed to achieve. Lépine was abandoned by the assembly of the Ville-Marie Knights of Labor in 1895, and the MTLC withdrew their support for him in 1896.

Twilight of Lépine’s Career

Lacking the support of the workers’ associations, Lépine made the leap to the Conservatives in 1896. He came second in the new riding of Sainte-Marie against the Liberal Hercule Dupré. Subsequently, Lépine returned to private life and the printing business. Publicly, he rarely broke his silence on issues affecting the working class, and available sources suggest that Lépine ceased all political involvement. Lépine died in 1943 at the age of 88 years and was buried in the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery in Montreal. Fading from memory, his career became the subject of study only in the early 1970s, with the upswell of interest in social history and the history of the working class. Today, a park in the Plateau-Mont-Royal district of Montreal bears his name.

Publication

Explication de la déclaration de principes de l’Ordre des Chevaliers du travail pour l’instruction des membres de la société (1887).

See also Working Class History – Quebec.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom