The following article is part of an exhibit. Past exhibits are not updated.

The unification of Upper and Lower Canada was a recommendation of the 1839 report filed by Lord Durham, governor general of British North America, and the result of an imperial mission to investigate the rebellions of 1837–38, which took place in both colonies. Known as “Radical Jack,” Durham’s proposal was both politically progressive and very much of its time. The Durham Report, as it came to be known, also called for the creation of a responsible government dominated by anglophones — an attempt to assimilate Lower Canada’s francophone population.

Though Britain agreed to union and not responsible government — a chief concern of those who had rebelled — democratic reform grew over the ensuing decade as the result of a political partnership forged between leaders in anglophone Canada West (Ontario) and francophone Canada East (Québec).

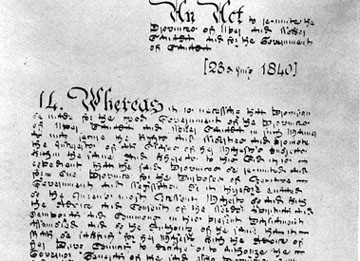

This exhibit commemorates the 175th anniversary of the Act of Union, which contributed to the arrival of responsible government in British North America.

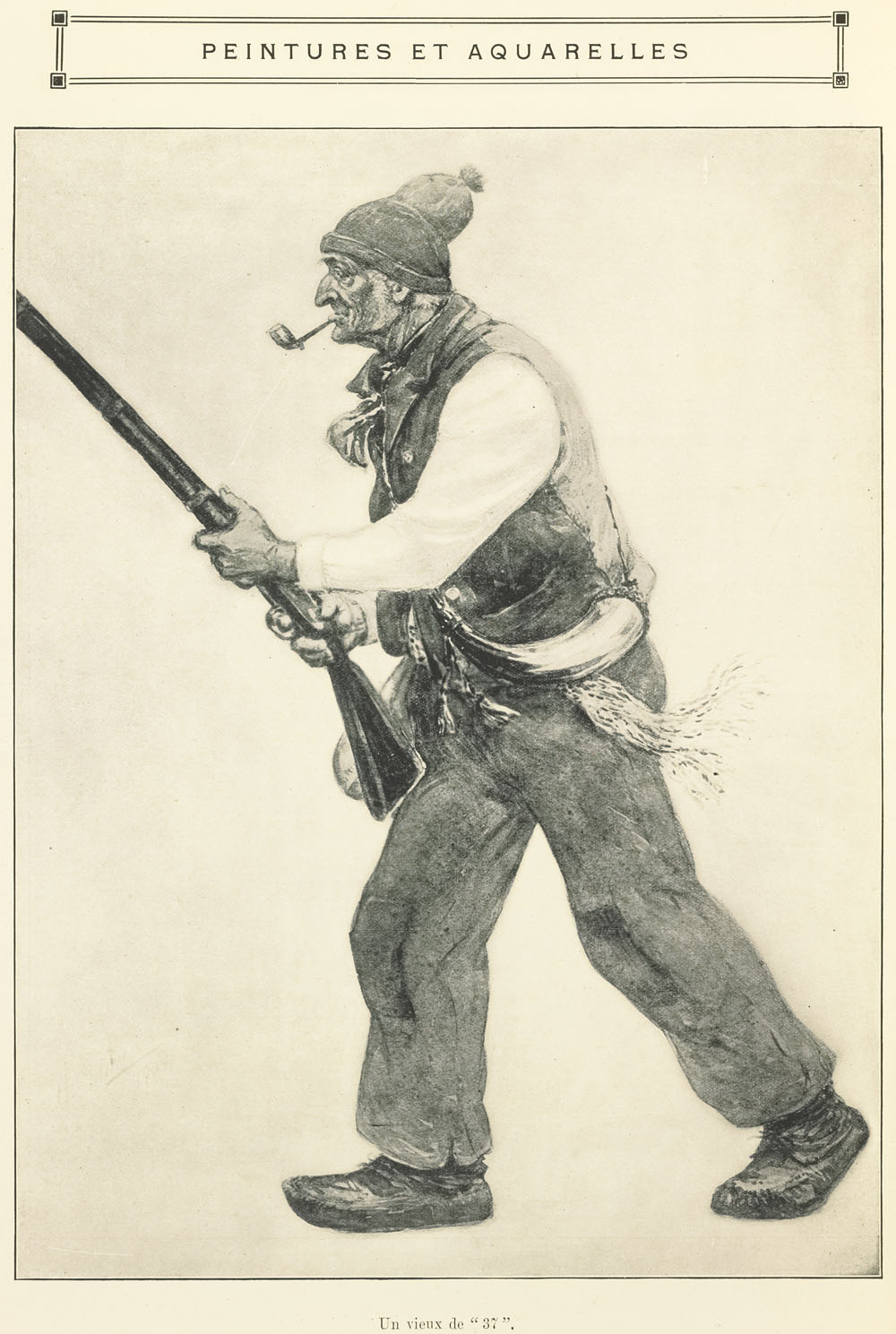

Rebellions of 1837–38

“Two nations warring in the bosom of a single state” — Lord Durham, 1838

Rebellions of 1837–38

In the 1830s, many reformers in Upper and Lower Canada demanded change to their system of governance, which concentrated power among small groups of ruling elites. Reformers in both colonies asked that the executive branch of government (an unelected Cabinet) be made accountable, that is responsible, to the elected legislature. When such calls for change were ignored, reformers grew militant and eventually took up arms.

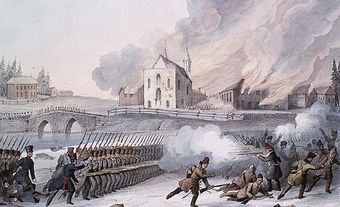

Rebellion in Lower Canada

French Canadian militants in Lower Canada took up arms against the British Crown in a pair of insurrections in 1837 and 1838. The twin rebellions, which killed more than 300 people, followed years of tensions between the colony's anglophone minority ( see also Château Clique) and the growing, nationalistic aspirations of its francophone majority. The rebels failed in their campaign against British rule, but their revolt fueled the speed of political reform and gave French Canadians one of their first nationalist heroes, Louis-Joseph Papineau.

Rumours and Reports

"The news are, I grieve to say, very bad from Canada; that is to say rumours and reports by the Papers, though we have no Official Reports. But [Prime Minister] Lord Melbourne hopes it may not be so bad as it is rumoured. There certainly is open Rebellion." — Queen Victoria, 22 December 1837

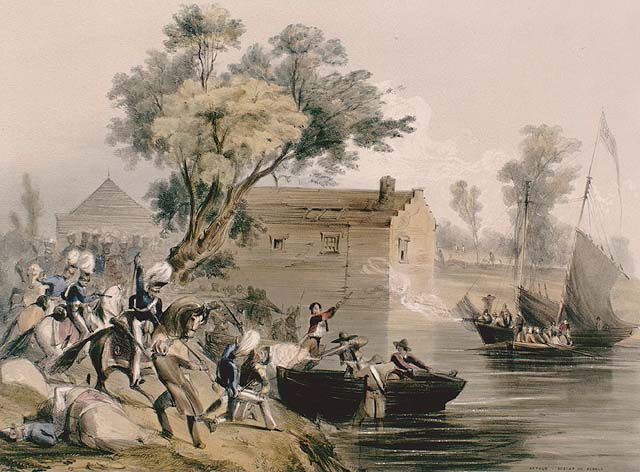

Rebellion in Upper Canada

The 1837 rebellion in Upper Canada was a less violent, more limited affair than the insurrection that same year in neighbouring Lower Canada, although its leaders, including William Lyon Mackenzie, were no less serious in their demands for democratic reform and an end to the rule of a privileged oligarchy ( see Family Compact). The rebellion itself failed, yet its very failure helped pave the way for more moderate and careful political change in British North America.

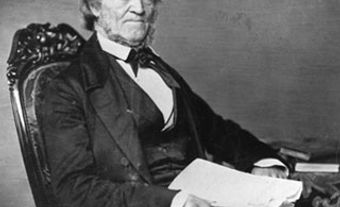

Lord Durham

John George Lambton, the earl of Durham, was a British political reformer who was appointed governor general of British North America by imperial Prime Minister Lord Melbourne to investigate colonial grievances after the rebellions. Durham arrived in Canada in May 1838, but resigned his appointment just four months later, following a dispute with the government in London. Durham returned to Britain and in 1839 completed his Report on the Affairs of British North America, commonly known as the Durham Report.

Durham Report

The Durham Report was controversial and its recommendations progressive for their time. Durham proposed the creation of municipal governments and also a supreme court in the BNA colonies. But his major recommendation was to reunite the Canadas in order to accelerate the assimilation of French Canadians, whom he characterized as a people without a history or a culture. Durham also recommended a reorganization of the system of colonial government, but the British government refused to accept the principle of responsible government. Meanwhile, his long-held plan for the union of all the British North American colonies was dropped because Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were uninterested. (It would take three more decades before Durham's vision of a grand BNA union would be finally achieved through Confederation.)

However, the main recommendation in Durham's Report, the union of Upper and Lower Canada into a single colony, was accepted.

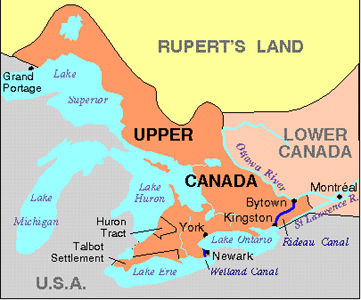

Province of Canada

The united Province of Canada was a 26-year experiment in anglophone–francophone political co-operation. But whereas Lord Durham advocated basing representation on population — counting on British immigration to increase an existing Anglo-Canadian majority — the Act of Union provided equal representation for each of the Canadas in the new Legislature. This occurred even though English-speaking Upper Canada had a considerably smaller population: some 480,000 compared to 670,000 in Lower Canada, of whom about 510,000 were French Canadians. The French element was under-represented from the start.

Yet the device of equal representation had an unforeseen result. The old Canadas, each with its separate history, society and culture, virtually remained equal, distinct sections inside one political framework. They were now Canada West and Canada East geographically, but even the names Upper and Lower Canada survived in popular and some official use. The Act of Union embedded dualism in the very constitution, resulting in dual parties, double ministries and sectional politics.

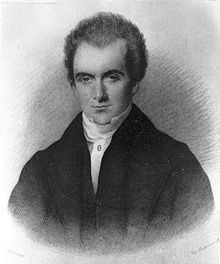

Political Partnership

As the Union began, French Canadians realized that its purpose was to submerge them. But a rising liberal leader, Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine, saw that an alliance with Canada West Reformers could provide a viable means to seek responsible government. LaFontaine believed that with responsible government, French Canadians would share in ruling the United Province, and in maintaining themselves as a people while co-operating with Anglo-Canadian allies. Hence LaFontaine readily responded to overtures from leading Canada West Reformers Francis Hincks and Robert Baldwin to form a united party.

Hincks, a Toronto journalist and shrewd strategist, was already backing Baldwin's campaign for responsible rule that was centered on the British principle of responsible government. Its adoption in Canada would mean that governments would depend on elected parliamentary majorities. Baldwin and LaFontaine built a powerful Reform alliance behind this principle.

In September 1842, they won admission to the government, essentially compelling Governor General Sir Charles Bagot to reconstruct his ministry because of the weight of parliamentary support behind them. (At that time, governors controlled the executive branch of the colonial government and formed Cabinets.)

Responsible Government

A shift in imperial policy finally brought full acceptance of responsible government — in the colonies of both Canada and Nova Scotia . In 1846, Britain's repeal of the corn laws signalled a movement towards free trade, ending a centuries-old pattern of imperial trade controls and protective duties. Britain likewise no longer saw much need to withhold internal self-government from its more politically advanced colonies. Lord Elgin came to Canada as governor general in 1847, instructed to implement responsible rule.

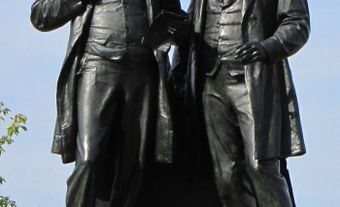

Early in 1848, after Reformers swept elections in both Canadas, Henry Sherwood's Tory-Conservative ministry resigned, and Elgin at once called on Reformers to form a government. Responsible rule was plainly confirmed when in March an all-Reform Cabinet took office under LaFontaine as premier (he had the larger following) with Baldwin as co-premier.

Building Democracy

Responsible government was an important milestone along the road to political autonomy.

The Baldwin-LaFontaine ministry became known as the "great ministry.” Its mandate saw not only the acceptance of the principle of responsible government — a government that is responsible to the people — but a strong record of legislation: the establishment of a public school system, the founding of the University of Toronto and the organization of municipal government.

While responsible government did not transform Canada overnight into a fully developed democracy, it was an important milestone along the road to political autonomy. Most importantly, it provided an opportunity for French Canadians to find a means for survival within the British Constitution. It also displayed, in the partnership and friendship of Baldwin and LaFontaine, a model of collaboration that has been all too rare in politics.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom