The Inuktitut word Inuit is a fairly recent Anglo-French Canadian term and will be used in this article only with reference to the historical and modern Canadian Inuit . Greenlanders, who speak a dialect similar to the Canadian Inuktitut and whose art and artifacts are often almost identical to those found in the Canadian Arctic for the past 4000 years, call themselves Katladlit. Siberian (or Asiatic) Inuit and the Inuit of western and southwestern Alaska call themselves Yuit. They speak a dialect called Yupik, and their art forms, except during Thule culture , bear few stylistic resemblances to those of the Canadian Arctic. Yet there exist strong iconographic and thematic relationships between the art forms, indicating a common ancestry or various cultural interchanges, or both.

Culture Phases

The history of Inuit cultures and the art of the various regions and times can only be understood if the myth of a homogeneous Inuit culture is discarded altogether. Though it has not been possible to determine the exact origin(s) of the Inuit, nor of the various Inuit cultures, five distinct cultures have been established in the Canadian area: Pre-Dorset, Dorset, Thule, Historic and Contemporary.

Pre-Dorset Culture

Pre-Dorset culture developed out of the migrations of people coming from Siberia via the Bering Strait 4000-4500 years ago (see Prehistory). While few art objects of this period seem to have survived, the exquisitely shaped artifacts discovered - particularly the projectile points of harpoon heads and lances fashioned from carefully selected lithic material (stones) - are not merely functional but also of considerable aesthetic value. These objects can in fact be called art even though they lacked imagistic intentions. Through their simple splendour and sensitive craftsmanship they exude the kind of “hunting magic” that perpetuated itself in the succeeding Dorset culture. Pre-Dorset culture lasted for over 1000 years, and it extended into the beginning of the first millennium BC.

Dorset Culture

Dorset culture started to evolve between 700 and 500 BC, and can be called the first Indigenous Canadian Arctic culture. It spread from Coronation Gulf to the bottom tip of Newfoundland and to the entire west coast of Greenland. Several problems have arisen in dating Dorset art, particularly its origins. In the chronology established by Danish archaeologist Jorgen Meldgaard for the Igloolik area, with the highlights occurring between 500 and 1000 CE , art emerges only in the Middle Dorset period, 400-500. Yet the well-known Tyara maskette, made with the same perfectionist artistry that characterizes the best of Dorset art, has been dated to before 600 BC. The explanation may lie in faulty carbon dating, or in the possibility that the maskette is a work from the Pre-Dorset culture that somehow survived. Two Pre-Dorset maskettes from the Igloolik area exist which are similar in appearance.

In Pre-Dorset culture imagistic supernatural objects may have been destroyed or discarded after use, as in other prehistoric and preliterate cultures, and the Tyara maskette could have been an incidental survivor, used or preserved in the later culture. Or perhaps the fine craftsmanship and aesthetic beauty of both the maskette and Pre-Dorset artifacts point to a magical purpose in their creation: that form does not merely follow function but increases efficacy.

High Dorset art appears to be largely magico-religious in its purpose; this appears to be so particularly for the "excaved" (hollowed out and perforated) Dorset bears and falcons relating in shape to harpoon heads. The points of the harpoon heads become the bear heads; the line-hole openings become the front legs attached to the body (or bent backwards in a swimming motion); and the basal spurs become the hind legs (more or less abstracted). The excaved falcons resemble the excaved forms of the harpoon heads and simultaneously the skeletons of birds. The image of disembowelled creatures refers to a ritualistic technique used in shamanic initiations in many parts of the polar world from Siberia to Greenland: the shaman had to think of himself as a durable skeleton, devoid of flesh and blood, so that the helping spirits might consider it worthwhile to come to him. The skeleton designs incised (not etched) into many of the animal carvings have a similar origin and hint at several supernatural meanings: the body as spirit or dematerialized essence, as a kind of ritual form, or as an instrument for magico-religious purposes.

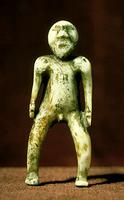

Linear or incised signs on many of the carvings - joint marks and crosses - can also be found in other prehistoric and preliterate cultures. They too seem to have supernatural associations and reinforce the largely magico-religious content of Dorset art. Several other image types exist in Dorset culture, such as the antler or wooden "face clusters," wooden masks, maskettes, human figures, multiple animal images, various birds and land and sea mammals (some with and some without skeleton markings). While their purposes are largely unknown, they do have common characteristics: most are carved in ivory or, to a lesser extent, in bone, antler or wood; with the exception of the face clusters, they are very small - anywhere from 1 to 10 centimetres; all are 3-dimensional, carved with strong or expressionistic features and with decisive strokes of the knife or graver. Except for the wood and antler carvings, they have a remarkably smooth finish despite their small size and expressionist form.

Petroglyphs have been cut in soapstone outcroppings near the sea at Wakeham Bay in Ungava, Québec, faces or maskettes not unlike the previously mentioned face clusters (see Pictographs and Petroglyphs ). The shapes themselves, however, are reminiscent of the Tyara maskette, which comes from nearby Sugluk (Salluit). While this similarity asserts a Dorset origin for the Tyara maskette, it brings the date of its origin further into question.

Thule Culture

Thule culture is much easier to define and to date, but again some anomalies exist. Thule culture migration from northern Alaska into the Canadian Arctic began after 1000 CE and reached eastern Greenland by 1200. Thule is the most uniform of the Inuit cultures, covering as it did the entire Arctic of the western hemisphere, including the eastern tip of Siberia. That manifest uniformity was responsible for giving the Inuit the appearance of homogeneity, which is misleading except for Thule culture artifacts. Thule art across the Arctic was not as uniform as many social scientists once believed, and therefore the less conspicuous art forms of the Thule people in comparison to powerful Dorset and Old Bering Sea art of Alaska have led to the revision of many misjudgements by a new generation of archaeologists.

The Thule people, whose pre-Thule ancestry can be traced to southwestern Alaska but who had evolved into their new culture type in northern Alaska, were themselves the true ancestors of the contemporary Inuit. In Canada, however, the art forms of these two cultures reflect little of this relationship. This is in contrast to the Thule art tradition in Alaska, which continued well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The most frequent types of Thule art in Canada are combs, needle cases and "swimming figurines" (birds, spirits and humans), as well as various kinds of utensils and female effigies. In contrast to Dorset art, which had hardly any stylistic similarities to contemporaneous Alaskan art forms, Canadian Thule art is strongly dependent on Alaskan prototypes of the same culture and period.

While Dorset art, in its stark and expressionist form and technique, has a definite masculine quality, which in form and content relates to weapons and tools used by males, Thule art relates in almost every detail to female images, forms and uses. Utensils such as combs, thimble holders, needle cases, bodkins and pendants are obviously women's practical and decorative equipment; the "swimming figurines" too are either female representations or relate to them in their shape. They are identical in their basic structure, with only the upper parts of their bodies shown; the parts underneath the waterline, not being visible, are therefore not shown. These figurines obviously had a common origin, probably as amulets or for similar magico-religious purposes. It is therefore difficult to believe that these carvings were gambling pieces (tingmiujang), though they were the prototypes for the gambling pieces used after the breakup of traditional Thule whaling culture in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Besides being small, elegantly shaped and often beautifully decorated, almost all female figurines and statuettes of Thule art are faceless, in contrast to the Dorset figures, with their strongly expressed mostly male faces. The two notable Thule exceptions with beautifully carved faces are a comb from the Pelly Bay region and a marrow fork (or perhaps a bodkin for tents or umiaks ) from Strathcona Sound. There are a few other carvings with vaguely incised faces and also a few stick figures on combs, as well as a unique bow drill from Arctic Bay.

The Historical Period

The historical period begins with the demise of Thule culture, as the climate became colder and the whales disappeared, and the coinciding arrival of the white man in the Arctic in the 16th century. The unified art style also broke down, though some Thule effigies persisted into the 20th century, such as the swimming figurines that turned into gaming pieces and the female statuettes that turned into dolls. Certain women's utensils also continued, but carved in much cruder and less stylish forms.

At the start of the 19th century, the dolls, toys and animal carvings that were exchanged with whalers, sailors and explorers (who had then begun to visit on a more or less regular basis) gradually turned into trade and souvenir art, often quite exquisite. In fact, the trade carvings display a much greater skill than carvings made by the Inuit for themselves. By 1920 trade art (which was largely made out of ivory or bone) had lost all of its magico-religious meanings, and many carvings became replicas of tools and weapons of both Inuit and white men. In several areas liturgical art (replicas of Roman Catholic figurines) were produced regularly, as were inlaid or incised cigarette boxes, match holders, cribbage boards and sailing vessels. Even though the Inuit had lived a largely traditional lifestyle before WWII, their art forms - but not the techniques or processes for making their objects pinguaq or "toy-like representations" - became increasingly oriented to the white man's tastes and uses.

The Contemporary Phase

The contemporary phase was a logical outcome of the transitional and acculturated art forms of the historic period, and coincided with the gradual "opening up" of the North after WWII, with the launching of the DEW Line (Distant Early Warning system) and, most of all, with the emerging interest of Western nations in the art and culture of preliterate societies. Largely owing to the insights and promotional energy of James A. Houston , a young artist from Toronto, Inuit art as we know it today came into existence in 1948-49. He encouraged the Inuit to use their "natural talents" in creating art objects to help solve their economic problems. In this regard they were assisted by the Inuit Co-operatives .

Soapstone and ivory carvings from Povungnituk and Inukjuak (Port Harrison) in Québec were the first art forms to appear for sale in the south. Salluit (Sugluk), Cape Dorset and Repulse Bay followed, and soon the entire central Arctic was covered, from Kugluktuk to Arctic Bay, with other areas to join later in the 1960s and 1970s. The whole enterprise resulted largely from the support Houston and the Inuit received from the federal government, the former Canadian Handicrafts Guild and the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1957-58 Houston also introduced printmaking into Cape Dorset; in the next 20 years, this craft spread to Povungnituk, Holman [Ulukhaktok], Baker Lake, Pangnirtung and, to a lesser extent, into several other arctic communities, including Clyde River.

In the new carving activities the emphasis is largely on soapstone and serpentine, which have become increasingly scarce, and stone is often imported from the south. Stone differs greatly from the organic materials used in prehistoric and historic times. Ivory is still used in several areas, especially at Pelly Bay and Repulse Bay, where miniature carvings predominate. Beached whalebone was first used at Arctic Bay but had largely disappeared by the mid-1970s. Instead, large whalebone fragments taken from prehistoric Thule culture sites became extremely popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, especially at Pangnirtung and Spence Bay. The use of this material had steadily declined, largely because of the US embargo on endangered species.

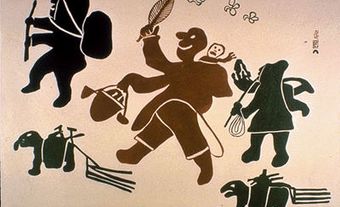

Though carving is still the largest art activity, Inuit printmaking has become the one providing the greatest financial returns for southern collectors and "art investors." Drawings and paintings are also produced in quantity, but they have never enjoyed the popularity of the prints. Every printmaker draws, but only a few artists paint (notably Pudlo Pudlat from Cape Dorset and Davie Atchealak from Pangnirtung). Wall hangings (embroidered, appliquéd or woven) are probably the most impressive of the newer two-dimensional art forms but, though highly valued by connoisseurs, they have not achieved the wide acceptance of the prints.

The new art forms do not have the uniform style and content characteristics found in Dorset and Thule art, but rather exhibit local and individual characteristics. Inuit art is easily recognizable as such, but only because of a predictable subject matter or a definite personal or local style. Most Inuit art shares a predominantly narrative or illustrative content that depicts the traditional lifestyle and techniques for survival, the animals of the North, the spirits of those animals or the shamans and mythologies which were the links to that spirit world. But here the similarity ends. In Baker Lake, for instance, Vital Makpaaq and David Ekoota Ikutaaq have initiated a style of massive stone carving, whereas Luke Ikseetaryuk developed out of antler characteristic images and compositions of his own which have no stylistic relationship to the stone carvings. Baker Lake printmakers and producers of wall hangings such as Jessie Oonark, Marion Tuu'luq, Luke Anguhadluq, William Noah and Simon Tookoome also have their own individual styles, as have at least 10 others.

A similar situation exists at Cape Dorset, where all the well-known artists are highly individualistic, including carvers Aqjangajuk Shaa , Qaqaq Ashoona , Kiawak Ashoona , Kumwartok Ashoona, Latcholassie Akesuk, Osuitok Ipeelee and Pauta Saila , and printmakers Parr , Pitseolak Ashoona and Pudlo Pudlat. Collectively, however, they are typical of Cape Dorset art, and it is possible to speak of a Cape Dorset style with its definite and crisp shapes and often quite original ideas.

In Povungnituk, too, the principal artists all have their own style and subject matter. The stylistic individuality of artists such as Alasua Amittuq Davidialuk , Joe Talirunili and Josie Papialook (Paperk/Poppy) is noticeable in both carvings and prints. These 3 artists were seldom imitated, but ideas of Charlie Sivuarapik , Levi Alasua Pirti Smith and Eli Sallualuk were followed by many of the lesser artists. These multiple Povungnituk styles have one common feature - high finish and craftsmanship. This characteristic applies to both the highly representational and the fantastic art of Povungnituk, but not to the works of Davidialuk, Talirunili and Papialook which, though also narrative, have retained a definite feeling of simple rawness and forceful, personal expression. Comparisons could be drawn between Pelly Bay, Repulse Bay and Arviat (Eskimo Point), all of which have styles that could easily be related to folk art , but here too there are many subtle and individual exceptions. In general, Arviat carvings of stone and antler are carved more crudely than the stones and ivories of the other 2 communities, yet John Pangnark’s abstract work from Arviat is extraordinarily elegant and sophisticated. Artists using whalebone, especially the vertebrae, which have naturally fantastic shapes, have a certain advantage, leading often to unusual sculptures. This applies particularly to Talovoak (formerly Spence Bay) artists such as Karoo Ashevak and Sakkiassee Anaija, but interesting work has also been coming out of the eastern and northern regions of Baffin Island.

The contemporary phase is evolving rapidly with changing styles and imagery, especially in the 3 Kitikmeot settlements at the most westerly side of the Central Arctic. There, among the most prominent artists, are Nick Sikkuark and Judas Ullulaq (at Gjoa Haven), Charlie Ugyuk (Taloyoak), and the late Augustin Anaittuq (Pelly Bay). Among the several major Inuit artists who, now middle-aged, have moved to the southern parts of Canada, are Manasie Akpaliapik (Toronto), and the brothers Abraham Anqhik (Salt Spring Island, BC) and David Ruben Piqtoukun (Toronto). Of the younger generation of contemporary Inuit artists who have developed reputations in the international art world are the late Annie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona.

Collectors and museums have started to pay very high prices for the work of these artists but even more so for the older, more "classic" carvings and prints. Yet while the production of the "new" art has increased noticeably, it unfortunately has been accompanied by an overall decline in quality. While there are still an astonishing number of very good artists producing a fair amount of outstanding work, the collective quality standards need careful watching. The better Inuit artists are largely aware of this dilemma. However, only the local northern buyers - the co-operatives, the North West Company and several individual wholesalers who purchase the work directly from the artists - can actually exercise some degree of influence over the quantity and quality of the production - or over-production - of this important aspect of Canadian art.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom