Canada has been involved in various wars from the beginning of its colonial history. Just as the nature of these wars has changed over time, so, too, has their effect on Canadian women. Women have actively participated in war, from nursing and munitions manufacturing during the First and Second World Wars to the increasing involvement of Canadian women in the military.

War has impacted Canadian women’s lives in different ways, depending on their geographical location and racial and economic status. Pre-20th-century conflicts had a great impact on women in Canada, especially Indigenous women, whose communities could be dispossessed and devastated by colonial militaries. Women were interned in Canada during wartime — that is, detained and confined — because their background could be traced to enemy states.

While some women have been traumatized profoundly by Canada’s wars, others have indirectly benefited from them. Women have often assumed traditionally male work during wartime — a pattern that has, in some cases, contributed to the advancement of women’s rights .

(See also Women in the Military; Wartime Home Front.)

New France and British North America

Women who accompanied the French and English military forces of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries cooked, laundered, sewed, and tended to the sick and wounded. Some protected their property from marauders and prepared ammunition, food and medicines.

In mid-17th-century Acadia, the wife of Charles de Saint-Étienne, Françoise-Marie Jacquelin (better known as Madame de La Tour), took command of her husband’s colonial army corps in his absence and defended Fort La Tour against a rival militia (see Civil War in Acadia). Similarly, in 1692, the 14-year-old Marie-Madeleine Jarret de Verchères played a decisive role in defending Fort Verchères from Haudenosaunee raiders. During the War of 1812, Laura Secord famously walked more than 30 km to warn the British military of an impending attack.

During the 1885 North-West Resistance, women were admitted officially to the military for the first time, as nurses (see Nursing Sisters). Civilian nurses also accompanied the Yukon Field Force during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, as well as the Canadian contingent in the South African War (1899–1902).

(See also Nursing Sisters and the Costs of War on Women.)

Expansion of Women’s Wartime Roles in the 20th Century

Into the 20th century, factors like the distance of conflicts and restrictive ideas about women’s abilities combined to prevent direct participation by women as combatants. Nonetheless, during both the First and Second World Wars, women organized for home defence, outfitting themselves in uniforms, and training in rifle shooting and military drills.

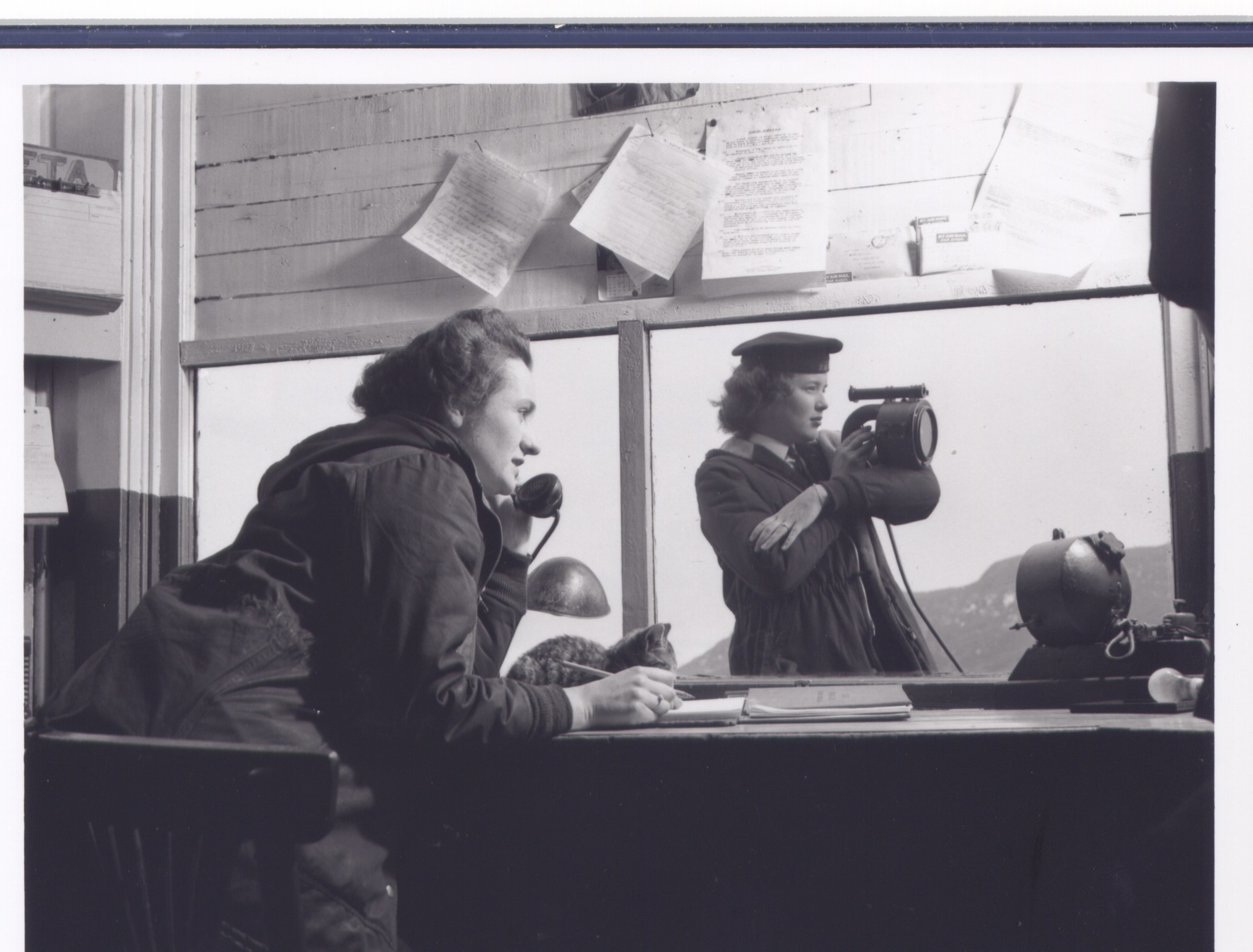

The first two women’s services were created as auxiliaries to the air force and the army in 1941. Some 50,000 Canadian women eventually enlisted in the air force, army and navy. While the Royal Canadian Air Force Women’s Division members were initially trained for clerical, administrative and support roles, they eventually came to work as parachute riggers, laboratory assistants, and within the electrical and mechanical trades.

The Canadian Women’s Army Corps followed the same path, with its members starting out as cooks, nurses and seamstresses, but later becoming drivers and mechanics. The third women’s military corps, the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS, or “Wrens” informally), was established in 1942. Growing wartime bureaucracy opened the way for women as officially recognized members of the armed forces outside of nursing, and many women in the service gained employment in clerical positions as stenographers, switchboard operators and secretaries. Many Wrens were involved in intelligence work during the war. Although women did not serve in combat, members of the RCAF Women’s Division, CWAC and WRCNS were posted overseas during the Second World War.

As in previous conflicts, thousands of Canadian nurses served during the world wars. Female physicians were also admitted to the armed forces for the first time during the Second World War. (See Jean Flatt Davey.) Many of these nurses and doctors served overseas, some of them in direct support of Allied campaigns in North Africa, Italy and Northwestern Europe.

Suffrage

In 1917, amidst the tremendous reconfiguration of labour practices on the home front, the movement for women’s suffrage won a major victory with the passage of the Wartime Elections Act, which granted some women the right to vote in federal elections. Suffrage at this time was limited to women working in the armed forces and the wives, mothers and sisters of soldiers overseas. At the same time, however, the Act revoked voting rights from Canadian citizens of enemy-alien birth who were naturalized after 1902. Today, most historians view the Act partly as the product of women’s growing presence in the public sphere and partly as a move by Prime Minister Robert Borden to bolster electoral support for his government (see Election of 1917).

DID YOU KNOW?

The term enemy alien referred to immigrants from countries that were legally at war with Canada. During the First World War, Canada interned 8,579 enemy aliens in 24 receiving stations and internment camps from 1914 to 1920. Those interned included Ukrainians, Germans, Turks, Bulgarians and people of Austro-Hungarian origin.

Wartime Roles on the Home Front

Another important role for women during wartime, especially the Second World War, consisted of code breaking and espionage. The Canadian government recruited members of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service and the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, among others, to break coded messages. They worked in British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Ontario, including at Camp X.

While a few women had produced ammunition in factories during the South African War, during the First and Second World Wars they entered the munitions industry en masse. According to the Imperial Munitions Board, about 35,000 women worked in munitions factories in Ontario and Quebec during the First World War. In 1943, approximately 261,000 women were involved in the production of war goods, accounting for more than 30 per cent of the aircraft industry, close to 50 per cent of the employees in many gun plants, and a distinct majority in munitions inspection.

Women also worked to ensure a thriving domestic economy. During the First and Second World Wars, they produced and conserved food; raised funds to finance hospitals, ambulances, hostels and aircraft; and volunteered their services inside and outside the country. Many women also joined such public service organizations as the Federated Women’s Institutes of Canada, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, the Young Women’s Christian Association and the Canadian Red Cross Society.

Whatever the conventional role for women in the social order, war required the full scope of Canada’s human resources. At the same time, the temporary nature of women’s contributions during the First and Second World Wars ensured that their wartime efforts did not challenge the established system and that they reverted to conventional female roles after hostilities ended. In war, women’s labour was essential, but in peace it was expendable.

(See also Wartime Home Front.)

Women in the Canadian Armed Forces

Despite women’s contributions to Canada’s military efforts in the 20th century, they were not allowed full entry into the armed forces until the late 1980s. Canada opened all military positions to women in 1989 (except for submarines, which admitted women in 2001). By 2001, women made up 11.4 per cent of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF).

CAF recruitment and retention of men and women slowed during the early- to mid-2010s — and full- and part-time membership fell short of targets. The recruitment of women stagnated, and women left their positions at a slightly higher rate than men. In response, the CAF established a recruitment and retention strategy that sought to increase the number of female personnel by one per cent annually, with a goal of reaching 25 per cent representation by 2026.

By February 2018, 15.3 per cent of CAF personnel, 4.3 per cent of combat personnel and 17.9 per cent of all CAF officers were women. Of the 14,434 women serving, 7,408 were in the Army, 2,856 in the Royal Canadian Navy and 4,160 in the Royal Canadian Air Force. A year later, 4.8 per cent of combat personnel in the regular force and primary reserve were women. By February 2020, women made up 16 per cent of CAF personnel: 19.1 per cent of officers and 15.1 per cent of non-commissioned members. The percentage of women was highest in the navy (20.6 per cent), followed closely by the air force (19.8 per cent). Women comprised 13.5 per cent of the Canadian army in 2020.

The percentage of women in the CAF has increased slightly since 2020. As of May 2023, women comprised approximately 16.5 per cent of the regular force and primary reserve in the CAF: 19.6 per cent of officers and 15.4 per cent of non-commissioned members. Women made up 20.7 per cent of the navy, 20.3 per cent of the air force, and 13.9 per cent of the army at that time.

(See also Women in the Canadian Armed Forces.)

Women and the Anti-War Movement

Canadian women have impacted warfare as much as warfare has impacted them. Some have significantly affected the character of the Canadian military by climbing its ranks and promoting its activities, while others have joined pacifist and anti-war movements that have sharply criticized the military. Many Canadian women have undertaken leading roles in the struggle against war. This was especially the case during the First World War, when women across Europe and North America organized for peace on an unprecedented scale.

Yet the war also had a very divisive impact on Canadian women. A number of mainstream women’s organizations, such as the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC) and the National Committee of Women for Patriotic Service (NCWPS), openly or tacitly supported the war. Other women contested the war at its outset but became increasingly convinced of its necessity. Prominent suffrage leaders Nellie McClung, Emily Murphy and Flora MacDonald Denison, for instance, all held to their longstanding pacifist beliefs when war broke out in 1914, but later changed their position as they became convinced that Germany’s attacks on Britain could only be stopped through military defeat.

In 1915, prominent American reformer Jane Addams organized the Women’s Peace Conference at The Hague. Addams had invited the NCWC and the NCWPS, but both declined. A handful of Canadians did ultimately attend as independent delegates, including Julia Grace Wales and Laura Hughes. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was founded by women active in the women’s suffrage movement in Europe and North America who attended the conference at The Hague. These women wished to end the First World War and seek ways to ensure that no more wars took place.

In the subsequent century, the alignment of the pacifist movement and nationwide women’s activism was never again quite as strong as it was during the First World War. Nonetheless, Canadian women did play a leading role in the struggle for nuclear disarmament in the 1960s, which gave birth to the Voice of Women (now the Canadian Voice of Women for Peace). In the early years of the 21st century, thousands of women across the country also mobilized to prevent Canada’s involvement in the 2003 United States-led invasion of Iraq.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom