Nordicity

Nordicity is a wide concept developed in Canada from the 1960s that refers to the perceived, real or even imagined condition of high-latitude regions. It deals with a large variety of issues taken from both the natural and the human world that may lead to the combined understanding of facts, ideas and interventions of these northern lands.

Beyond the purely intellectual dimension of this concept, the approach examines the arrival of technological applications in the field of living conditions, for instance, and encourages the individual to evaluate his or her own activities. Nordicity takes the NORTH as an object of study in its entirety rather than focusing on specific fields of research. Its tools of research do not bypass any analytical approaches of related sciences such as climatology, bio-geography, behavioural sciences, political economics and other sciences. Both French and English dictionaries define the word as canadianism. In this essay, we speak of the circum-terrestrial dimension of nordicity in terms of Canada only.

Definitions of the North are primarily dependent on the criteria chosen to make up the definition. Originally the Arctic was defined simply as a region of polar night or day, with a frozen subsoil and without trees or agriculture. The nordicity concept developed a more encompassing definition which included physical and human geography.

Nordic Index

A nordic index was devised for calculating and quantifying the number of "polar values" (called VAPO) and establishing the nordicity of a space or phenomenon. This index is based on 10 criteria, each expressed on a scale of 0-100. The criteria include one locational variable and 5 natural and 4 human factors. For location, 45°north latitude is assigned 0 VAPO; 90° north, 100 VAPO. Summer-heat values range from more than 150 days above 5.6°C, 0 VAPO, to 0 days, 100 VAPO. Similarly, with annual cold, 550 degree days below 0°C is assigned 0 VAPO; 6650 days, 100 VAPO.

The human factors are more difficult to quantify but, for example, degree of economic activity ranges from "interregional centre with multiple services, heavy investment," assigned 0 VAPO, to "no production, none foreseen," 100 VAPO.

A table outlining these variables allows an arithmetic evaluation of the nordic character of cold regions and facilitates understanding of the factors most important to this evaluation. Another useful tool is the isonord, a line on a map joining points that have equal polar values.

Southern Limit

The nordicity evaluation process provides information for the task of fixing the southern limit of the North. Formerly, that limit was determined by a single factor, eg, an isotherm (10°C in July), a latitude (often the ARCTIC CIRCLE), an administrative boundary (60° north latitude), or a topographic feature (Hudson Strait).

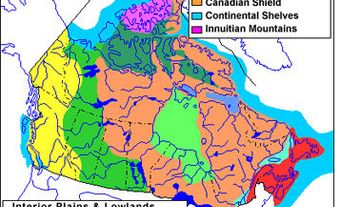

No one factor is now considered definitive, but nordicity does increase abruptly above isonord 200, suggesting a fundamental break running across Canada. This isonord runs along the southern edges of the LONG RANGE MOUNTAINS in Newfoundland, sweeps along the northern shore of the St Lawrence River and runs north of the Saguenay depression in Québec and Lake of the Woods, Ontario. It passes through Lake WINNIPEGOSIS, Manitoba, and touches Montreal Lake, Saskatchewan.

In Alberta, it runs north of the agricultural area of the Peace River country to the oil and natural gas fields of Fort St John, BC. In BC, the CORDILLERA complicates the determination of the true North. Pockets of discontinuous PERMAFROST lodge in the summits of peaks in southern parts of the province; temperate conditions are found in the bottoms of northern valleys. However, considering all criteria and despite the anomalies, the boundary of the cordilleran North can be fixed between 53° and 55°north latitude.

The nordicity index and the zones that it defines can have several uses. Apart from setting the North's southern limits, it allows subdivision of the polar world itself into zones. Moreover, it has been used for the classification of documents, construction of a scale of workers' allowances, analysis of the evolution through time of tourist potential, estimation of the cost of services, and for a study by the Fisheries Board of Canada. This index would provide a more realistic basis for determining royalty zones in the development of northern PETROLEUM than does the simple division by latitude now used.

Canada's ecological limit has been fixed by the federal government at 200 nautical miles (370 km) from shore in the Arctic Ocean. Thus the nordic political territories include parts of 7 provinces, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Including the waters within the North and the oceanic water belt, the nordic space occupies about 70% of Canada's territory. This seems a more exact estimate than the official 39%, which includes only the landmasses and fresh waters of the Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories.

Number of Northerners

Inside this immense zone (one-third of which is water), the population in 1941 was around 145 000 resident inhabitants; by 2000 the population is expected to be 500 000. Canada's nordicity is more severe than that of Scandinavia or even Siberia, a fact that discourages settlement. The Canadian North consists of hundreds of small settlements scattered over a larger territory than Europe. A web of technical and social services keeps these isolated worlds in touch with the South.

Northern Zones

The idea that the North could be divided into broad east-west bands appeared repeatedly in works of the mid-19th century. For example, in 1832 Joseph Bouchette divided western Canada as follows: everything south of 56°north latitude, everything between 56° and 65°, everything from 65° to the Arctic Ocean. Thematic divisions between BOREAL FOREST and TUNDRA, between subarctic and arctic, between seasonal and permanent pack ice, between regions of partial and total light, between aboriginal and Inuit lands, all reflect other zonal gradations. The regional subdivisions of the North include 3 major regions, the boundaries of which do not follow lines of latitude.

Historical Nordicity

Like any region defined by natural and psychological factors (the latter heavily influencing settlement), the North has varied in size over its history. Even if, in the course of a generation, the boundaries of permafrost, sea ice and boreal forest barely change, the factors involved in settlement and abandonment of habitations, in economic development and in the creation of mental perspectives are constantly evolving.

At the beginning of the Age of Discovery, Canada and Newfoundland were considered all north because of the severe winter conditions. Later, as Morris Zaslow has noted: "In the immediate post-Confederation period, anything beyond Lake Nipissing was termed North." In Québec and central Labrador, iron-ore exploration and hydroelectric development have caused this outland to lose some of its former polaricity.

According to the nordic index, in 1941 unexploited central Québec and Labrador had 533 VAPO; 25 years later, 295. Settlement caused that evolution. Thus, in the last century, as a result of a redefinition of zones, the real Canadian North has become less widespread and the average nordicity of the country has become lower. A quantitative national denordication of approximately 25% has occurred.

Between 1881 and 1971, the resident population of the North multiplied sevenfold (43 060 to 292 702). The present nordic space, especially the Middle North, has been overrun by Canadian and foreign immigrants, but this penetration has been uneven in time and space. The movement had begun by 1881 (census year). At that time, the future province of Newfoundland and Labrador accounted for more than half of all the non-native residents in the Canadian North. By 1910, 8000-10 000 northerners (non-native and native) lived in the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec, but the influx only became important in the course of the 20th century.

Between 1911 and 1941 settlement patterns once again modified the regional pattern. As a result of mineral exploration and agricultural development along the pioneer fringes of western Canada, Alsama (Alberta-Saskatchewan-Manitoba) had 50% of the nordic population and became the main nordic mega-region; Manitoba stood first among the provinces. Since the mid-20th century, a strong natural increase in the indigenous population and increases in governmental administration and oil exploration have caused an increase in Canada's northern population. Thus, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Newfoundland and Labrador have experienced increased growth percentages. In 1971 Alsama was still first, followed by the territories (counted as one). BC, Ontario and Québec accounted for only 22% of the nordic population of the country.

Developmental Nordicity

The North has known at least 5 developmental visions since Martin FROBISHER's mining projects of the 16th century. An initial period of optimism, based on the hope of discovering a NORTHWEST PASSAGE, ended when that proved unprofitable. The resulting view, that the North was almost totally useless, led to suggestions that nordic lands should be sold or given away. A more recent political vision is of the North as an unlimited reservoir of natural resources. The final visions are an ideology of nondevelopment ("Freeze the Arctic") and one of integrated planning that respects nordic culture.

Conceptually, at least 2 categories of nordicities of exploitation must be identified: nordicity of use and normative nordicity. The first can be seen inductively through examination of the activities of entrepreneurs and employers who lack specialized training for work in the North. Clearly, the nordicity of use has influenced economic and political growth both in private and government frameworks. Many activities in the North seem to have been determined by southern Canadian interests, by federal jurisdiction over the territories, and by the inadequate appreciation of native ethnicity. These activities have resulted in exploitation poorly adjusted to northern conditions.

The second is normative nordicity, corresponding to the vision of an ideal and theoretical good based on the triple principle of cultural, ecological and regional respect for the North. Its objective is a coherent plan, not a laisser-faire philosophy.

These 2 developmental nordicities are widely separated ideologically. Happily, this gulf has been somewhat diminished by a series of measures: recognition of certain native rights (eg, in the JAMES BAY AND NORTHER QUÉBEC AGREEMENT, 1975; and the Inuviatuit Agreement, 1984); development technologies that increasingly respect arctic regions (CONSTRUCTION, resource extraction, TRANSPORTATION); changes in administrative policies; educational programs that are more appropriate to northern cultures; and native political activity.

Thanks to an increasingly developed multidisciplinary study of all aspects of the North, a new political economy of the North with a nationalist tone and a new GEOPOLITICS encompassing Canada as a whole are developing. The process of the entry of the North into Canadian affairs is far from complete.

Autochthonous Nordicity

Theoretically, evolutionary change without the domination of one of the parties would end in normal interethnic relations. At the end of a process of intercultural convergence, good will, understanding and tolerance, the 2 autochthonisms, that of the indigenous peoples and that of everyone else, would lead to an arrangement of coexistence, or cohabitation, resulting in a completely new national state. This concept helps to explain the self-determination efforts of indigenous peoples of the North - as well as other parts of Canada - and the creation of NUNAVUT.

A starting definition of autochthonism could be as follows: the politico-cultural systems of a nation-state and of its citizens, taking into account the ancestral and collective realities of the descendants of the populations living in the country at the time of the earliest contacts.

Here are some brief comments on the defining terms. While the realities of the indigenous peoples cannot be limited to the "earth" aspect, this concept does appear to be basic to LAND CLAIMS. The subject concerns geography, culture and law. The first involves not only the emerged rock and soil masses (mainland regions and islands), but also inland, estuarine and marine waters, and other natural components such as fauna, flora and air.

The qualifier "ancestral" eliminates any claim of this sort to these lands which other citizens, whether descended from the colonists or from immigrants who came later, could imagine they might have; this is the area of clearest distinction between autochthons and immigrants.

The use of the term "system" calls for a set of integrated actions. The plural indicates that the autochthonistic administrations to be recognized by the higher authorities will include management variants from one culture to another. For example, the autochthonism of salmon river native peoples, both Pacific and Atlantic, will be reflected by a political formula which differs in part from that of Inuit of the migrating caribou.

The term "collective" refers to a legal concept other than that of individual rights so dear to the government charters; this concept of "rights of peoples" also differs from those of the rights of state, international rights and the rights of specific social groups.

Finally, the expression "nation-state" in the singular reflects the fact that changes will be made within constituted countries, thus the creation of many sovereign countries, one for each native group, is not contemplated.

See alsoABORIGINAL RIGHTS; RESOURCE MANAGEMENT; NORDICITY: TABLE.

Middle North

Bounded by isonords 200 and 500 VAPO, the region has a subarctic climate, stretches from Labrador to the Yukon and includes many lakes and bogs. It has been the domain of pioneering thrusts, of "vertical" corridors for the extraction of MINERAL RESOURCES and the production of HYDROELECTRICITY. The Middle North includes about 90% of the North's permanent inhabitants. About 85% of the Middle North lies within provincial boundaries, a fact that receives insufficient political attention. Examples of mean nordicity include Churchill, Man, 450 VAPO; Dawson, Yukon, 435; Yellowknife, NWT, 390; Cassiar, BC, 377; Labrador Sea, Nfld, 297; and Red Lake, Ont, 220.

Far North

This spans the area between 500 and 800 VAPO. Natural factors (eg, limited summer heat and tundra landscape) and human factors (eg, presence of Inuit and rarity of major RESOURCE exploitation) again combine to express a total zonal situation. Being partly composed of interconnected bodies of water, the Far North allows a certain amount of penetration by boat in summer. Since only around 30 000 inhabitants live in this quarter of the Canadian landmass, the ecumene of primary and tertiary activities is extremely extensive.

The Far North is an arctic land that has few residential oases and a public finance deficit. Its population, unlike that of the Middle North, consists mostly of indigenous people. Examples of this nordicity include Resolute; Nunavut, 775 VAPO; Old Crow, Yukon, 624; Hudson Bay (centre), 622; and Aklavik, NWT, 511.

Extreme North

This hypernorthern region, which covers less than 10% of Canada's landmass, includes the top of the ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO cone and heavily iced marine waters with a nordicity in the 850 VAPO range. It is a region of ice (on land, at sea and in the depths). The Extreme North is almost devoid of settlements, with the exception of a few non-native outposts such as Alert, Nunavut. Government expenditure is usually larger than private. Alert has 878 VAPO; Eureka, Nunavut, 857.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom