Joseph-Edmond-André Laurendeau, French Canadian journalist, politician, playwright, and co-chairman of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (born 21 March 1912 in Montreal, QC; died 1 June 1968 in Ottawa, ON). A lifetime French-Canadian nationalist, he helped prepare the way for Quebec's Quiet Revolution by redefining nationalist aspirations for an urban and industrial society.

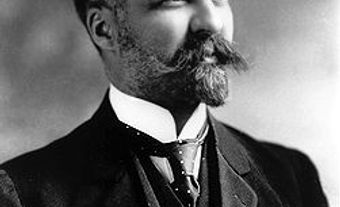

André Laurendeau (left) and Davidson Dunton (right), cochairs of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism

Background and Early Activism

André Laurendeau was the son of music professor Arthur Laurendeau and pianist Blanche Hardy. Born in Montreal, he completed his classical education at Collège Sainte-Marie in Montréal. Afterwards, he pursued his graduate work in literature and history at the Université de Montréal. There, he was influenced by Lionel Groulx who was a prominent intellectual figure.

In the early 1930s, he was briefly involved and led the nationalist intellectual youth movement, Jeune-Canada. The group, however, also openly promoted anti-semitic discourse while downplaying the persecution of Jews by Nazi Germany. It’s only in 1962 that Laurendeau would publicly confess in Le Devoir his involvement with Jeune-Canada and renounce his anti-semitic views.

In 1935, Laurendeau spent 2 years in France taking courses at the Sorbonne, the Collège de France and the Institut catholique. While in Europe he came to embrace the social Catholicism and the personalism of Emmanuel Mounier, Jacques Maritain and Étienne Gilson.

André Laurendeau returned home to Canada and became critical of the concept of political independence for the French-Canadian nation. He was determined to reorient French Canadian nationalism toward socioeconomic issues. Between 1934 and 1942, Laurendeau was a contributor and then an editor for L'Action nationale where he advocated for French-Canadian nationalism.

Political Career

During the Second World War, André Laurendeau joined forces with other nationalists to create the Ligue pour la défence du Canada. The Ligue had been founded to fight against Conscription during the 1942 plebiscite called by Prime Minister Mackenzie King. The league was successful in swaying French Canadians — over 80% of whom voted against conscription.

In the wake of the Ligue’s success, a nationalist third party was created in the fall of 1942. The Bloc Populaire fought against the threat of conscription and demanded greater equality for Francophones in the federal system. Laurendeau was selected as provincial leader of the Bloc in February 1944. He was one of the 4 Bloc members to win election to the Québec Assembly in 1944. He denounced the centralist economic and social policies of the federal government. He also called upon the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis to make provincial autonomy meaningful by implementing long overdue socioeconomic reforms.

Later Publishing Career

In September 1947, André Laurendeau resigned as leader of the Bloc Populaire and, at the invitation of his friend and publisher Gérard Filion , joined the editorial staff of Le Devoir. He became editor in chief in 1958, a position he retained until his premature death in 1968. Between 1948 and 1954, he also resumed the functions of director of L'Action nationale, which he infused with a new sense of direction, and attracted a new generation of contributors and readers.

Along with his nationalist colleagues, Filion, Jean-Marc Léger and Pierre Laporte, he fought the politically and socially regressive regime of Duplessis The group turned Le Devoir into an effective forum for criticism. Laurendeau called for a redefinition of traditional French Canadian nationalism to reflect the problems and aspirations of an overwhelmingly urban and industrial society. This new form of nationalism was adopted by the Québec Liberal Party of Jean Lesage prior to the 1960 provincial election in which the Union Nationale was defeated.

In addition to his other work, Laurendeau was a radio and TV personality, and wrote articles, TV dramas, a play, Deux femmes terribles (1961), and a novel Une Vie d'enfer (1965).

The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism

Fearing the political and social implications of the rise of separatism in Québec after 1960, Laurendeau called upon the Diefenbaker and the Pearson governments to investigate the crisis in Québec-Ottawa relations. Prime Minister Pearson responded by creating in 1963 the B&B Commission with Laurendeau and Davidson Dunton as co-chairmen. Until 1968, Laurendeau pursued diligently, but with a growing sense of despair, the challenge of finding a long-term solution. One which would provide constitutionally entrenched equality for the French Canadian majority of Québec and the francophone minorities outside Québec.

His fellow commissioners, reflecting the divisions within Canadian society at large, could not come to terms with the constitutional implications of linguistic duality and cultural pluralism. Consequently, the final volume of the report never materialized. The country did respond to the crisis by making room for French Canadians at the federal level through the implementation of the 1969 Official Languages Act. However, Laurendeau would not live to see the implementation of official bilingualism in Canada; in 1968, he died in Ottawa at the age of 56. (See also Biculturalism.)

Honours

- Member of the Royal Society of Canada

- Member of the Académie canadienne-française

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom