Industrialization is a process of economic and social change. It is one that shifts the centres of economic activity onto the focus of work, wages and incomes. These changes took two forms in Canada, beginning in the 19th century. First, economic and social activities were transformed from agriculture and natural resource extraction to manufacturing and services. Second, economic and social activities shifted from rural cottage industries to urban industrial pursuits. Industrialized production took place under the privately owned factory system, in which a larger proportion of the population expected to be wage earners for all of their working lives. Therefore, industrialization brought major changes, not only in work and the economy, but in the way society was organized and in the relations among different groups in society. Although it has evolved over nearly two centuries, the process of industrialization is considered revolutionary — as the term Industrial Revolution suggests — because it marked the shift from feudalism to capitalism, and from agriculture to manufacturing and services — changes that fundamentally altered human existence.

This is the full-length entry about Industrialization in Canada. For a plain-language summary, please see Industrialization in Canada (Plain-Language Summary).

International Context

While British North America experienced its own industrialization, international developments shaped the way Canadians first experienced it. Before Confederation, Canada was shaped by its mercantilist relationship to Great Britain. Mercantilism functioned on the premise that colonies would provide raw materials for the “mother country,” which would in turn export finished goods back to the colonies.

The First Industrial Revolution began in the mid-18th century in Great Britain. It was a period in which technological advances were made, such as the spinning jenny and steam power. It was also when innovations in machine tools led to a shift from agriculture to large-scale cottage industries in weaving and textiles. The First Industrial Revolution also brought the development of railways, iron ships and manufacturing tools. Britain was the first country to experience this phase of industrialization, an experience that began later in Western Europe, the United States, and Japan. After mercantilism was ended by the British in the 1840s, British North Americans began to engage in activities that led to early industrialization.

Woman Using a Spinning Jenny

The Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves in the 18th century. The Spinning Jenny was a machine that allowed a person to spin several threads. Colourised black and white print, artist unknown.

(Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images)

First Industrial Revolution in British North America: 1780s to 1860s

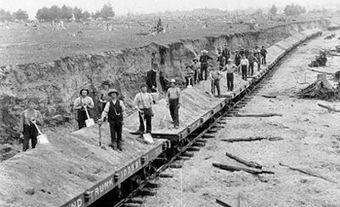

The shift from a largely agricultural and extractive economy to one that engaged in manufacturing was propelled by the shift from wind to steam power, and the embrace of new transportation technologies. In mid-19th-century British North America, early industry centred on the development of railways, which connected what is now Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime Provinces and eastern United States. Early industrialization was also shaped by the creation of canals, such as Montreal’s Lachine Canal (1820s), which facilitated the transportation of goods.

By the 1850s, some manufacturing, including small factories producing farm implements, tools and other metal goods, had developed in Montreal, Toronto and smaller centres. At the same time, advances in some sectors of the economy such as brewing, milling, textiles and shipbuilding reshaped economies and laid the basis for even greater industrialization. The early, petit bourgeois entrepreneurs of the First Industrial Revolution also reflected the growth of an emerging capitalist class, one that largely utilized small- to medium-sized family-run farms. Industrial investment in this period was often funded through British financing of bonds.

Second Industrial Revolution in Canada: 1860s to 1950s

The Second Industrial Revolution began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was marked by mass automation and the moving assembly line, large-scale factories and time management of workers. During this period, companies reshaped manufacturing, consumption, work and the urban landscape. The Second Industrial Revolution profoundly changed North America, especially the United States, where economies of scale — in the rail, steel, consumer goods and automotive sectors — transformed the economy. Along with further technological advances and developments in production processes, mass manufacturing came of age. In the automobile industry, entrepreneurs and industrialists such as Henry Ford revolutionized mass assembly by creating gigantic factories designed to turn out standardized, inexpensive and durable cars — a departure from the craft approach to manufacturing, which aimed to build luxury vehicles for wealthy customers. Mass production generated new markets for automobiles, and democratized both the production and consumption of cars.

This dynamic occurred in a host of sectors in the Canadian economy, from meat packing to farm implements to small-scale consumer goods to automobile manufacturing. Much of this industrial economic activity took place in Ontario and Quebec, where early industry had been established. Extraction of natural resources, particularly coal, forestry, oil and gas, and metals, fuelled these sectors, and also illustrated the broader impact of manufacturing upon non-urban communities. There was also significant development of the coal and steel industries in Nova Scotia, along with some shipbuilding.

After Confederation in 1867, manufacturing sectors of the economy were protected by tariffs outlined in the National Policy (1879). The policy intended to create and nurture industry in Canada by levying a tax of up to 20 per cent on goods made in other countries. While it protected some industries, the National Policy also facilitated the creation of “branch plants.” Factories owned by companies with headquarters in a different country, mostly the United States, branch plants were established in Canada in an effort to leap over the protectionist tariff wall. By the 1920s, American branch plant operations dominated in some industrial sectors in Canada, including automobile assembly, but also in consumer products, chemicals and auto parts. The National Policy also fueled regional grievances. The West and the Maritimes argued that the policy unfairly benefitted industrialists, workers, bankers and the population of Central Canada.

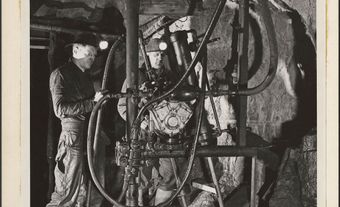

The First World War accelerated the Second Industrial Revolution in Canada. State efforts to support the war effort led to interventionist policies that pushed the manufacture of munitions and arms, transportation and other support equipment (see also Imperial Munitions Board).

Industrial wage economies drew immigrants and other Canadians to cities, where most industrial activity was centred (see Urbanization). During the Great Depression, the majority of Canada’s population became urban. The shift to a wage-dependent economy resulted in tremendous hardship during the depression. Mass layoffs in the industrial centres made many question the capitalist system, of which industrialization was such a large part.

The Second World War ended the Great Depression, in that it sparked a massive intervention in the industrial economy by federal state planners. Those state planners established new industries and crown corporations and directed private industry to produce machinery, transportation equipment and armaments and munitions for the war effort. For instance, Ottawa created the Polymer Corporation, a crown company, to produce rubber for the war effort, which helped revitalize the chemical industry in southwestern Ontario. In places such as Windsor, Oshawa and Ajax, leading manufacturers such as General Motors of Canada provided equipment and vehicles to the Canadian government under contract. The production of consumer goods was suspended for the duration of the war. Meanwhile, shipbuilding boomed on the East Coast, and steel production dominated in cities such as Hamilton, Ontario. By the war’s end, Canada had achieved full employment.

Impacts on the Workplace and Relations between Labour and Capital

The growth of mass manufacturing in the late 19th century reshaped work profoundly. By the time of the 1889 Report of the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada, it was clear that waged labour had become the key form of work for many Canadians. Yet the working conditions that they experienced and the wages they earned were, more often than not, less than ideal. Workplaces were dangerous, unsanitary and often cramped. Industrial accidents were common. Wages and hours were punishing, with child labour a common practice. Tobacco, textiles, heavy manufacturing and a host of other industries were part of an industrial system that exploited workers (see Working-Class History).

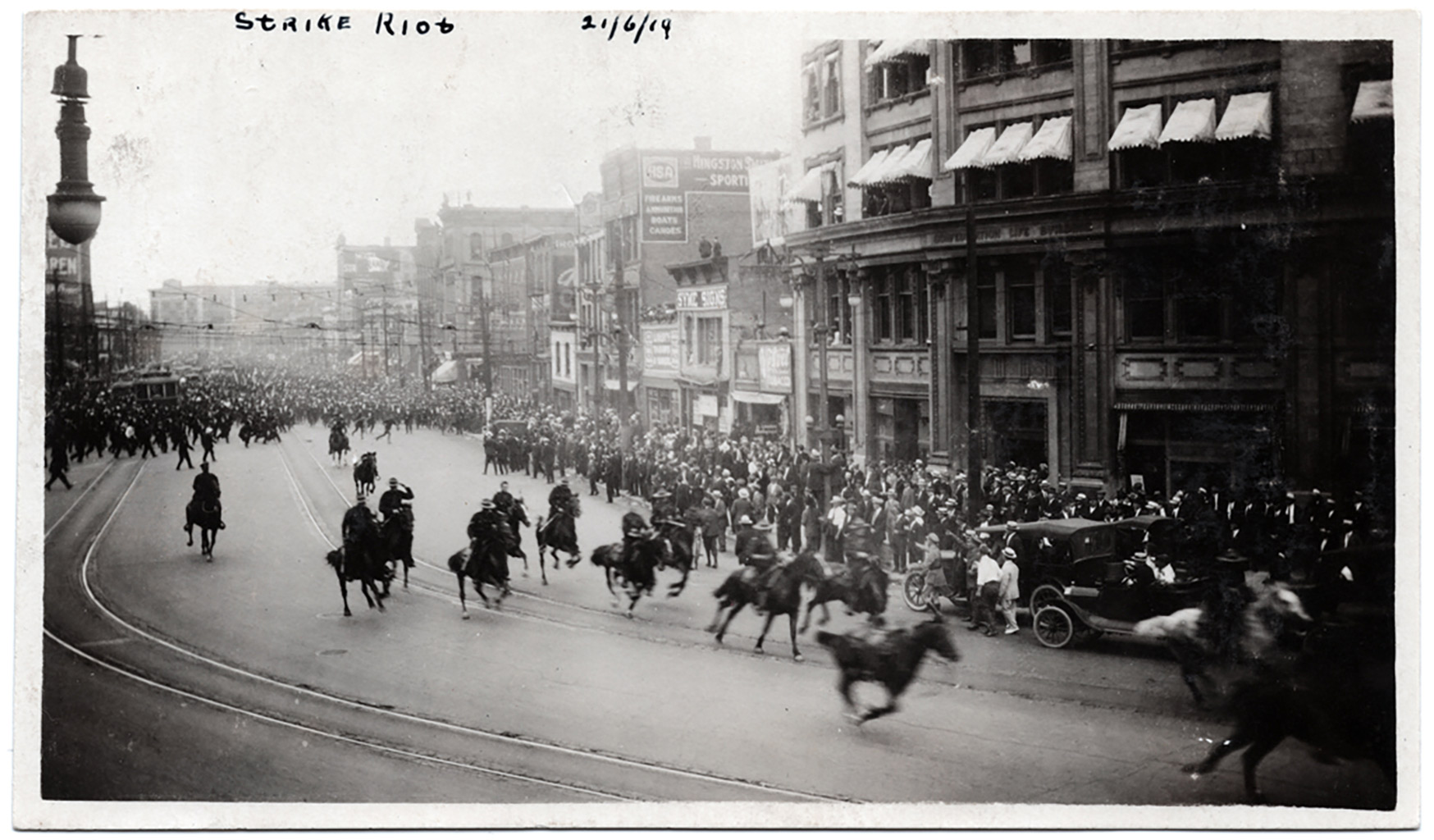

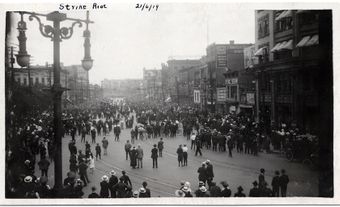

Organized labour emerged in the late-19th and early-20th centuries to challenge the exploitation of the working class. Differences within the labour movement — between craft and industrial unions — over who should be part of organized labour often fragmented these efforts. But unionization and the fight for better wages and working conditions continued. By the Winnipeg General Strike (1919), Canada faced a resurgent workers’ movement, one that was challenged by corporate interests and the government, who repressed workers’ organizations through the legal system (see Labour Organization).

During the Great Depression and the Second World War, the labour movement grew and challenged the capitalist system. Organizations such as the Canadian Congress of Labour and new unions such as the international United Auto Workers successfully organized industries and ensured recognition and rights for unions. They launched mass strikes and sit-down protests at workplaces across the country during the war. Changes in the legal system, such as the 1946 decision of Justice Ivan Rand to ensure union dues whether or not all employees were part of a union, also helped to facilitate the establishment of industrial unions in Canada (see Rand Formula). Industrial workers fought for collective bargaining, minimum wages, pensions, vacation pay, workplace benefits, legislated working hours, and legislation to protect against unemployment, workplace accidents and discriminatory hiring practices.

As early as the late 19th century, Canadian families had begun to shift from a farm-based economy to one based on industrial work and wages in urban areas. This required all family members to work for wages, either in factories (often fathers and children, but increasingly women, as well), or at home, where women took in boarders, cleaned and did piecework to stretch the family income. Wages — as opposed to subsistence farming or the selling of crops — became the primary form of work for Canadians, particularly after the 1920s. This reflected the profoundly class-based system of the industrial economy, which placed the means of production in the hands of a small group of wealthy elites.

Post-Industrial Age

In the 1950s, industrial work was at a peak in Canada. Cars, airplanes, steel, chemicals, appliances and other consumer goods were manufactured in Canada. Industrial labour constituted the largest segment of the male working population, one that was privileged by state policies that encouraged the male breadwinner ideal. By the 1960s and 1970s, approximately 30 per cent of the Canadian working population was in a union, often an industrial union. Major firms and manufacturing companies such as Massey-Ferguson, Bombardier, General Motors of Canada, the Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation and A.V. Roe Canada Limited dotted the industrial landscape.

Automated Robotic Welding Operation on an Assembly Line

The cabs of General Motors pick-up trucks move through an automated robotic welding operation on the assembly line at the Oshawa Truck Assembly Plant in Oshawa, Ontario, 26 October 2007.

(Photo by Norm Betts/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, automation, new production processes and productivity advances started to change the nature of industrial work, leading to greater dependence on technology and worker efficiency. At the same time, competition from newly industrialized or reindustrialized nations in Europe and Asia challenged Canadian manufacturers to remain competitive and to innovate. Starting in the 1960s, both in Canada and, more significantly, in the United States, deindustrialization began to occur, particularly in the industrial Midwest.

After the 1990s, deindustrialization became a significant factor in economic discourse, particularly in Ontario, where much of the industrial economy was located. Some of this deindustrialization was caused by trade agreements such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade/ World Trade Organization, and regional trade pacts such as the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (1989) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994) (see Canada and the World Trade Organization; Canada and NAFTA). Those trade deals effectively dismantled the protectionist approach of the National Policy. Meanwhile, automation, innovation and productivity increases meant that fewer workers were necessary to produce manufactured goods.

In the post-1973 period, following the Arab-led oil embargo that helped spur inflation and economic decline in much of the West, many durable goods and consumables were increasingly made outside of Canada, or North America. In the 2000s, auto assembly in Ontario faced restructuring and decline. The 1965 Auto Pact, a managed trade agreement that provided some guarantees for production in Canada, was found contrary to international trade rules, and the North American economy faced the financial crisis of 2008–09 (see Recession; Recession of 2008-09 in Canada).

By the 1970s, the computing revolution and digital technology had transformed the workplace. This impact was multifaceted. With an increasing amount of industrial work done by automation, including robotic processes, manufacturing work became less of a segment of the industrial economy. At the same time, computerization shifted much of the modern economy into the service sector, with retail, banking and finance, communications and other aspects of the economy outpacing manufacturing.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom