This entry is part of a series on the history of the newspaper industry in Canada. See also First Newspapers in Canada.

Independent and Partisan Newspapers: 1800s–1850s

The development of legislative assemblies in British North America encouraged the creation of political factions (see Party System). At the same time, particularly in Halifax, Saint John, Montréal, Kingston and York (Toronto), a merchant class with an interest both in reading commercial intelligence and in advertising was growing. Weekly newspapers sprouted up, allied with political movements and cultural groups, as well as various mercantile and agricultural interests. At the same time, cheaper and more efficient presses brought more printers into the business. Many of the newspapers established during this period were run by independent “printer-editors” who controlled both the press itself and the editorial message of their publications. To make money, they published almanacs, books and pamphlets for various clients. As reader appetites for news increased, newspapers proliferated. During this period, some cities and towns were covered by two newspapers, including Kingston, York, Montréal and Québec City.

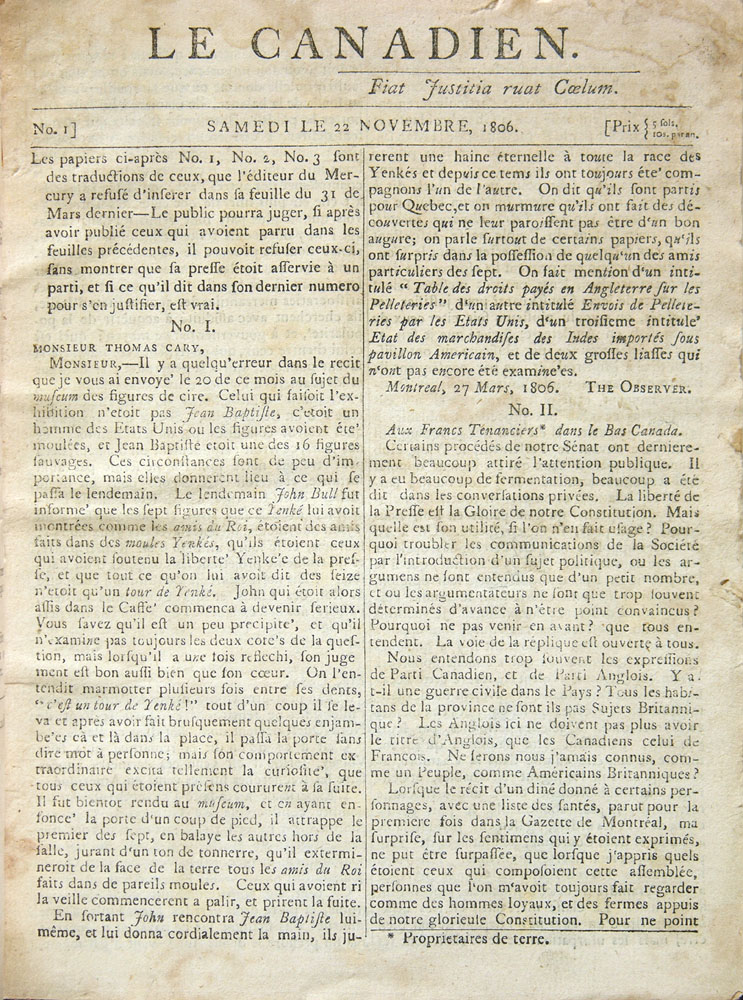

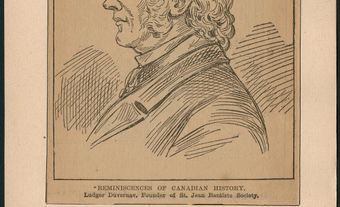

In Lower Canada, the Quebec Mercury (established in Québec City in 1805) and the Montreal Herald (1811) became mouthpieces for the province’s English-speaking merchants and politicians, while French-language newspapers Le Canadien (established in Québec City 1806) and La Minerve (Montréal, 1826) spoke for the rising French Canadian professional and political interests.

Printer-editor William Lyon Mackenzie published the first edition of the Colonial Advocate on 18 May 1824 in Queenston, Upper Canada. He established the weekly in order to argue the cause of the Reform movement in general and farmers in particular against the dominant professional and mercantile groups in Upper Canada (see Family Compact).

In the Maritimes, newspapers such as the Novascotian (established 1824) also challenged the authority of colonial oligarchies — especially under the editorship of political reformer Joseph Howe, a leading proponent of responsible government (see Joseph Howe: Tribune of Nova Scotia).

Amor de Cosmos used his newspaper, The British Colonist, first published on 11 December 1858, to promote responsible government and British Columbia’s entry into Confederation. As was the case with Mackenzie and Howe, work in newspapers helped launch de Cosmos’s political career.

Multicultural Newspapers: 1850s–1910s

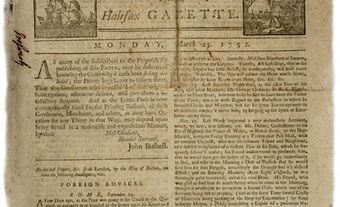

The first newspaper in Canada published in neither English nor French was the German-language Halifax weekly Die Welt, und Neuschottländische Correspondenz, first printed in January 1788. As printing presses and materials became more affordable, more printers were able to establish independent printing houses. A number of these presses published newspapers that reflected the needs, interests, politics and languages of specific communities.

Voice of the Fugitive

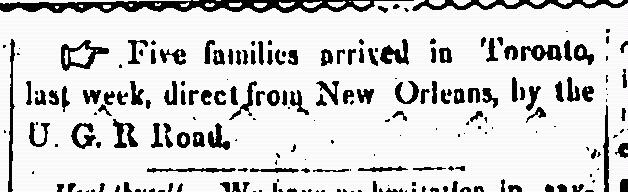

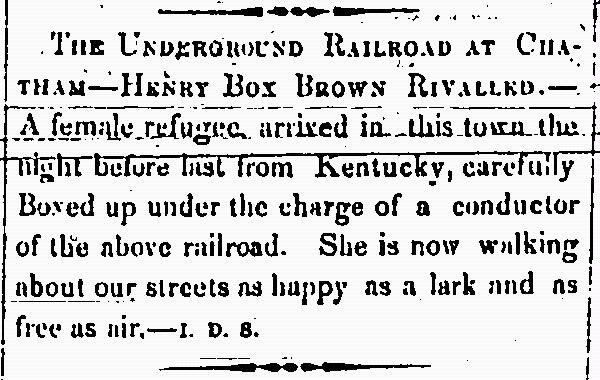

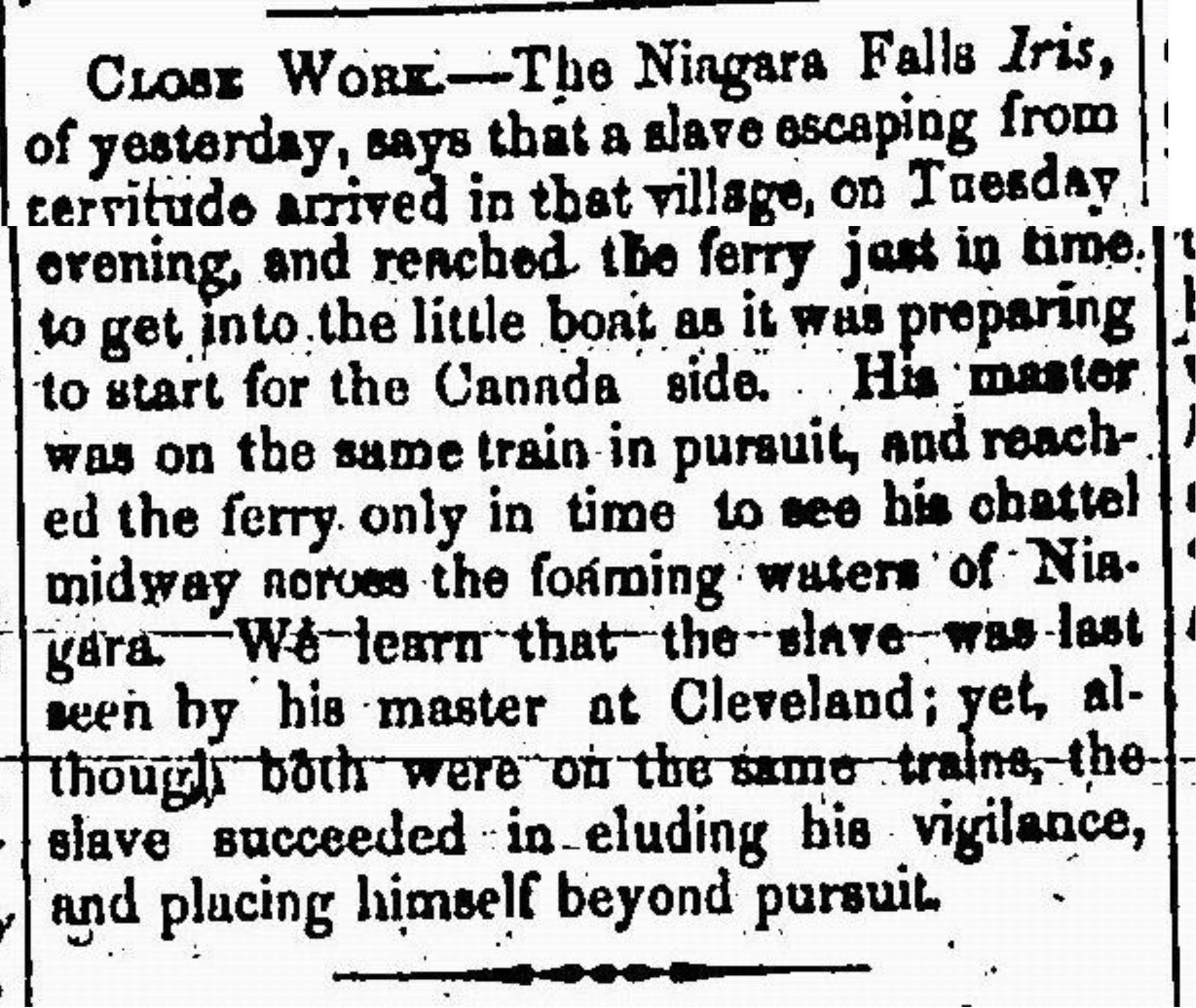

On 1 January 1851, Henry and Mary Bibb published the first edition of The Voice of the Fugitive, the first Black-owned newspaper in Canada. Published from Sandwich, Canada West (now Windsor, Ontario), the paper was used to communicate with supporters of the Underground Railroad. Its subscribers were located in both Canada and the United States, and the paper provided useful information for Black people settling in Canada.

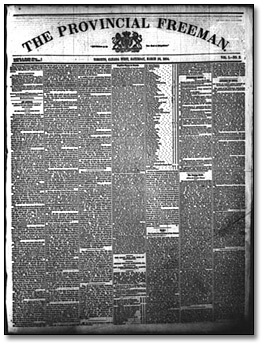

The Provincial Freeman

When the first edition of The Provincial Freeman was printed in Sandwich, Canada West on 24 March 1853, Mary Ann Shadd became the first Black woman in North America to publish and edit a newspaper and one of the first female journalists in Canada. Aware that readers may disapprove of a female editor, the newspaper’s first edition named Samuel Ringgold Ward as editor and Alexander McArthur as corresponding editor. The Provincial Freeman, however, was Shadd’s initiative. Under her direction the newspaper was committed to anti-slavery and advocated for African Americans to emigrate to Canada West. The newspaper also highlighted the successes of Black persons living in Canada and included news of formerly enslaved Africans Americans arriving there. Published until 1860, The Provincial Freeman’s motto was “Self-reliance is the true road to independence.”

Das Berliner Journal

First published in 1859, Das Berliner Journal was a German-language weekly published in Berlin, Canada West (now Kitchener). The paper merged with or acquired four other papers between 1904 and 1909 and was a source of foreign and domestic news as well as advice for new and settled German Canadians. It was the last German-language newspaper in Ontario before a federal order-in-council banned the publication of German newspapers in 1918 (see First World War).

Tairiku Nippō

Tairiku Nippō (Continental Daily News) was a Japanese Canadian newspaper published in Vancouver from 1907 to 1941. Most items were written in Japanese and covered a range of subjects relevant to Japanese immigrants in British Columbia. In 1941, the federal government shut down Japanese-language newspapers (see Internment of Japanese Canadians).

The Chinese Times

The Chinese Times was a daily paper first published in Vancouver in 1914. The longest-running Chinese community newspaper in Canada (1914–1992), its coverage was local and foreign.

Newspapers, Politics and the State: 1850s–1900s

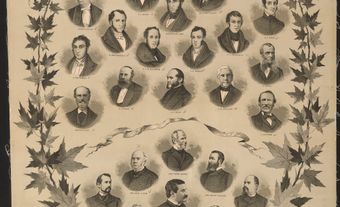

By the early decades of the 19th century, most major newspapers were allied with either the Reform movement (now the Liberal Party) or the Conservative Party. These papers were by no means simple tools of the parties they claimed to support but more organs of specific leaders or factions within those parties. Thus, the Globe (established in 1844) was a personal organ of its publisher, the Reform politician George Brown. The Toronto Mail (1872), though set as an outlet for the Conservative Party, was quickly captured by the dominant faction of the party led by Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald.

The Manitoba Free Press, founded by W.F. Luxton in 1872, displayed a distinct Liberal preference from its earliest days. It was purchased in 1898 by Clifford Sifton, a prominent Liberal politician and Cabinet minister, and thereafter was the organ of the Liberal Party on the Prairies.

It was not unusual for an organ to deviate from the party line. The Toronto Mail, for example, broke with the Macdonald Conservatives in the 1880s, forcing the party to set up the Empire in 1887. The relative independence of newspapers from political parties and governments varied from place to place. But in general, newspapers had more potential for independence from parties as their revenues from circulation and advertising grew.

While they may not have been tools of the parties, newspapers remained closely tied to political factions well into the 20th century. The Toronto Star, established by striking printers with trade union backing in 1892, was reorganized in 1899 by a business consortium anxious to obtain an organ for the new Liberal prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier. During the first decade of the 20th century, the Calgary Herald used the organizational apparatus of the Alberta Conservative Party to sell subscriptions. As late as the 1930s, most major Québec newspapers were tied into patronage from the ruling government.

In part, the politicization of newspapers continued because readers demanded partisanship. Politics was a serious matter in 19th century Canada, and newspapers were expected to have views. Thus began the phenomenon of the two-newspaper town. By 1870, every town large enough to support one newspaper supported two — typically, one Liberal and one Conservative. Furthermore, newspapers never cut themselves off completely from government patronage. From 1867, the federal government subsidized newspaper publishers by granting them special postal rates (see Postal System). Canada’s first international wire service, Canadian Associated Press (1903), was subsidized by the federal government, as was the domestic news co-operative, Canadian Press, during the initial years after its founding in 1917.

The relationship between Canadian newspapers and the state has also had a darker side. Early publishers who were considered overly critical of government actions could and did find themselves in jail (see Joseph Howe: Tribune of Nova Scotia), and libel laws were used to silence bothersome editors (see Law and the Press). In the 20th century, state action was aimed primarily at left-wing newspapers. The Communist Party of Canada found itself proscribed and its publications banned at various times. The Québec government of Maurice Duplessis (1936–39 and 1944–59) used its Padlock Act to shut down what it considered to be communist newspapers. Limited censorship was imposed by the federal government in 1970 following the kidnapping of two men during the October Crisis.

Change in Revenue: The Rise of Advertising

While partisanship remained, the financial dependence of newspapers on governments and political parties declined throughout the 19th century. The reason was related to the economics of newspaper publishing and to overall economic development. Newspapers faced high overhead costs, i.e., newspapers were forced to incur the same initial outlays for equipment, typesetting and editorial matter whether they printed one copy or a run of 10,000. In the 1860s, when daily circulations were usually under 5,000, these overhead costs were covered by political party patronage. But as population expanded and literacy increased, publishers were able to spread these overhead costs over more readers. In addition, as a newspaper’s circulation increased, merchants became more interested in it as an advertising medium. With productive capacity increasing in all industries, advertising, as a means of persuading people to buy the massive volume of goods being produced, became crucial (see Industrialization in Canada).

Early advertisers were wholesalers trying to catch the attention of other merchants. But by the 1890s, retail advertising, aimed at a mass market, was dominant, and big-city dailies earned just a third of their revenues from subscribers and single-copy sales. By 1900, consumers were flooded with newspaper advertisements enticing them to purchase such things as soap, patent medicines or electric belts.

Technological Developments

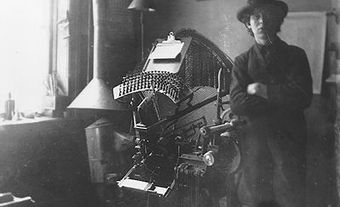

Technological developments in the newspaper industry hastened the trend to large-circulation, advertising-based newspapers. The spread of the telegraph during the 1850s and the laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866 boosted access to world news but at the same time increased newspapers’ production costs. By the 1880s, high-speed rotary (or web) presses, which printed on rolls of paper, and stereotyping allowed newspapers to expand their circulations in order to earn more revenue to cover these costs.

DID YOU KNOW?

A stereotype is a type of printing plate that duplicates entire pages of a newspaper, including both type and illustrations. The more common use of the term, meaning an oversimplified impression of a person or group of people, is a metaphor of the printing term.Typecasting is a mechanical printing process in which individual letters are cast in a mould and arranged to form words, sentences and paragraphs. The term is also used to describe a person who is considered to fit a stereotype, or an actor who is repeatedly assigned roles as the same type of person.

In 1876, the combined circulation of daily newspapers in the nine major urban centres was 113,000. Seven years later, it had more than doubled. Railway building, from the mid-19th century onward, put more of the population within reach of daily and weekly newspapers. By the 1890s, typecasting machines such as the linotype allowed daily newspapers to expand their size from the standard 4-, 8- or 12-page format to 32 or 48 pages (see Print Industry). This greatly increased the amount of advertising space available. At the same time, the development of newsprint manufactured from wood pulp provided a cheap source of supply to newspapers (see Pulp and Paper Industry). The price of newsprint plummeted from $203 per ton in 1873 to $50 per ton in 1900.

DID YOU KNOW?

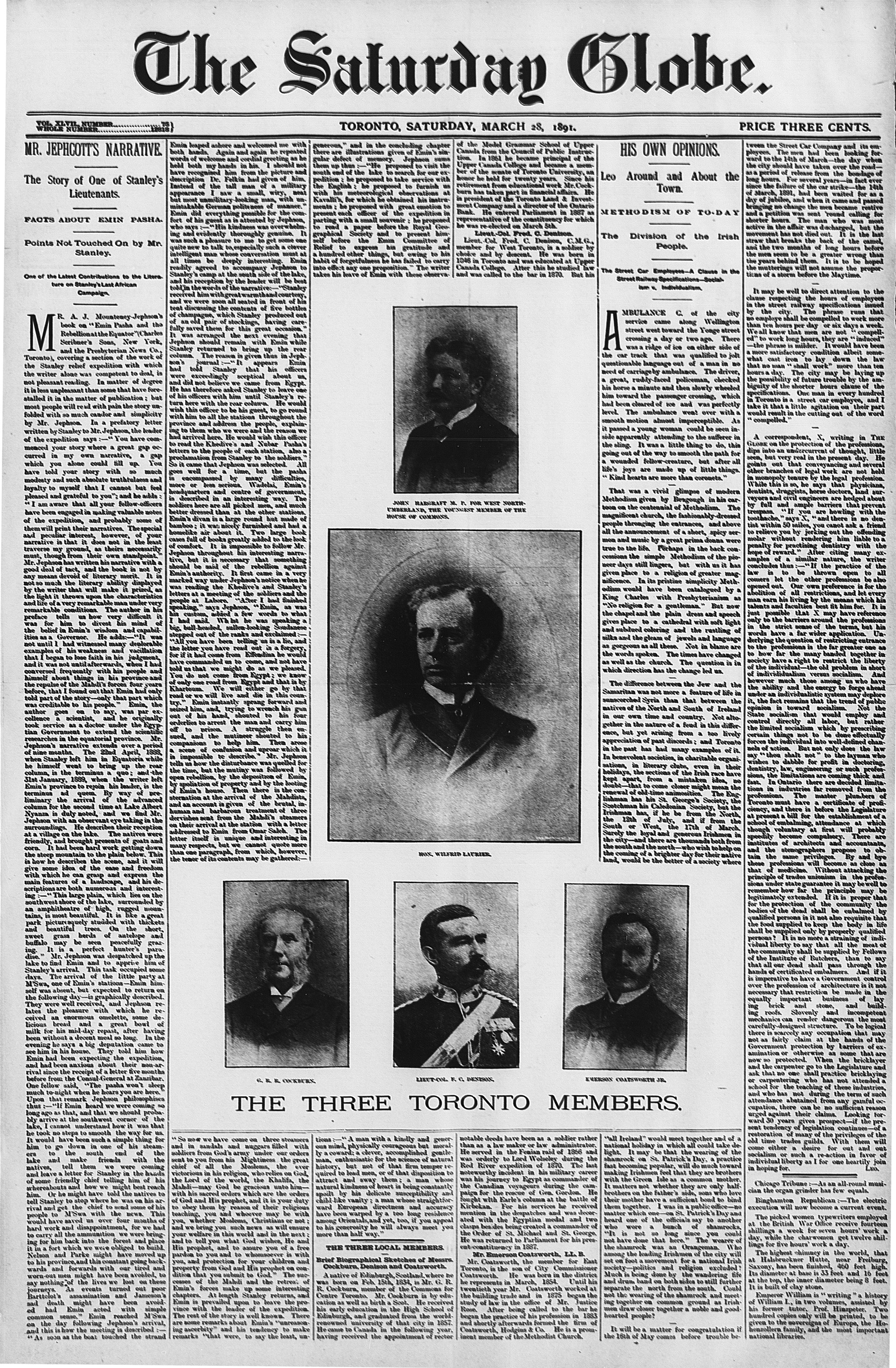

The first photograph published in Canadian daily newspapers was a halftone photo engraving of Liberal Party leader Wilfrid Laurier in the Saturday Globe on 28 March 1891. However, photographs were difficult and expensive to reproduce in newsprint and were therefore seen rarely and only in major dailies. They did not become a commonplace feature in Canadian newspapers for some time.

Westward Expansion

Newspapers, first weeklies and later dailies, sprang up in the West as settlement increased there (see History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies). The first newspaper in the West was the French-language weekly Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Calédonie. Journal politique et lit[t]éraire. Organ des populations françaises dans les possessions anglaises, published in Victoria in early 1858. Though it lasted only two issues, its printer used the same press to print The British Colonist, which began publication on 11 December 1858. The paper was edited by Amor de Cosmos.

The first newspaper in what is now Manitoba was the Nor’-Wester, first published on 28 December 1859 in Red River. The Nor’-Wester was shut down during the Red River Resistance in 1869, when its press was taken over by Louis Riel and the Métis provisional government, who used it to print the short-lived New Nation.

The Manitoba Free Press (see Winnipeg Free Press) began publication on 30 November 1872. As its publishers explained, the weekly was printed on “the first power printing press ever brought northwest of St. Paul, [Minnesota].”

The first newspaper published in the vast expanse between Red River and Victoria was the Saskatchewan Herald, first printed on 25 August 1878 in Battleford. The Edmonton Bulletin printed its first edition on 13 December 1880, the first newspaper in what is now Alberta.

The first papers in Yukon were printed in Dawson during the Klondike gold rush, including the Klondike Nugget, first published on 27 May 1898, and the Yukon Midnight Sun, 11 June 1898.

Daily Newspapers and Evening Editions

Early newspapers were predominantly weeklies, although a few might be published two or three times a week. Canada’s first daily newspaper, the Montréal Daily Advertiser, began publishing on 14 May 1833, only to go bankrupt within a year. Daily publication began in earnest in the 1840s, when two other Montréal newspapers, the Montreal Gazette and Herald, decided to publish each day during the busy commercial summer season. Population growth, increased literacy and urbanization hastened the transformation from weekly to daily journalism. In 1873, there were 47 dailies in Canada; by 1900, the country boasted 112.

Use of the telegraph increased the speed with which information travelled, while technological advancements in print allowed for faster printing during the second half of the 19th century. This increased competition among papers to print breaking news first. Depending on the time of the event, news could either be printed in the morning or evening edition of a paper, and many papers added second editions to their publishing schedule in order to compete — often at a discount rate. Both the Globe and the Mail added evening and morning editions, for example. Some publishers gave their second papers other names, as was the case with the evening edition of the Halifax Herald, called the Mail, and the evening edition of the Chronicle, called the Echo.

The major dailies, in turn, used the mail and the railway systems to blanket the countryside with their weekly editions and, by the 20th century, with special weekend supplements such as the Toronto Star Weekly or Montréal Family Herald.

The growth of a new working class in the larger cities, particularly Toronto and Montréal, encouraged new kinds of newspapers with more emphasis on local news, mass circulation, classified advertisements and muckraking (i.e., searching for and revealing scandal, especially about well-known people). These newer papers, which sold for 1¢ a copy (one half or one third of the price of the older, established dailies), included Montréal’s La Presse (established 1884) and Star (1869); Toronto’s Telegram (1876), News (1881), World (1880) and Star (1892); and the Hamilton Herald (1889). The older, established papers also increased circulation to attract new classes of readers. In Toronto in 1872, each family bought, on average, one newspaper; by 1883, the average Toronto family purchased two newspapers each day.

However, in the province of Québec as a whole, newspaper growth was initially hampered by a low literacy rate. In 1871, only 50 per cent of Québec’s French-speaking adults could read and write, compared to 90 per cent for all Ontario adults. Unique to Québec though were daily newspapers devoted to religious ends, such as the ultramontane Roman Catholic Le Nouveau Monde (1867) and the Protestant Daily Witness (1860). In Québec, newspapers allied to the church, to nationalism and to the cause of French Canada flourished well into the 20th century. In 1910, nationalist Henri Bourassa founded Le Devoir to promote Québec interests. Papers such as Le Devoir, though small in terms of circulation, remained influential among the Québec intelligentsia (see French Canadian Nationalism).

Women and the Press

The Globe was the first paper to include a women’s page in 1882, a section most famously edited by Kathleen “Kit” Coleman. Other papers ran material aimed at women, including the Montréal Herald, while others ran columns by female columnists such as Robertine Barry (writing as Françoise in La Patrie) and Emily Murphy (writing as Janey Canuck in a number of major papers).

Though fewer than 60 women were identified as journalists in the 1901 census, women journalists were on the ascendancy. Advertisers had learned the value of what is now called “adjacency” — ads for goods and services placed next to columns and stories written by female writers and of interest to women readers, who made most household purchasing decisions.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom