The Carignan-Salières Regiment was a regiment of French troops who were sent to New France from 1665 to 1667 to fight the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois). These professional soldiers, who had little experience with fighting in the woods, invaded the lands of the Haudenosaunee but did not succeed in defeating them. Nevertheless, the French show of force led to a peace accord in 1667. Though most of the French soldiers then went home, some stayed, married and settled in New France. Many of them married Filles du Roy and now have many descendants. Quebec municipalities such as Berthier, Chambly and Verchères still bear the names of officers of this regiment.

Original by L. Rousselot, 1931.

Professional Army

In the late 1640s, the incursions of the Haudenosaunee in Canada were so frequent that a state of almost continuous warfare reigned in New France. Settlers were attacked as soon as they ventured beyond city walls, especially at Ville-Marie, which was particularly exposed. The colony lacked soldiers to counter this threat. To stabilize the situation, King Louis XIV “resolved to bring the war right into their homes to exterminate them entirely”. He decided to send to New France an entire regiment that embodied the latest military reforms: the Carignan-Salières Regiment.

This regiment had been formed in 1659 by the merger of two foreign regiments then in the service of France: the regiment of Thomas-François de Savoie, Prince of Carignan, and the former regiment of the German Johann Balthasar de Gachéo, then commanded by Henri de Chastelard de Salières. Having received orders to mobilize, the regiment, some 1100 soldiers strong, left Lorraine in January 1665 and marched across France to La Rochelle, where it embarked for Canada. The first contingent arrived at Quebec City in June of that year, and the last in September. The regiment was placed under the command of Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, lieutenant-general of the West Indies and New France, who arrived in late June with 200 more soldiers.

These soldiers’ arrival was impressive: nearly 1300 men, marching under enormous regimental flags to the beat of drums, disembarked into a colony of just 3215 souls. It was the first time that soldiers from the French royal army had been sent to Canada. Dressed in brown coats with white and grey trim and black hats decorated with black and chamois ribbons, these soldiers were equipped with modern weapons, the result of recent military reforms in Europe.

Most of the soldiers had muskets, which were charged with black powder that was ignited with a burning match. These weapons were powerful but hard to handle. The troop was also equipped with 200 flintlock muskets and 100 flintlock pistols, which was unusual at the time. These were modern weapons, in which the black powder was ignited by a spark produced by the impact of a flint on a piece of tempered steel. Flintlock muskets could be loaded faster and, most important, were far safer. They were also equipped with bayonets, a kind of long knife mounted on the muzzle, for hand-to-hand combat.

Show of Force

As soon as the soldiers arrived, they went to work. There was no road network in New France at the time, so travel was mainly by canoe, and the Richelieu River was then one of the most frequently used invasion routes, nicknamed the “river of the Iroquois”. The men of the Carignan-Salières therefore built forts along this river to block access to the St. Lawrence Valley. By the fall of 1665, Fort Saint Louis, Fort Richelieu and Fort Sainte-Thérèse had been completed, and the French mounted a bold plan to bring the war to the heart of enemy territory in the dead of winter.

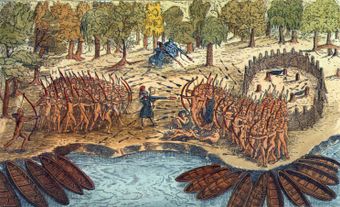

In January 1666, nearly 600 French soldiers and 70 Canadian militiamen invaded the lands of the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk). But the French commander refused to wait for the Algonquin guides who were supposed to lead his troops through the woods, and they became lost. With no snowshoes, the soldiers sank into the snow, 60 of them died, and the expedition failed. In September, another attempt was organized. This time, the soldiers fulfilled their mission. They burst into the Haudenosaunee villages and burned their longhouses and their harvests. The operation’s success had been ensured by a feat of logistics: the construction of a fleet of 152 flatboats and a few rowboats had enabled this small army to move efficiently. The victory seemed total, but no combat had actually taken place: the Indigenous defenders had preferred to retreat as the French advanced.

In conclusion, the soldiers were ill prepared for their military campaign in Canada. In the winter of 1666, when the men slept outside, they had only one blanket for every three of them. Those who spent the winter of 1667 at Fort Sainte-Anne suffered cruelly from the cold and malnutrition. Though there had not been any real fighting, the Haudenosaunee were impressed enough by this show of force to sign a peace treaty with the French in 1667. The destruction together with the famine had forced the Kanyen’kehá:ka to sign the treaty that had already been signed by four of the five Haudenosaunee nations: the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca.

Legacy in Canada

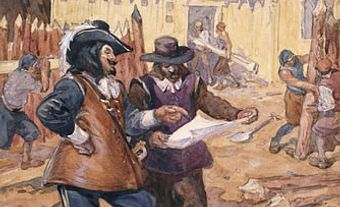

Once peace had been negotiated, the colony could begin to grow. Settlers no longer had to fear that an enemy would burst out of the woods to attack their homes. Their mission accomplished, the soldiers of the regiment were called back to France in 1668. But King Louis XIV, supported by his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, offered attractive conditions to any officer who wished to stay in Canada: a seigneurie (see Seigneurial System), a year’s worth of provisions and a sum of money that depended on the officer’s rank. To soldiers willing to stay, the king also granted a piece of land, a year’s provisions and 100 Tournois pounds — the equivalent of a year’s salary. The idea was to enable men with combat training to contribute both to the settlement of New France and to its defence.

About 400 men decided to stay, of whom 283 married. Very often, soldiers settled on the land that had been granted to their captain as a seigneurie. Many married Filles du Roi and now have numerous descendants. Most of the seigneuries granted to officers of this regiment were located on the St. Lawrence River at the mouth of the Richelieu. Berthier, Lanoraie, Lavaltrie, Sorel, Contrecoeur and Verchères, for example, still bear the names of these officers.

The arrival of these soldiers allowed other colonists to settle in the newly secured areas and to extend colonization toward the mouth of the St. Lawrence and the Gaspé Peninsula. Finally this new peace marked the start of a period of prosperity and growth in New France that lasted for nearly 20 years.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom